Check out Sarah Rushing’s archived webinar of Margaret Bonds: Troubled Water, where she explores the preparation, practice, and interpretation of this unique piece.

1. Margaret Bonds was raised by four independent, career-oriented women.

At the tender age of four, Bonds’s parents divorced. Instead of growing up in a traditional family structure, Bonds was raised by her mother, two aunts, and maternal grandmother. These strong women supported Bonds in her passion for composing, helping her to see a life beyond the stereotypical roles women were otherwise expected to adopt in the 1920s and 30s. After her divorce, Margaret’s mother chose to readopt her maiden name, Bonds, perhaps later inspiring Margaret to keep her own surname when she married. Bonds continued to defy cultural norms throughout her life, including when she chose to move to Los Angeles alone, without her husband or 21-year-old daughter, in order to pursue new directions in her career.1

2. When Margaret was young, the Bonds family took in several Black artists, including Florence Price.

Margaret’s mother, Estella Bonds, opened the family home to the large community of Black artists in Chicago. As a result, the young Margaret frequently interacted with the likes of Will Marion Cook, Lillian Evanti, Abbie Mitchell, and Langston Hughes. Florence Price became a more permanent visitor, living with the Bonds family for a time. The community Estella created supported Price personally and professionally, often helping with tasks such as copying, extracting, and correcting scores. Soon after, Margaret studied composition with Price.2

The community Estella created supported Price personally and professionally…

3. Bonds was admitted to Northwestern University at the young age of 16.

While at Northwestern, Bonds experienced profound racism. Though she was allowed to study and attend classes, she wasn’t permitted to live on campus or use the facilities. Instead, she frequented the Evanston Public Library, where she first encountered the poetry of Langston Hughes. Hughes would become an important source of friendship and artistic inspiration later in her life, as she later set many of his poems to music.3, 4

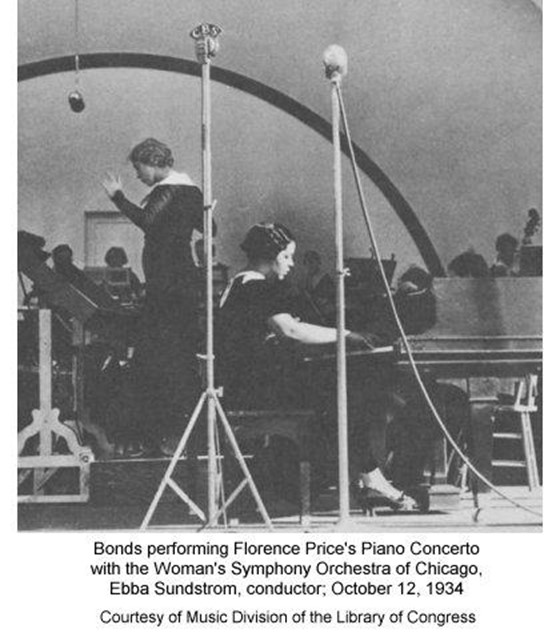

4. Bonds was the first Black soloist to appear with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Bonds performed Price’s Piano Concerto at the 1933 World’s Fair held in Chicago. This performance was preceded by another notable achievement for the young composer: winning the Wanamaker Prize in 1932 for her vocal composition, Sea Ghost. These accomplishments helped launch the young musician’s career.5

5. Bonds considered herself a musician and humanitarian, working tirelessly to dispel racial discrimination.

In addition to her activity as a composer, Bonds was passionate about performing and promoting the music of other Black musicians. In 1947, she hired a manager who helped her organize a series of concerts and lectures at Historically Black Colleges and Universities throughout the south. In the 1960s, she embarked on a similar project in New York City.5

Other resources you might enjoy

- DISCOVERY POST: This Week in Piano History: National Black Women in Jazz and the Arts Day by Curtis Pavey

- DISCOVERY POST: Five Things You Might Not Know About Florence Price by Lia Jenson-Abbott

- PIANO MAGAZINE ARTICLE: Sounding Florence Price for a New Century by Samantha Ege

- PIANO MAGAZINE ARTICLE: Celebrating the 100th Anniversary of Women’s Suffrage by Tony Caramia

- WEBINAR ARCHIVE: Margaret Bonds: Troubled Water by Sarah Rushing

- VIDEO: Margaret Bonds: Troubled Water by Sarah Rushing

- Use our search feature to discover more!

Not yet a subscriber? Join for only $7.99/mo or $36/yr.

Sources

- Peebles, Sarah Louise. “The Use of the Spiritual in the Piano Works of Two African American Women Composers – Florence B. Price and Margaret Bonds.” The University of Mississippi, 2008.

- Walker-Hill, Helen. From Spirituals to Symphonies: African-American Women Composers and Their Music. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002.

- Green, Mildred Denby. Black Women Composers: A Genesis. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1983.

- Walker-Hill, Helen. From Spirituals to Symphonies: African-American Women Composers and Their Music. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002.

- Jackson, Barbara Garvey, and Dominique-René de Lerma. “Bonds [Richardson], Margaret Allison.” Grove Music Online. 30 Sep. 2020; Accessed 6 Jan. 2023. www-oxfordmusiconline-com.databases.wtamu.edu/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-90000318953.

- Walker-Hill, Helen. From Spirituals to Symphonies: African-American Women Composers and Their Music. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002.