In her Summer 2021 article “Teaching Adults in Group-Piano Settings: Facilitating the Musical Process,” Pamela Pike gave practical advice about how to teach adults in group settings. Here are five tips for working with adults in groups from her article. Read the full article at https://pianoinspires.com/article/summer-2021-teaching-adults-in-group-piano-settings-facilitating-the-musical-process/.

1. Before creating and designing group-piano classes, teachers should identify which adults they hope to enroll and engage in each group that will be offered.

Considered broadly, adult piano students may be amateur musicians or future professionals. If they are amateurs,1 they may fall anywhere along a continuum from serious piano student to recreational music maker (RMM). Recognizing each adult’s dedication to piano study can help to ascertain how much time they wish to devote to the piano.

2. Adults come to the classroom with preconceived expectations for what they wish to gain from the experience and ideas about how they learn best.

Thus, teachers/facilitators and adult students become partners in the learning experience. In order to facilitate optimal learning among all adults in the group-piano class and a positive group culture, teachers need to consider how they will manage both in- and out-of-class expectations and activities. Thus, from the outset, teachers of adults must plan how they will encourage the appropriate social and musical interaction necessary for success of the group.

3. Many adults, especially those with some formal music training, have preconceived notions about how the piano lesson should be—and may not understand how music making and learning occurs in a group-piano setting.

Remember, also, that the group may not be ideal for every learner.2 Be prepared to direct an adult who will not be well-served by the group experience toward private lessons or another musical alternative.

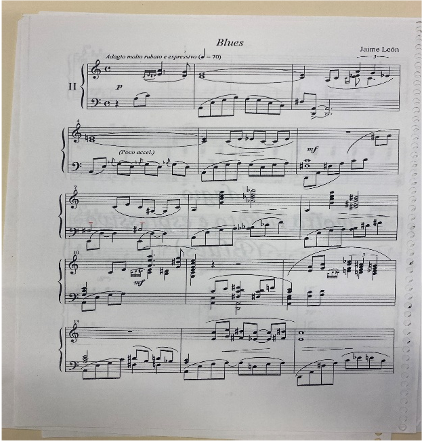

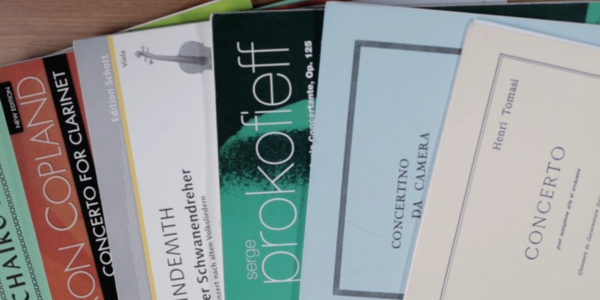

4. Although the possibilities for curriculum design are endless, choose materials, books, and music appropriate for each type of adult group.

