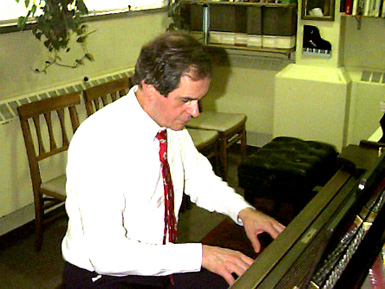

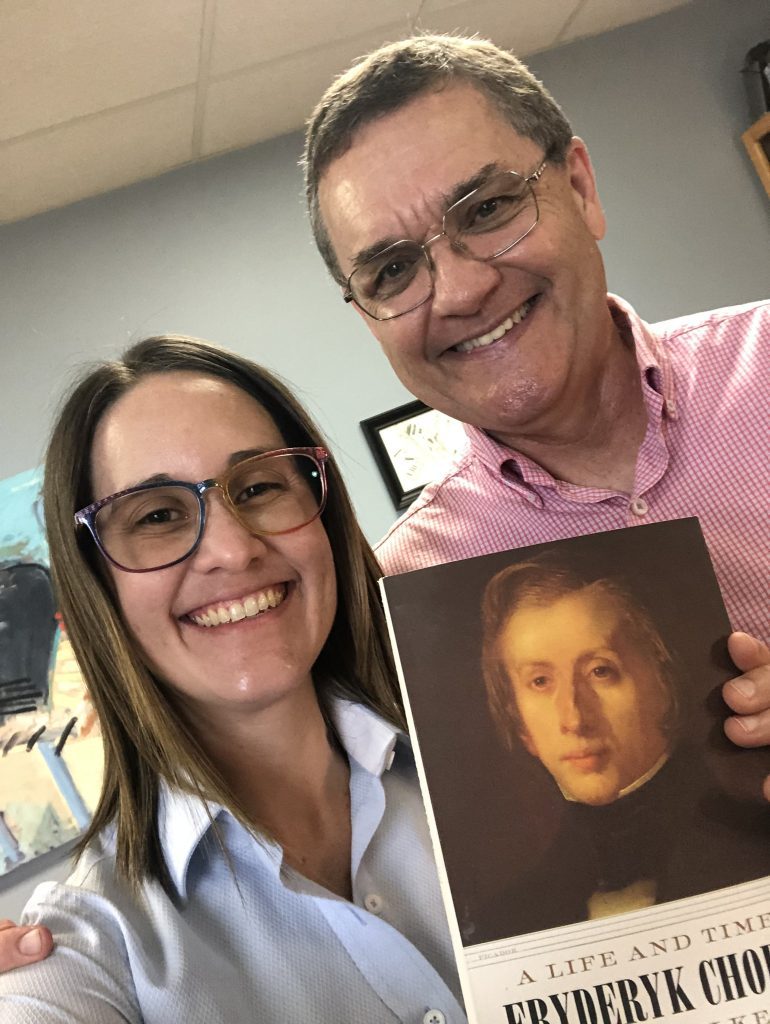

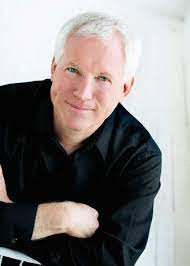

We would like to thank Sara Ernst for this tribute to her mentor, Marvin Blickenstaff. Since 1999, Marvin Blickenstaff has been a beloved faculty member of the New School for Music Study in Kingston, NJ. In honor of the 25th year of his work for NSMS, we recognize the tremendous impact he has had on so many in our profession. Are you interested in teaching at the New School for Music Study? Learn more and apply to our Postgraduate Teaching Program by clicking here.

Marvin Blickenstaff is amazing in so many ways, as pianist, pedagogue, mentor, colleague and friend. I have had the pleasure of knowing him in all of these capacities, and my life has truly been transformed because of this. Among the many attributes Marvin possesses, I wish to celebrate in this tribute is his role as cheerleader extraordinaire. Whether for his students, colleagues, or friends, Marvin will be the first to congratulate the successes of those around him. I have heard his boisterous cheering and applause from the audience, I have heard his heartfelt speeches congratulating others in our profession, and I have received his personal emails commending my professional accomplishments. His genuine love and support of those around him is unparalleled and contributes immensely to our community. Being a musician, pianist, and educator can be difficult (while being tremendously rewarding), and we all need those in our professional lives who reflect to us our own impact and worth. He has provided a tremendous model to me of what that means and how important this is—this is one of the most significant ways we ensure the future of our profession. I encourage us all to follow his example, to project this enthusiasm for piano and teaching into the world, to support our students and colleagues, and to delight in the successes of all those around us.

The Marvin Blickenstaff Institute for Teaching Excellence

In 2023, the Frances Clark Center established the Marvin Blickenstaff Institute for Teaching Excellence in honor of his legacy as a pedagogue. This division of The Frances Clark Center encompasses inclusive teaching programs, teacher education, courses, performance, advocacy, publications, research, and resources that support excellence in piano teaching and learning. To learn more about the Institute, please visit this page.

We extend a heartfelt invitation to join us in commemorating Marvin Blickenstaff’s remarkable contributions by making a donation in his honor. Your generous contribution will help us continue his inspiring work and uphold the standards of excellence in piano teaching and learning for generations to come. To make a meaningful contribution, please visit our donation page today. Thank you for being a part of this legacy.

MORE ON THE POWER OF A PIANO TEACHER

- DISCOVERY PAGE: The Power of a Piano Teacher by Heather Smith

- DISCOVERY PAGE: The Joy of Giving by Heather Smith

- DISCOVERY PAGE: Thank you, Jane! by Sara Ernst

- DISCOVERY PAGE: She Really Took a Chance on Me by Asia Passmore

- DISCOVERY PAGE: A Tribute to John Salmon by Heather Hancock

- DISCOVERY PAGE: A Symphony of Gratitude by Ricardo Pozenatto

- DISCOVERY PAGE: Honoring Amy Merkley and Irene Peery-Fox by Hyrum Arnesen

- DISCOVERY PAGE: Reflections on My Piano Teacher | Honoring Fern Davidson by Marvin Blickenstaff

- DISCOVERY PAGE: Every Student Has a Voice the World Needs to Hear | Honoring Carole Ann Kriewaldt by Leah Claiborne