Pianist and educator Sara Davis Buechner discusses her musical journey, the saving power of music, and advocacy, with Craig Sale in this episode of the Piano Inspires Podcast.

Podcast: Play in new window

Pianist and educator Sara Davis Buechner discusses her musical journey, the saving power of music, and advocacy, with Craig Sale in this episode of the Piano Inspires Podcast.

Podcast: Play in new window

To celebrate the latest episode of Piano Inspires Podcast featuring Sara Davis Buechner, we are sharing an excerpted transcript of her conversation with Craig Sale. Want to learn more about Buechner? Check out the latest installment of the Piano Inspires Podcast. To learn more, visit pianoinspires.com. Listen to our latest episode with Buechner on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or our website!

Sara Davis Buechner: Katie Welch’s first piano lesson: she came in with a big frown on her face. I said, “Are you in a bad mood?” She says, “Yeah!” I said, “Why are you in a bad mood?” “I hate the piano!” I said, “So do I! You know, I hate the piano a lot. Let’s beat it up.” I said, “Sit here with me.” And we just bam, bam, bam [demonstrates hitting surface]. We hit the keys of the piano until she got tired. I just let her do that until she [panting out of breath]. And then I said, “Okay, now are you tired of hitting the piano?” And she said, “Yeah.” I said, “Let me show you how the piano can maybe be your friend.” I played a beautiful Chopin nocturne with little stars. “Oh, that’s really nice.”

Anyway, three years later, she came in for her last lesson. She didn’t know it was her last lesson when it was done. I said, “Katie, I have to tell you something. I’m, I’m—I won’t be your piano teacher next year. I’m moving to the city of Vancouver. I’m joining a college faculty there.” And she said, “Where’s Vancouver?” And I drew a little map for her and I showed her. She burst out crying. I said, “Why are you crying? What’s the upset?” You know? She said, “I love the piano.”

Craig Sale: Oh!

SDB: It’s the best teaching job I ever did. You know? Because, you know, it’s interesting. I mean, I love my college students, of course. However, they’re at an age where they have specific goals in mind, they have to pass the jury, they’re entering a competition, they’re auditioning for a job. They need this skill or that skill, you know. It’s very goal oriented. With young children, I’m very aware that I don’t know what their goals are, they don’t know what their goals are. They’re unformed and the main thing is that you want to prepare them that if they do decide to be a teacher of music, to be a choir director, to be an accompanist, to be a teacher of solfège, you know, to be a jazz band leader, whatever, that they have a very, very positive feeling about it.

If you enjoyed this excerpt from Piano Inspires Podcast’s latest episode, listen to the entire episode with Sara Davis Buechner on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or our website!

Not yet a subscriber? Join for only $7.99/mo or $36/yr.

We hope you enjoy learning about one of the publication projects of the Frances Clark Center—publishing piano works of Thomas H. Kerr Jr. Please join us for our Publications Launch Party with Susanna Garcia and William Chapman Nyaho celebrating the first of these publications, Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel?: Concert Scherzo for Two Pianos, Four Hands. The event will occur on Wednesday, May 8th at 11:00am ET. Learn more and register here.

Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel?: Concert Scherzo for Two Pianos, Four Hands is a set of six variations and a coda based on the Negro spiritual. Composed in 1940 by pianist and composer Thomas Henderson Kerr Jr. for his performances on the Black College Circuit during the 1940s, it is an effective showpiece for advanced pianists.

Kerr described it this way: “The piece sets forth the theme transparently and saucily then plunges into querulous, propulsive and percussive ostinato (Allegro Barbaro), with a surprise ending. After a breathing pause (for both players and listeners) comes a slow expressive section (Andante Sognando)…There are two brittle, playful variations (Scherzando) and a ‘Tempo Grandioso’ which leads to a coda which sweeps the players off the stage.”

Nyaho/Garcia Piano Duo

Five by Four

MSR Classics: MS1753

Click here to listen on Spotify

Thomas Henderson Kerr Jr. (1915–88) was born in Baltimore, Maryland. He began playing and studying piano at an early age. He taught himself the organ and, as early as fourteen, played for church services, as well as in Baltimore’s nightclubs. As a young man, Kerr wanted to attend Peabody Institute, but, at that time, African Americans were not admitted. He instead attended Howard University for one year, then transferred to the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York, where he earned three degrees: a bachelor of music in piano, a bachelor of music in theory, and a master of music in theory. At Eastman he studied piano with Cécile Genhart (1898–1983). He graduated summa cum laude. In 1943, Kerr returned to Howard University as Professor of Piano and served as chair of the piano department until his retirement in 1976.

