Double Your Impact on the Future of Piano Education

PRESS RELEASE: 30 JANUARY 2025

For Immediate Release

Contact: Heather Smith, Director of Development and Advancement

hsmith@francesclarkcenter.org

Kingston, NJ – January 30, 2025

The Frances Clark Center for Keyboard Pedagogy proudly announces a historic opportunity to advance the future of piano education. An anonymous donor has pledged a $100,000 matching gift to benefit the Piano Inspires Legacy Circle and The Frances Clark Center Endowment. This remarkable commitment will match every dollar contributed during the campaign, doubling the impact of each donation and advancing the Center’s mission to inspire and support piano teachers and students worldwide.

“We are deeply honored to receive this transformative gift from one of our generous donors,” said Dr. Jennifer Snow, President and CEO. “The opportunity to launch a matching gift campaign around the newly created Piano Inspires Legacy Circle motivates all of us to focus on the value and importance of a sustainable future. The impact of this powerful gift is far reaching and will allow us to more fully realize our mission in support of our dedicated piano education community.”

Amplifying Support for a Growing Mission

This matching campaign arrives at a pivotal time as The Frances Clark Center continues to expand its reach and influence. Contributions will directly support initiatives that inspire and empower educators and students, strengthening the Center’s financial foundation and expanding its ability to create meaningful, lasting change in piano education.

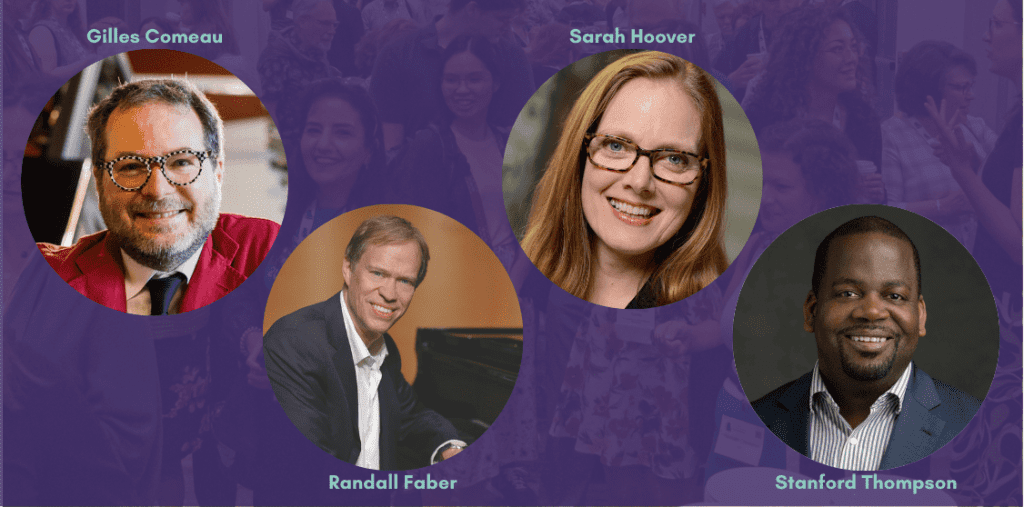

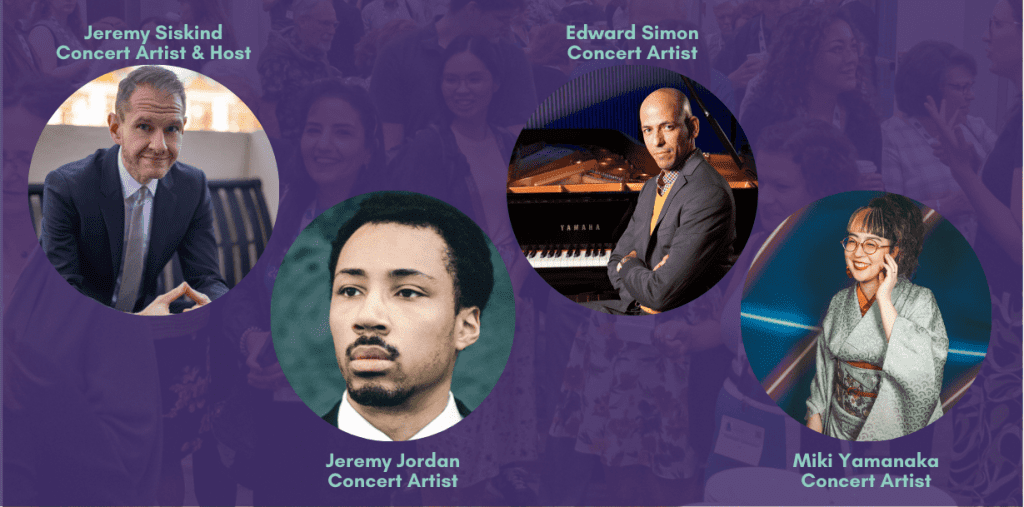

Donor support will uphold the Center’s core values of accessibility, innovation, and excellence while advancing a wide range of initiatives, including The Piano Conference: NCKP, The New School for Music Study, Marvin Blickenstaff Institute for Teaching Excellence, Teacher Education programs, Piano Education Press, and publications such as Piano Magazine, Piano Inspires Kids, and Journal of Piano Research. These resources continue to inspire and equip piano educators and students worldwide, making piano education accessible and impactful for future generations.

Your Gift Doubled: A Meaningful Opportunity

Every dollar contributed during this campaign will be matched, up to $100,000, effectively doubling the impact of each gift. Donors may choose to make a one-time donation, pledge multi-year support, or join the Piano Inspires Legacy Circle. Each contribution directly supports the Center’s ability to sustain and grow its programs, benefiting students, teachers, and communities around the world.

“Endowments are markers of mature, responsible, and sustainable organizations because they provide a stream of revenue in perpetuity,” said Dr. Samuel S. Holland, Chairman of the Board of Trustees. “Donors can take pride in knowing their gifts will have a profound and lasting impact on the future of piano education. As we continue to innovate and expand, the support of our community is more critical than ever. Together, we can secure the future of piano education and honor Frances Clark’s enduring legacy.”

Act Now: Your Legacy Starts Here

The matching campaign runs through August 31, 2025. Take advantage of this opportunity to double your impact and contribute to the future of piano education. To make your gift or learn more, visit Piano Inspires Legacy Circle or contact Heather Smith, Director of Development and Advancement, at hsmith@francesclarkcenter.org.

!["His [Chanon's] music does not always reference his Navajo heritage directly, but rather embodies the spirit of innovation and exploration that drives his work as a composer." - C. Chee](https://pianoinspires.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/image-2.png)