We would like to thank Barbara Fast and Spencer Myer for this insightful interview on practice. Want to learn more about practicing? Register for the free webinar, “#100daysofpractice: Selection and adaptation of self-regulated learning strategies in an online music performance challenge” presented by Camilla dos Santos Silva and Helena Marinho, hosted by Alejandro Cremaschi on November 29. Learn more and register here: https://pianoinspires.com/webinar/11-29-23-webinar/.

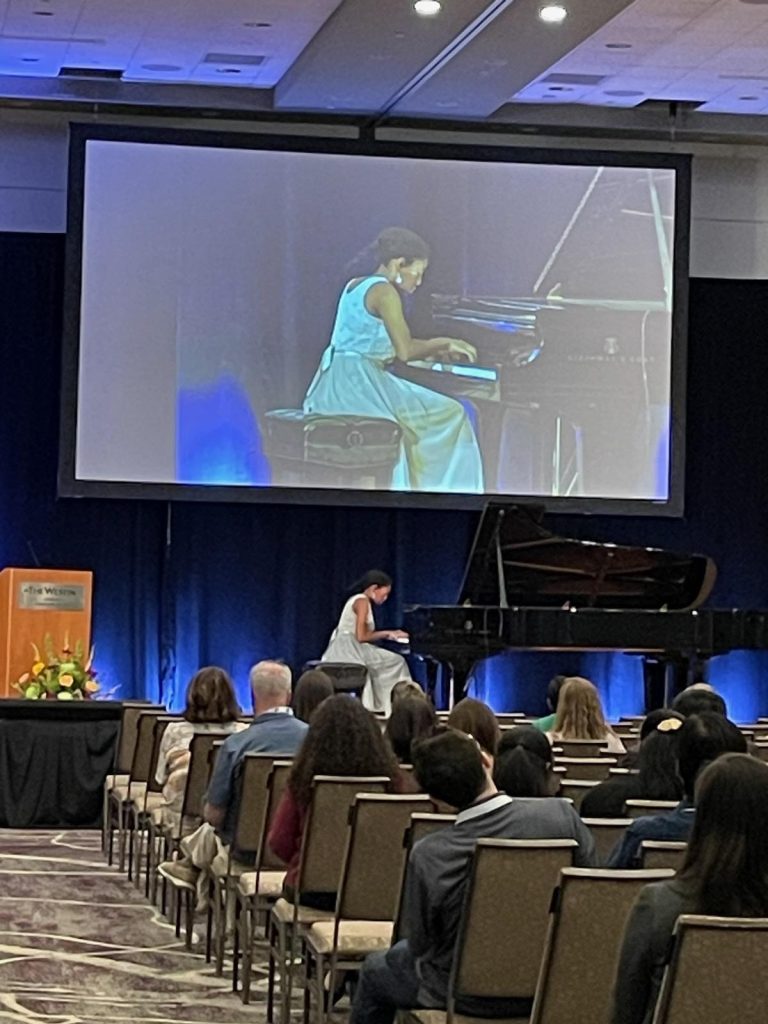

I attended Spencer Myer’s practicing workshop at the NCKP 2019 Conference. His emphasis on engaging the brain in variable practice techniques sparked my interest and supports research on how we learn. I thought I knew every possible practice suggestion, but Spencer presented and demonstrated many new and unusual ideas that he was using in practicing and teaching. I found myself using the notes I had taken for my own practicing workshops and classes, and knew I needed a concrete way to share his tips with other musicians. I interviewed Spencer Myer on February 2, 2020, as a way to share his thoughts on practicing with piano teachers throughout the world. The article is the essence of our interview together.

Barbara Fast: What prompted your interest in the topic of practicing?

Spencer Myer: I discovered the practice techniques that I’ll be discussing during the period of my life when I was entering competitions. I was practicing with the intent of complete cleanliness and solidity. I thought, “how am I going to get to the point where I can walk on stage and not be afraid of having a memory slip?” I started to explore what seemed at a time to be different, crazy, and random practice techniques.

BF: What are your foundational ideas about practicing for performance?