Kerr’s catalogue lists over 150 compositions for piano, organ, voice, chorus, and chamber ensembles, most of which have never been published. They are preserved in manuscripts at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Archives and Rare Books Division, in New York City.

This is the first published edition of this composition and the first in a series of three piano works by Thomas H. Kerr Jr. to be published by the Frances Clark Center.

To learn more and purchase Thomas H. Kerr Jr.’s Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel?: Concert Scherzo for Two Pianos, Four Hands, click here.

MORE ON WILLIAM CHAPMAN NYAHO

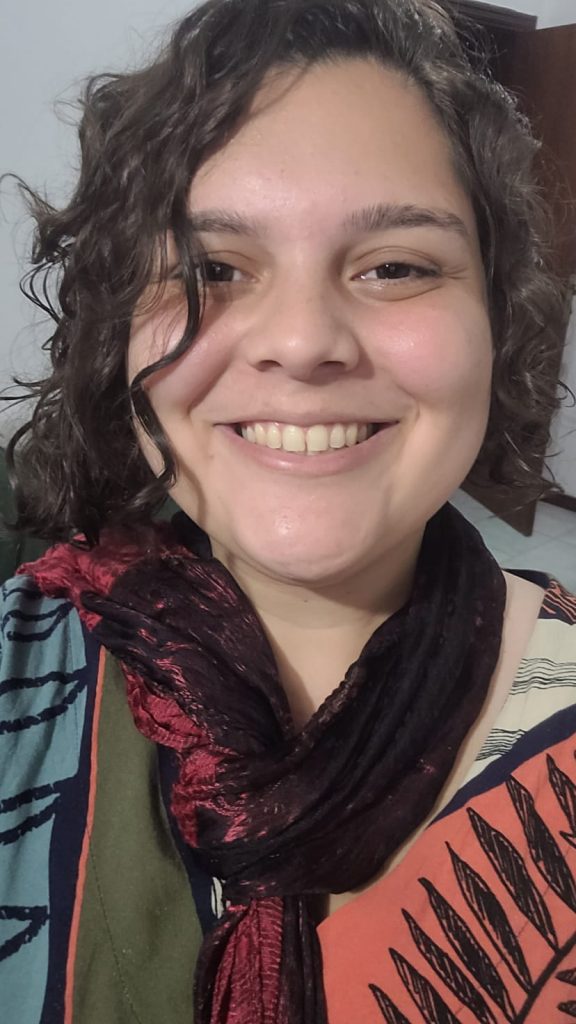

We would like to thank Paulina Zamora for this insightful article on her experiences growing up as a musician in Chile. Want to learn more about international teaching practices and repertoire? Register for our 2024 Summer Intensive Seminar “An International Exploration of Piano Teaching Literature” lead by Leah Claiborne and Luis Sanchez. Early bird registration pricing has been extended until May 15, 2024! Learn more and register here.

The international column has frequently focused on comparing music education systems in different parts of the world, with previous articles discussing subjects such as the Australian Music Examinations Board, as well as thoughts from professors of Asian conservatories about sending students abroad to Europe. In continuing this trend, I sought out my former classmate Paulina Zamora, whose journey as student and professor in North and South America presents a unique perspective on the music training in both regions that has proven to be wonderfully illuminating. -Jerry Wong, International Column Editor

My trajectory as a concert pianist, teacher, and scholar followed a similar international pathway as many musicians whose native origins are far from the traditionally accepted educational music centers of the world. I excelled in my native Chilean environment until completion of my undergraduate degree and went on to graduate studies abroad. After twenty years of artistic and professional career growth, I returned to Chile and began to forge a teaching career in academia, while steadily building international opportunities for performances and masterclasses.

My beginnings were similar to that of a child prodigy, but I prefer to think that I was a very talented girl with lots of potential and a serious, no-nonsense attitude. From the age of five I intuitively knew I would dedicate my life to music. As the youngest of three sisters, my father’s immediate attention went to fostering a musical upbringing in my oldest sister. I can recall interrupting my sister’s piano lessons and begging my father to teach me as well. After many bold attempts for attention, my father conceded. It is so meaningful to me that as adults, my oldest sister became a beautiful ballet dancer and I am now a professional pianist. We often rejoice in the commonalities between these two art forms.

