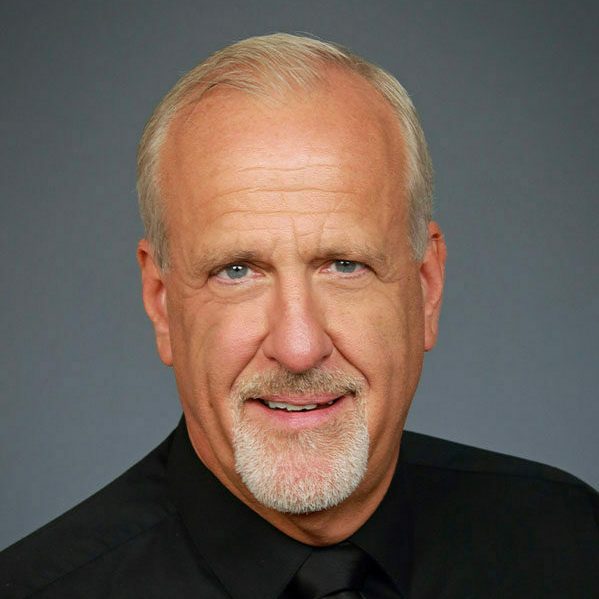

To celebrate the latest episode of the Piano Inspires Podcast featuring Courtney Crappell, we are sharing an excerpted transcript of his conversation with Jennifer Snow. Want to learn more about Crappell? Check out the latest installment of the Piano Inspires Podcast. To learn more, visit pianoinspires.com. Listen to our latest episode with Crappell on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or our website!

Jennifer Snow: What is your thought—as somebody who’s running an institution of higher learning—about the role of musicians in the world today? With the level of disruption and change we see, what are we preparing people for?

Courtney Crappell: I love that question. When I look at what we’ve been doing in academia or even as piano teachers, I think that our view has been much too narrow. I think a lot of people are figuring this out now, because the impact we can have is so much larger than where we’ve thought it would be, and that’s really exciting.

So let me be more specific, I guess, about that. If your kid is going to go to university and say, “Oh, I’m going to major in music.” And you’re like, “Okay, well, that’s going to be hard. How are you going to have a career?” And thoughts, you know, really, people have a binary impression of what you do with that.

JS: Right.

CC: You’re going to perform, and if that doesn’t work out, or maybe, you know, if it is your passion, you’re going to teach. And it’s this this-or-that mentality. Of course, we, who’ve been in it, know there’s a lot of other pathways there, but we haven’t done a good job of letting the rest of the world know that. Really, we have such an opportunity to let more people know of the impact of the arts. So I feel like we really, I mean the teaching-performing, binary approach, we’ve been looking through the peephole in the door, and it’s time to open the whole door.

When I talk to groups of parents with their students who are auditioning, I say the arts are all around you. They’re in the phones, the sounds your phones make. They’re in the clothes you’re wearing. They’re on the billboards you see on the side of the road. They’re everywhere. Employers are looking for creatives to hire, and I do believe that this understanding that the arts are part of the lives, rather than this optional add-on at the end of the day, “All right, we’re focused on your STEM preparation for a career. Now, let’s go tack on some piano lessons, because you gotta.”

Two, the piano lessons are the fuel for creativity in the STEM fields. You know, as recently in Boston I was talking to an MIT faculty member [who is] retired now, but she was part of—the center doesn’t exist anymore—the Center for Advanced Visual Studies. And it was a group of people who believed that the marriage of technology and the arts was going to unlock significant secrets, you know, was going to lead to discoveries that couldn’t happen, or even just fuel the discoveries in specific disciplines. It’s fascinating to see work like that, because you think, MIT, well, we don’t really question the value of MIT, right? Like there’s IP coming out. We take it for granted these days, but look at music, theater and the arts at MIT. It’s the fuel for that.

So where are we going? I mean, institutions like mine. I’m at a public state university, and I think there’s some degree plans that we’ve really not been focused on as academic faculty in the arts, specifically the liberal arts, Bachelor of Arts degrees, which are intended to prepare people for a broad variety of pathways. And you know, maybe this prediction won’t come true, but I think that the Bachelor of Arts degree is going to become a large focus for us, and more so than the Bachelor of Music degrees, which are performance-based. There’s not enough room in the degree plans. We continue to try to make them more modern and relevant to help these students be successful. So, you know, we’ve done things like, “All right, do your Bachelor of Music, but you should also do an arts entrepreneurship program, because you’re going to need that.”

Well, what if you did a Bachelor of Arts degree, and you just build this into a broader portfolio? Whether it’s, you know, college prep programs at high schools for the arts or undergraduate degrees that are launch pads into other careers, we know these pathways exist because people have those jobs. You know, I talked to scientists who trained as musicians, lawyers who were actors. The list goes on and on and on. We know that happens, and we’ll talk about that when we’re promoting the value of the arts, study in the arts; but we, I don’t think we’ve put our money where our mouth is to say, let’s really invest in that. Let’s commit to those programs. So I feel like we’re on the cusp. Like I said, we just need to open the door, and there’s concerns about shrinking budgets or low recruiting numbers, those problems won’t exist if people understand the value. So that’s where I think we’re heading.

JS: That’s exciting.

If you enjoyed this excerpt from Piano Inspires Podcast’s latest episode, listen to the entire episode with Courtney Crappell on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or our website!

MORE ON COURTNEY CRAPPELL

- PIANO MAGAZINE ARTICLE: Time-Saving Tips for Teachers by Steve Betts

- PIANO MAGAZINE ARTICLE: What are your thoughts on the future of piano teaching? by Pete Jutras, Mario Ajero, Linda Christensen, Alejandro Cremaschi, Jennifer Foxx, Andrea McAlister, Jennifer Snow, Wendy Stevens, Kathleen Thiesen, Leila Viss, and Kristin Yost

- PIANO MAGAZINE ARTICLE: Twenty-First Century Pedagogy: A Whole New World Again by Andrea McAlister and Courtney Crappell

- WEBINAR: Town Hall Discussion: Piano in Higher Education in the time of COVID-19 with Erin Bennett, David Cartledge, Leah Claiborne, Courtney Crappell, and Margaret Young

- PIANO MAGAZINE ARTICLE: Spring 2020: Book Review: Teaching Piano Pedagogy: A Guidebook for Training Effective Teachers by Ann DuHamel