SM: I feel that our memory is made up of 80% muscle memory and 20% other memory. Of course, playing an instrument is physical, so muscle memory has to be part of the equation. We are all human; memory slips happen for everyone, and relying on muscle memory from hours of repetition can be an aid to get through a memory slip. But strengthening our brain, getting away from relying only on muscle memory, that other 20%, is where we find the mental solidity that we’re going for in a performance.

BF: Strengthening the brain: how does that help you go beyond muscle memory?

SM: The point about muscle memory is that studies have shown it’s impossible for our brains to multitask; we can’t think about two things at once. Removing muscle memory, taking it away in our practice, increases the brain’s involvement in our memory. The idea is how to make the passage feel different or foreign to our body so that our brain is forced to engage.

BF: What’s your first practice tip for changing physical sensation in the body?

SM: The most obvious example for changing physical sensation is slow practice. It’s a useful tool for drilling and refining minor muscle motions that we are required to use with great speed in performance. Slow practice is often viewed as a tedious or brainless exercise that our teachers tell us to do. Actually, it really engages the brain, because it deviates from the repetition we are so used to. Practicing the music in a way that feels physically different—slowly, or with inconsistent tempos—that is the key.

BF: Practicing with inconsistent tempo – that’s an unusual idea.

SM: Inconsistent tempo is something that I often utilize in practice. It’s similar to slow practice because inconsistency forces the brain to think about every next note more consciously. Changing tempo also allows us to practice in a much more improvisatory way. It’s much more fun and propels exploration of phrasing and musical intent, which further engages the brain.

BF: Do you also use alternating rhythm practice?

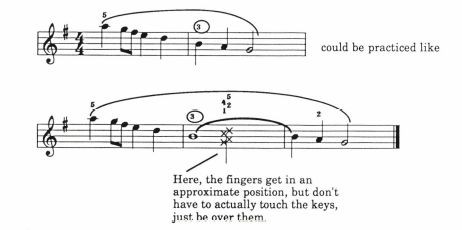

SM: Alternating rhythms is something we tell our students to do and it can often be mindless. But, I think it’s a great exercise for the brain because it’s a huge changeup. For me it works best with challenging sections, such as scales and arpeggios in the repertoire. The basic idea is utilizing dotted rhythms, and their reverse, in place of even rhythms. Triplets and groups of four notes can also be performed, with length added to any chosen note of each group. These alternating rhythms can be random or much more regular. But again, it’s the extreme change in physicality that engages our brain that is important.

If you enjoyed this excerpt from Barbara Fast and Spencer Myer’s interview “Engaging the Brain: Practice Tips from an Interview with Spencer Myer,” you can read more here: https://pianoinspires.com/article/engaging-the-brain-practice-tips-from-an-interview-with-spencer-myer/.

MORE ON PRACTICING

- WEBINAR ARCHIVE: Let’s Talk About Practicing with Barbara Fast and Spencer Myer

- WEBINAR ARCHIVE: Practicing and the Brain with Barbara Fast and Molly Gebrian

- WEBINAR ARCHIVE: Practicing Piano through the Early Stages with Sara Ernst

- ARTICLE: The “How-Tos” of Practicing by Joanne Haroutounian

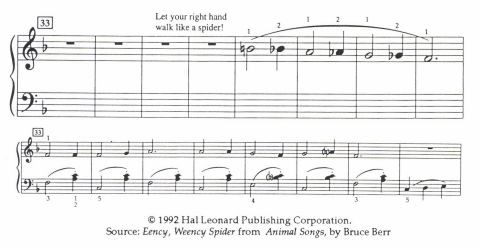

- ARTICLE: The Art of Practicing: I Really Should Be Practicing Well by Bruce Berr

- ARTICLE: The Art of Practicing: Broad Principles by Scott McBride Smith

- ARTICLE: Productive Practicing: The Hidden Part of the Icebergby Peter Jancewicz

- ARTICLE: Practicing Alongside Our Intermediate Students by Sara Ernst

- And many more! Use our search feature to discover more resources on practicing.

Not yet a subscriber? Join for only $7.99/mo or $36/yr.

Barbara Fast is Piano Chair and Director of Piano Pedagogy, coordinates the group piano program and teaches graduate piano pedagogy at the University of Oklahoma. An active workshop clinician, she co-founded the Group Piano/Piano Pedagogy (GP3) Forum. She is the co-author of iPractice: Technology in the 21st Century Music Practice Room.