The Music Department at the University of Chile offers an eight-year pre-collegiate program which is referred to as the Basic Period (conservatory level) and a five-year Undergraduate degree. I undertook studies at both levels, receiving the standard two piano lessons per week during both courses of study. During the Basic Period, piano lessons were complemented with fundamental courses such as Theory, Harmony, and Introduction to Music History. While pursuing my undergraduate, I received the traditional curriculum of a bachelor’s degree in the United States. Furthermore, during my early conservatory years, I would spend summers receiving daily piano lessons. An outcome of this intense training was to play my first formal recital at age nine, performing from memory the fifteen two-voice Inventions by Bach. This was followed, a year later, by the Fifteen Sinfonias. At that time, I did not feel comfortable questioning my teachers or proposing different options and, of course, this exercise gave me invaluable lessons in self-discipline and focus. Years later I would return to these works in recording and editing projects. Having said all of that, I do refrain from reassigning this task to young students of my own!

Pursuing graduate studies in the Unites States presented all sorts of enlightenment and change. The most obvious difference was the adjustment from two or more hours per week of lessons to just to one hour per week, and sometimes less if the artist-teacher was away. The reasoning behind this amount of instruction made sense to me, but it took me a few months to adjust. Ultimately, acquiring self-reliance and independent musical thinking was a valuable lesson from those years.

During my studies at the Eastman School of Music and Indiana University, I had moments to reflect on the wonderful teaching I had received in Chile, while also embracing the opportunity to understand more fully what still needed to be learned. I was mesmerized by the infrastructure of the schools: the buildings themselves, the magnificent libraries, the many practice rooms with decent pianos, stunning concert halls, and the rich musical life of each respective city. The academic level of both schools was outstanding, and I felt this from my first days of attending music-related classes.

We hope you enjoyed reading this excerpt from Paulina Zamora’s article, “A Continuum Between Teaching Styles: Reflections from the US and Chile.” Read the full article by clicking here.

MORE ON LATIN AMERICAN MUSICIANS AND COMPOSERS

Join Angelin Chang, the first female American classical pianist and first pianist of Asian descent to win a Grammy and first Artist-in-Residence at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. as she discusses the importance of advocating for music for all. Special thanks to our host for this episode, Andrea McAlister.

Podcast: Play in new window

To celebrate the latest episode of Piano Inspires Podcast featuring Angelin Chang we are sharing an excerpted transcript of his conversation with Andrea McAlister. Want to learn more about Chang? Check out the latest installment of the Piano Inspires Podcast. To learn more, visit pianoinspires.com. Listen to our latest episode with Chang on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or our website!

Andrea McAlister: I know we’ve talked a lot about music in the world and how we can make a change. I want to look forward now. We’re at this time where there is a lot of division and there is a lot of disagreement, and there’s a lot of tension in many places. Fortunately, we’re experiencing the opposite of that this week in this environment that we’re currently in, as we are all surrounded by pianists and teachers. We’re feeling it. How do we carry this out into the world? What does it look like? Let’s say, you know, if we fast forward ten years and say, “How has music transformed the world? How can we take this message out and really make a difference?” I know, we might think that—well just in my small little community, I can do a little bit. How does that change the world?

Angelin Chang: Planting the seeds does change the world. For me, I think the message is also understanding that the arts—music—is for everyone. I mean, a lot of times we’re talking about classical music—highbrow music—but, where did it originate? It wasn’t highbrow, we made it highbrow, so to speak. Nothing wrong with highbrow or lowbrow, or medium brow. You know? It’s for everyone. That’s one of the things I learned at the GRAMMYs too, because when I was nominated, I felt like, “I’m going to be a fish out of water here being a classical musician,” because all I knew was what I saw on primetime TV. But even then, going there, it was a community. Mutual respect all around for all genres. It wasn’t, “Oh, because you’re not pop you’re not hip.” It wasn’t that at all. It’s just that, you know, primetime TV, there’s just a small segment of what they could, you know, make money off of. Anyway, right, nothing wrong with that. Because those type of things would help fund things that were, you know, may need some more support? Did you know that the GRAMMYs is actually the largest fundraiser for all their activities, including a lot of great programs that help musicians in need, for example?

AM: That’s fabulous.

AC: Yeah, and we don’t see that, and not until I won, did I even know about some of these programs that were behind the scenes, like—oh, my gosh, there’s so much more. Just like there’s so much more here in our conference. Each individual brings so much, but, you know, the organizational part—to institute what we value in that sense that helps the next generation. Now with all the division and all that, I think partly it’s because there’s not this type of communication and understanding. So there’s the tendency for us to just be in our group that we feel safe and secure, and everything else out there is like, “No, no, don’t touch that.” Whereas I feel it’s the opposite that needs to happen. For example, when I went to Nepal and it’s like, “Okay, I’m very comfortable again now in this wonderful palace of a hotel and everything like this.” Yeah, it’s going beyond and actually noticing those things. And to be, “Hey, these are these are humans these are we can interact. We have something to benefit each other that can help make things better.” Or an understanding—it’s not that you have to agree with the other stuff, but at least understand or at least communicate. You can agree to disagree and still understand and have that common goal of making something for the better. Now, we can decide like, “Okay, we’ll try your way this time, try our way that time and see. Okay, then be objective.” I know it’s very difficult because a lot of times people don’t want to see that. I think part of it is taking off those blinders and just being open.