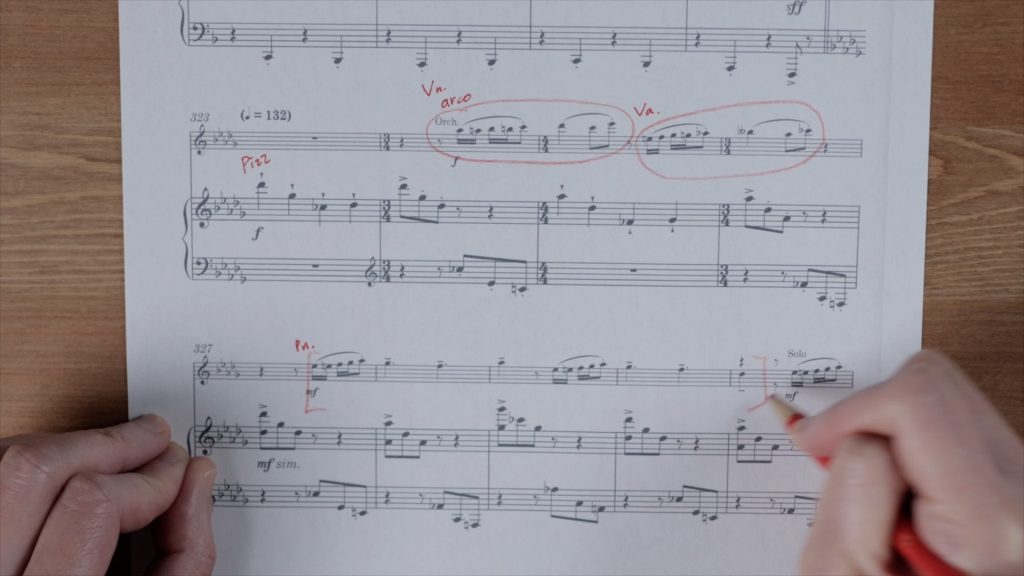

Once group-piano teachers have designed the curriculum for the semester and conveyed the expectations for participation to group members, they must ensure that the group culture is developed and productive group growth is fostered during each class. Facilitators who provide time and space for group members to listen, assess, and speak about their musical experience will, ultimately, support the adults’ learning independence and autonomy, even as the students learn from one another. Most adult students hope to gain a certain amount of independence at the piano, which is especially useful outside of the group setting.

5. Effective teachers consider the sequencing, pacing, and learning objectives for each activity when creating lesson plans.

Ideally, each activity leads seamlessly into the next, with activities providing students opportunities to elaborate upon and increase skill development as the class progresses.3 When teaching groups of adults, the instructor should remain cognizant of the students’ readiness, orientation to learning, and preferred learning styles, but physical and mental changes due to age or lifespan constraints ought to be considered, also.4

For just $36 for the digital version or $48 for the printed issue, you’ll gain access to Piano Magazine, our video series, exclusive discounts, subscriber-exclusive community events, and more! Subscribe here: https://pianoinspires.com/subscribe/.

MORE ON ADULT LEARNERS AND GROUP TEACHING

- MICROCOURSE: Teaching Adults in Groups (from a Pianist’s Guide to Teaching in Groups)

- MAGAZINE ARTICLE: How Do You Develop a Sense of Rhythm in Your Adult Students? by Michelle Conda

- WEBINAR: Designing Effective Learning Environments for Adult Students with Pamela Pike

- MAGAZINE ARTICLE: Incorporating Metacognition into the Group Piano Curriculum by Joann Marie Kirchner

- COURSE: A Pianist’s Guide to Teaching in Groups

Not yet a subscriber? Join for only $7.99/mo or $36/yr.

NOTES

1 The root of the word amateur traces back to French and Latin words that translate to “lover” in English. Used in this sense an amateur pianist is one who pursues study of the instrument for the pure love or joy of it. Some contemporary definitions of amateur reference incompetence. However, throughout this article the term amateur will be used to reference a musician who, although not a professional, loves studying or playing the piano.

2 Frances Clark wrote that group teaching is successful when (among other things) “the teacher believes that the group learning situation is best for every student in the group.” See Frances Clark, Questions and Answers (Kingston: Frances Clark Center, 1992): 183.

3 For a more detailed discussion of individual learning styles, preferred learning modes, and cognitive strategies that improve learning and reinforce individual learning preferences in group-piano settings see chapter 4 in Pamela D. Pike, Dynamic Group-Piano Teaching, Routledge, 2017.

4 See Andrea Creech, Susan Hallam, Maria Varvarigou, & Hillary McQueen, Active Ageing with Music, Institute of Education Press, 2014; Cyril O. Houle, Patterns of Learning, Jossey-Bass, 1984; Pike, Group-Piano, chapter 7.

Pamela D. Pike is the Spillman Professor of Piano Pedagogy and Associate Dean of Research at Louisiana State University. As an active researcher of pedagogical topics, she is a sought-after speaker and clinician. Pike has published articles, book chapters and full-length books, and is editor-in-chief of the Piano Magazine.