We believe passionately that piano teachers change the world through their dedication to students and communities. Our Power of a Piano Teacher campaign shares personal tributes to document the extraordinary contributions of piano teachers. We welcome you to celebrate your teacher and share your tribute with us by making a donation to the Frances Clark Center. Together, we will further amplify the meaningful work of our noble profession.

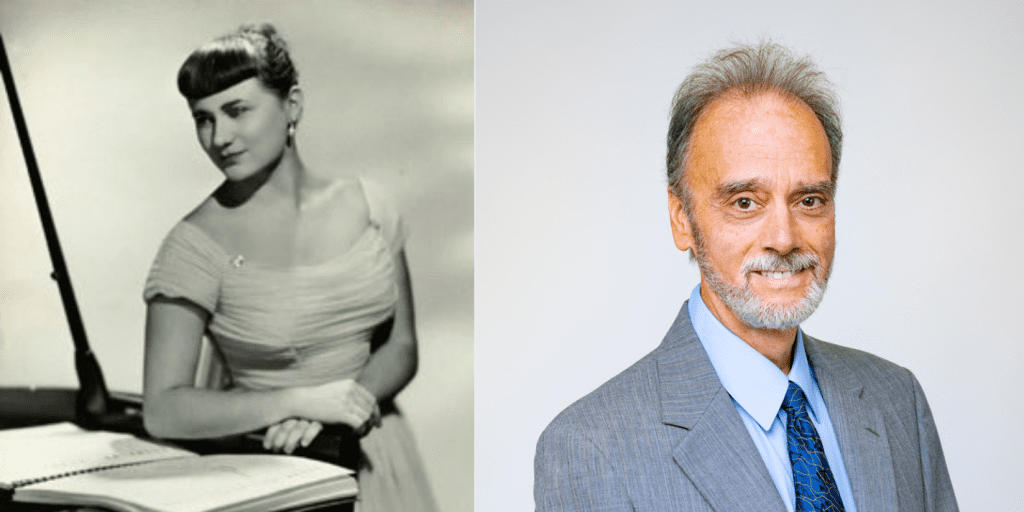

Lessons with Claudette Sorel (1932–1999) exposed me to remarkable musical insights, communication skills, and a world-class perspective, which continue to nurture and inform my own teaching and performing career.

Little did I know of her background when I walked into her studio in September of 1968. Imagine my feelings of awe when I discovered her history: a child prodigy who made her recital debut at the age of 11 at New York’s historic Town Hall in 1943. The New York Times reviewer remarked, “A child capable of so polished and eloquent an example of pianism has a future worth watching.” Her scholastic honors included completing high school in three years as valedictorian and simultaneously attending The Juilliard School on full fellowship, from which she graduated with highest honors and as its youngest graduate. At the Curtis Institute of Music, she received an Artist Diploma with highest honors. This was accomplished while she was also a student at Columbia University, from which she received a degree in Mathematics, Cum Laude.

During her career Ms. Sorel made more than 2,000 concert, recital, and festival appearances and appeared as soloist with 200 orchestras, including the New York Philharmonic, Boston Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, NBC Symphony, and London Philharmonic. Her signature work was Edward MacDowell’s Piano Concerto No. 2, and she gave world premieres of music by Lukas Foss, Harold Morris, Paul Creston, and Peter Mennin, among others.

Her dedication to the Arts, especially to promoting the participation and recognition of Women pianists, was always a primary goal of hers, as strongly announced in an article for Music Journal, March 1968 entitled “Equal Opportunity for Women Pianists.” Her advocacy continues to this day: The Elizabeth & Michel Sorel Charitable Organization Inc. is a 501©(3) private foundation, established in 1996 by Claudette Sorel and named for her parents. The mission of The Sorel Organization (www.SorelMusic.org) is to expand opportunities and stretch the boundaries for women musicians in the fields of conducting, composition, film scoring, performance, arts leadership, education, and scholarship.

She was my teacher for my four undergraduate years at SUNY Fredonia, where she taught for many years. While chairing the piano department in the 1970s, she became the first woman in the entire New York State University system of over 30,000 faculty to be named Distinguished University Professor.

My memory of my first lesson is as vivid today as it was that fateful day in the Fall of 1968: she asked me to perform a piece, so I chose Chopin’s Polonaise in A Major, Op. 40, No. 1. I was very confident of my abilities to perform this piece well and dove in with all the gusto that youthful ignorance can provide. Upon completion, she looked at me and quietly uttered, “Well, now we’ll learn how to play the piano.” I was devastated, surprised, angry, confused. I was already really good, wasn’t I?

She then demonstrated several things to practice (how I wish I could remember those exact ideas!) and I reluctantly went to a practice room to try them out. To my utter amazement, they worked! Immediately! Her magic continued unabated for four years and actually, to this day. She encouraged my burgeoning interest in jazz piano and gave me exercises that proved invaluable to my jazz playing! How did she know to do that?! She enjoyed (or was certainly amused by) my preliminary endeavors at multimedia concerts, using Kodak slides in a tray, overhead transparencies, and Fender Rhodes Electronic Keyboards.

She would frequently conduct workshops for piano teachers in the Buffalo area and would bring one student from each year to demonstrate her approach to technique. That first year, I was the freshman representative. I played some scales and arpeggios. Then a sophomore played, followed by a junior and then a senior. We could all hear the progression of clarity, focus, sound, etc. Each of her students would speak to the teachers; we in turn learned how to “work the room,” how to address questions, and how to help teachers (and ourselves) learn.

I hear her voice strongly advocating underrepresented composers, advancing gender and racial equality in classical music, and expanding the classical music canon for future generations.

Presently, in private lessons, I find myself hearing her voice guiding me, prompting me to ask my student a particularly astute question in order to facilitate the learning. Her knowledge of the physical world of producing a relaxed and powerful playing mechanism has stayed with me all these years, both in my own playing, and more importantly, in the ideas I share with my students.

And now, as I am ever more focused on augmenting the repertoire choices of modern pianists, I hear her voice strongly advocating underrepresented composers, advancing gender and racial equality in classical music, and expanding the classical music canon for future generations. What an astounding legacy and how utterly fortunate we are that it continues.