Even if you disagree with something like—how many times have you gone to a concert and it’s like, “Oh, I wouldn’t do it that way, I wouldn’t do that.” But you can’t deny that whatever they gave was like, “Wow, they worked on that. They made it special. They made it their own.” That’s what makes the world turn—embracing our uniqueness in that sense. And it’s great that we’re all different, but we’re all the same at the same time. Understanding that at the core, there’s certain things that we all want and that we all need. That feeling of security. There are a lot of people here where we’re changing the status quo feel very insecure. It’s not that necessarily I think that they’re feeling that, you know, they’re in the right, we’re in the wrong or just, they’re just wanting to hold power. Folks might lash out because they feel insecure, not because they feel powerful. I think it’s very important to understand some of the signs that we might interpret, aren’t necessarily what’s really going on. See what we can all do, to have that mutual understanding for world peace and human harmony.

AM: Just a small little thing we as musicians can, yeah—. I say it kind of facetiously but seriously, that music can do that as you are proving that day in and day out. We really thank you for all the work you have done and are doing to create that place that we all hope we can get to someday, but we’re also in it now. We’re also seeing how it’s happening.

AC: It’s happening.

AM: Music is that connector and it’s just beautiful.

If you enjoyed this excerpt from Piano Inspires Podcast’s latest episode, listen to the entire episode with Angelin Chang on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or our website!

MORE ON ANGELIN CHANG

We would like to thank Marianne Williams for this tribute to her teacher, Marvin Blickenstaff. As we continue the season of gratitude and giving, we pay tribute to piano teachers from around the country who are transforming the lives of their students. Students, parents, and colleagues are honoring piano teachers from their communities as part of the “Power of a Piano Teacher” campaign. We welcome you to celebrate your own teacher by sharing a tribute with us and donating to The Frances Clark Center.

I met Marvin Blickenstaff when I was a high school senior attending the Summer Piano Clinic at UNC-Chapel Hill in 1969. At the time, he served as the Director and also held master classes during the clinic. I played Griffes’ Notturno, Op.6, No. 2 for him in one of those classes. I had never felt the tenderness in this piece until he explained and demonstrated it for me. After the class, I wrote to him requesting that I be allowed to study with him at UNC.

I studied with him from 1970-1974 and I also took his piano pedagogy class. His enthusiasm for all the things that a piano teacher needed to learn and share in order to instill the love of the piano in others was contagious. My piano abilities were forever influenced by my studies with him. Shaping of phrases, improving the tone of a note, technical exercises, and learning to listen to myself were all new and wonderful things to me. He knew my limitations (small hands!) and quickly helped me learn to find repertoire that I would be able to enjoy playing and teaching! Mr. Blickenstaff also made me feel more confident in my ability than I had ever felt before. My piano training from him was complete and covered all eras of piano music. I especially loved learning all the Bach Two-Part Inventions in my freshman year, and still love playing them with all the ornaments that Bach indicated.

After graduating in 1974 as a Bachelor of Music Education with a Major in Piano, I moved around a bit with my husband, but in every place we lived, I set up a piano studio. I have taught continuously since then with a few breaks to have two sons, and I also taught classroom music for thirty years as well.

Thanks to what I learned from Mr. Blickenstaff, and what I am continuing to learn through articles, webinars, and the program at NSMS, I have an intense love of learning new pieces and sharing this love with my students. I still use the same method of teaching all major and minor scales that I learned in college and still have the original printouts with exercises and examples that he gave me.

I have lost track of the total number of students that I have taught since 1974, but I like to think that they are part of Mr. Blickenstaff’s legacy. He taught me how to interact with my students and inspired me to strive to instill in them the same love of music at the piano that he gave to me.

In 2023, the Frances Clark Center established the Marvin Blickenstaff Institute for Teaching Excellence in honor of his legacy as a pedagogue. This division of The Frances Clark Center encompasses inclusive teaching programs, teacher education, courses, performance, advocacy, publications, research, and resources that support excellence in piano teaching and learning. To learn more about the Institute, please visit this page.

We extend a heartfelt invitation to join us in commemorating Marvin Blickenstaff’s remarkable contributions by making a donation in his honor. Your generous contribution will help us continue his inspiring work and uphold the standards of excellence in piano teaching and learning for generations to come. To make a meaningful contribution, please visit our donation page today. Thank you for being a part of this legacy.

MORE ON THE POWER OF A PIANO TEACHER

We are delighted to share a few highlights from the work of young professionals throughout the United States and Canada. Each of these videos comes from our Inspiring Artistry video collection. To learn more and submit a proposal for a future Inspiring Artistry or From the Artist Bench video, please click here.

by Charlotte Tang

When approaching this Scarlatti work for the first time, Tang recommends the following as an initial focus:

by Mengyu Song

When presenting Nakada’s The Sad Waltz, Song suggests the following activities:

by Shelby Nord

When working with a student on the expressive elements of this Tansman piece, Nord suggests:

by Ricardo Pozenatto

Students often struggle with physical coordination. To help remedy this challenge, Pozenatto offers the following tips:

by Kate Acone

Before a student learns The Easy Winners by Scott Joplin, it may help to introduce the piece with the following activities that Acone describes:

To learn more and submit a proposal for a future Inspiring Artistry or From the Artist Bench video, please click here.

In this episode of Piano Inspires Podcast, Chee-Hwa Tan talks with Alejandro Cremaschi about her compositional process, the process of storytelling, and learning technique through emotion.

Podcast: Play in new window

To celebrate the latest episode of Piano Inspires Podcast featuring Chee-Hwa Tan, we are sharing an excerpted transcript of her conversation with Alejandro Cremaschi. Want to learn more about Tan? Check out the latest installment of the Piano Inspires Podcast. To learn more, visit pianoinspires.com. Listen to our latest episode with Tan on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or our website!

Alejandro Cremaschi: Where are you seeing our field going now? What’s your impression? Are you thinking about these things: you know, the classical music making, piano playing? Where are we, and where are we going? What do you see in the future?

Chee-Hwa Tan: I think that music will always be relevant. We all need that. I mean, we have this craving for beauty. Now, I think if we all insist on our little boxes, then we look within that box and say, “well, where’s it going?” I can’t answer that. I think as long as we focus—as far as in piano and teaching—if we keep reminding ourselves, asking ourselves, like, during the pandemic, I thought we should be asking, what do they need? What does this student need right now? My grad students—everything has shut down. How about I just throw out my course and do a different—what do they need? Do they need all this content and information? You know what I’m saying?

Or do they need to connect because they’re looking rather depressed across that Zoom screen, you know, in their apartments. So I think that if we think back to what Frances Clark said, you know, that first you teach the student. And I say, I reword that, first you see the person, you see the person, and that person can make music, and that person could feel like an artist. If they feel a little bit like an artist, maybe not to the level of our classical standards, but they feel a bit like an artist, they are going to be hooked on music for the rest of their lives, and they will be supporters of the arts one day, or they may be innovative in their music. So I’ve had to just move out of that box a little bit and I was definitely in that box. I mean, you know, it’s been a continued growth process. I think that music, as long as we keep—we don’t become segregated or elite, you know, and I don’t say lower the standard you know—but value someone’s music making. Find something, you know, that’s at least something that’s special. Try to look at it that way because otherwise we kill our own joy.

AC: Right?

CHT: I was killing my own joy sitting there and noticing everything, you know, when that’s not the way it ever was anyway, you know? Now we are in a world of super edits. Right? Yeah, so I think there’s great hope for music. I think we just need to flex with it. We don’t have to lower our standards, we just need to open our vision, a perspective to the bigger picture. You know, ask us for that gift to be able to see the bigger picture and see people first, because people matter. I tell my graduate students that—as I was leaving DU—that people matter more than the product. People matter more. That’s what you leave behind: the people and the relationships.

If you enjoyed this excerpt from Piano Inspires Podcast’s latest episode, listen to the entire episode with Chee-Hwa Tan on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or our website!

MORE ON CHEE-HWA TAN

Students throughout the United States responded to our call for proposals for the 2024 Collegiate Connections virtual event, which will highlight innovative group projects at universities throughout the United States. The Frances Clark Center is pleased to announce the selected proposals for our event on Friday, April 26, 2024 from 11:00 AM to 12:30 PM Eastern. Interested in attending this virtual event? Learn more and register by clicking here.

This presentation highlights the contribution of women who ventured into music composition when they were not encouraged to do so and were instead expected to take on the role of performer or teacher. To address this issue, we have selected three composers who were born in the second half of the 19th century in different countries: Chiquinha Gonzaga (1847-1935) – Brazil, Cecile Chaminade (1857-1944) – France, and Florence Price (1887-1953) – USA. These women bravely participated in various musical scenarios and composed a large amount of music, especially for piano.The selected composers have vastly different styles, but they all have a significant number of works in their catalog that are suitable for intermediate-level learners and have excellent pedagogical value.

Elementary piano methods today utilize a majority of consonant sounding pieces in various styles. Rather than gatekeeping modern, atonal sounds to the advanced realm of music, it is both possible and intuitive to introduce the sounds of atonality to children’s methods. By presenting the concepts of bi-tonality, clusters, polyrhythms, improvisation, and more, young students will experience the sounds of modern music naturally. The aim of this project is to provide a model with examples of how these modern concepts can be reduced within palatable lessons to fit within an elementary method. As a group project, three pieces selected from various children’s methods have been creatively adapted to introduce contemporary compositional techniques and atonal styles. We will demonstrate how the original teaching music was adapted to incorporate a diverse soundscape.

Music and Storytelling: Developing Imagination through the Use of AI is an innovative workshop series designed to introduce young children to the narrative qualities in classical music through the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI). Our mission is to allow the endless imaginations of children to take form through musical stories created in real-time. Up until this point, we have tailored our workshops to the individual needs of various music centers, primary schools, and notably, children’s hospitals. The next phase involves refining our strategy to enhance the immersive experience for diverse demographic groups, while also examining the possibilities for fostering AI literacy through music workshops. This workshop series embraces a technology-driven approach to bridge the gap between abstract concepts and tangible outcomes. By combining music, storytelling, and AI, we offer a unique and innovative educational experience that not only teaches children about the arts but also ignites their wanting to engage with AI technologies.

Mélanie Hélène Bonis (1858-1937) distinguished herself as a fine pianist and composer, publishing over 150 works for solo piano. To navigate the societal challenges faced by women in the French haute bourgeoisie, she published her compositions under the abbreviated name ‘Mel’. Influenced by Chabrier, Chausson, and Debussy—fellow students at the Paris Conservatoire—her compositional style exhibits a unique blend of their influences. Bonis infused her works with a distinctive approach to rhythm, harmony, tone color, revealing a playful sense to her compositions. This presentation invites the audience on an enchanting exploration of Mel Bonis’ lesser-known gem, “Album pour let Tout-Petits, Op. 103.” Comprising a collection of charming solo piano pieces, this album is a musical treasure trove designed for the early intermediate pianist (Level 3-5). Dive into the whimsical world of this unknown Album for the Young as we unravel the delightful narratives encapsulated in Bonis’ miniatures.

Khanh Nhi Luong (Michigan), Le Binh Anh Nguyen (Cincinnati), Jasmine Wong (Michigan)

University of Cincinnati / University of Michigan; John Ellis, faculty mentor

Lizzie French, Sharon Hui

University of Colorado Boulder; Jennifer Hayghe, faculty mentor

Congratulations to all participants and applicants! We look forward to highlighting the outstanding work of pedagogy and collegiate groups and to foster global community engagement among our collegiate cohorts and faculty. Learn more and register by clicking here.

We would like to thank Sara Ernst for this article about our 2024 Summer Intensive Seminars. Interested in learning more about our 2024 Summer Intensive Seminars? Learn more by clicking here.

We are offering two summer seminars in the month of July: An International Exploration of Piano Teaching Literature on Monday-Tuesday, July 8-9, and Teaching Elementary Pianists on Friday-Saturday, July 12-13. In the first seminar, learn about world cultures and great repertoire for the teaching studio. The second seminar offers an overview of best teaching practices for working with young piano learners. Both seminars will jump-start your fall planning through new ideas for repertoire and curricular principles for elementary pianists.

International Exploration of Teaching Literature is led by Leah Claiborne and Luis Sanchez, with presentations and panels by guest speakers Gulimina Mahamuti, J. P. Murphy, William Chapman Nyaho, and Omar Roy. Teaching Elementary Pianists is led by Sara Ernst with presentations, demonstrations, and panels presented by Marvin Blickenstaff, Scott Donald, Judith Jain, Andrea McAlister, Rebecca Pennington, Craig Sale, and Janet Tschida.

Session leaders and guest presenters have structured the seminar program to include discussion and dialogue. There is purposeful time planned for the application of principles, collective brainstorming, asking questions, and sharing personal experiences and ideas.

No travel required and no extra cost for accommodations. These real-time, interactive seminars can be joined from the comfort of your home (or summer home!) and will be held over Zoom. Early bird registration is just $275, discounted registration for subscribers is $249, and discounted student registration is $175. Regardless of your location, it is easy to join us online!

Each day of the seminar runs from 12:00 PM EDT and concludes at 5:00 PM EDT, with short, programmed breaks throughout the five-hour time block. This real-time program is available across many time zones!

Join us! Register today to secure your early-bird registration at https://pianoinspires.com/summerseminars/.

We would like to thank Carla Salas-Ruiz for this contribution on writing articles for research publications such as the Journal of Piano Research. Learn more about the Journal of Piano Research by clicking here.

Writing, akin to music, provides a platform for self-expression. It also fosters critical thinking and enables us to articulate diverse perspectives, integrate information, and contribute to the advancement of our discipline. Yet, it’s common for many of us to feel a bit lost, unsure of where to even start. Have you ever found yourself facing a blank page, unsure of what to write or how to transform your project or research study into a compelling and engaging work? I have experienced this scenario several times. However, it wasn’t until I drew parallels between piano practice, lesson planning, and writing that a breakthrough occurred. I am excited to share these connections and encourage you to view academic writing as an art form for which you already possess all the necessary tools. Now is the time to leverage these tools and recognize writing as a creative exploration, where intentional choices and practice yield inspiring outcomes, similar to performing a piece or teaching a lesson.

When practicing any musical piece, it’s crucial to grasp the composer’s expressive ideas and the essence of the composition to shape the interpretation effectively. To do this, we listen to recordings from other performers and study the musical language of the composer throughout their repertoire. Similarly, in writing, the initial step involves gathering exemplary articles from various sources such as journals, magazines, books, and other publications to identify essential elements like structure, language usage, and coherence. Deconstructing these articles, akin to dissecting a musical composition into sections and phrases, facilitates targeted writing practice. Analyzing the author’s intentions behind effective writing serves as a guide in crafting our roadmap. Additionally, extensive reading enriches our understanding and fuels creativity by exposing us to diverse viewpoints and encouraging critical thinking.

Having learned from the insights of fellow writers, now is the ideal time to establish a method. This is similar to creating a practice log, focused solely on the concepts pertinent to your topic. During this phase, your reading should be targeted towards understanding existing discussions relevant to your chosen idea. It is essential to adopt a systematic approach, meticulously extracting key concepts from authors and documenting them methodically. I recommend constructing a table with columns for the source, author’s name, key quotes, year of publication, and page numbers.

After completing your reading journey, it is crucial to define your idea or research question through discussions with peers, similar to seeking feedback on a musical composition. Sharing your ideas with others can be tremendously beneficial, as they serve as a sounding board, potentially providing invaluable clarity to your thoughts. For instance, during my time in graduate school, my focus was on studying motivation. However, given the extensive literature surrounding the concept, it was only upon encountering the theory of Interest Development1 that I could delineate the scope of my idea and purposefully devise a roadmap to satisfy my curiosity. This process was greatly facilitated by continual discussions with colleagues, friends, and professors.

With our ideas taking shape, we transition into methodological design, akin to selecting the appropriate techniques for musical expression. This time is about crafting a research question and defining a plan to answer that question. Establishing a robust research question is imperative, as it serves as a guiding beacon amidst the myriad of available methodologies, including quantitative, qualitative, ethnographic, historical, and/or philosophical approaches. Developing a method involves meticulously outlining the research design, methods, and techniques employed to satisfy your curiosity. It will outline your plans for data collection and analysis. In an academic context, this comprehensive plan encompasses critical decisions about how we chose participants or composers we’ll study, what tools we will use to gather information, how we will analyze that information carefully, and what conclusions we will draw from it. We will also look closely at what the findings mean and how they add to what we already know, the ideas we are working with, and how they can be useful in our field. This thorough analysis involves looking at the results in connection with the questions we asked at the start and the big ideas we are exploring, while also thinking about what they might mean for other important areas. Collaboration could be key in this step. Just as we gather to play beautiful chamber music, collaborate with colleagues that may have additional knowledge in this area, approach them and develop your idea in a multidisciplinary way.

Creating an outline for presenting your writing is essential to maintain clarity and coherence throughout your work. Remember Step 1? This is where your grasp of writing structures and tendencies becomes invaluable in organizing your writing process effectively. Consider these questions to initiate an initial outline:

Ensure you iterate through several drafts and seek feedback from peers and mentors. Crafting a roadmap for written contributions ensures that our ideas are effectively communicated with clarity and impact, much like crafting engaging lesson plans or conducting focused practice sessions. Once you feel confident with your outline, begin writing without self-judgment; allow yourself to simply type! Stick to your outline, but don’t hesitate to make adjustments for better flow if needed. Much like practicing an instrument, this stage represents full engagement in practice: experimenting with specific strategies and refining particular sections.

Just as we can sense when our repertoire is ready for the stage, we also know when our written work is prepared to be shared. Whether through academic journals, book chapters, or magazines, sharing our work enhances communication skills, professional growth, and advances our field. Similar to selecting the ideal venue and format for a recital, deciding where to publish prompts us to find platforms where our contributions align well. After completing our written work and reflecting on “Step 1,” we can determine which journal or magazine best suits our work. There are research-specific journals as well as those catering to practitioners. Understanding the purpose of each publication can assist us in making this decision. In the music field, there are a number of journals, including Piano Magazine and the recently launched Journal of Piano Research. We should consider all options, and after reviewing previous research, we can gauge the expected contributions and target audience.

Recognizing writing as an art form encourages us to engage in a journey of creativity and purposeful expression. Through the process of exploration, refinement, and sharing, we achieve transformative musical and teaching outcomes. Just as musical performance brings compositions to life, as writers we can give vitality and resonance to our ideas, enriching our collective discourse and advancing our field.

Go to journalofpianoresearch.org/ to learn more about this new publication!

MORE ON RESEARCH

We would like to thank Jane Magrath for this insightful article. Want to learn more about teaching piano technique? Join us on Wednesday, April 17th at 11:00am ET for our latest webinar, Foundations on Technique, with Julie Hague and Alejandro Cremaschi, host. To learn more and register, click here.

The first years of piano study are critical ones for developing technique in the young student. The extent to which various elements of playing are developed in the early years should be greatly expanded.

Central to the development of technique in the very first year is the establishment of a good hand position and the establishment of the ability to move freely about the keyboard. Equally important is the development of control of the large playing units-upper arm, forearm, and wrist-then moving to the smaller units in the hand.

How should these principles for the first year be extended over several years of piano study? Surely proficient technique involves most importantly the ability to control sound and tone as well as the ability to move quickly. The establishment of a proficient technique also involves the ability to playa series of patterns commonly found in piano music in a variety of combinations. Pianists at all levels concentrate heavily on the playing of scales, arpeggios, and chords (as well as double notes, octaves, trills and so on).

What do we teach, then, in the early years? Many teachers begin to prepare students to play scales using five-finger pattern exercises played in all keys. Some also use selections from,a wealth of classical etudes that rely heavily on passagework for developing finger facility in scale passages. The playing of arpeggios is often first prepared by the playing of broken chord patterns in hand-over-hand fashion. Other miscellaneous aspects of technique essential at this level, such as expansions-contractions of the hand, are taught through teacher-devised exercises or through various technique books.

Unfortunately, it seems rare for many students in the second through fourth years to extend chord playing beyond the playing of the common-I N6/4 I V6/5 I-chord activity in various keys. Chord inversions, for example, both blocked and broken, need to be carefully prepared and presented to students. The playing of triads up and down the keyboard (in the various registers) with facility is essential. Students need to practice, even at the earliest levels, voicing chords in various ways-balancing between the hands, of course, but also voicing the various notes of a chord within a hand for projection. Students should learn to play various chords and inversions after a bass octave to prepare for the “oom-pah-pah” accompaniments of many pieces in the intermediate repertoire. Finally, students need to experience the shape and feel of dominant and diminished seventh chords in all positions, and develop a natural feeling for these chords that become so important in intermediate literature. The facile playing of chords is an essential and often-overIooked aspect of playing.

All in all, we focus well on the what that is taught for technique (such as which chord patterns or which scale patterns or which etude books are used). Should we not be focusing more on how the technique is taught? At all levels, goals for technical concepts should concern quality of sound, the focus on the correct hand position and use of the fingers, the production of sound from the correct source, the correct physical motion in moving to a chord, and so on. To achieve a fully developed technique, it is essential that the pedagogical focus be primarily on how the sounds and gestures are produced and on listening perceptively to evaluate success. Technical development is most effectively, but not exclusively, transmitted through meaningful hands-on experience: private and group piano lessons, participation in and observation of master classes, observation of video tapes and live performances, analysis and listening in individual practice, and through observation/trial at workshops. (Recall how difficult it is to read a technique book on physical gestures.)

We hope you enjoyed this excerpt about Jane Magrath’s approach to technique for beginning and intermediate students. Read the full article including additional thoughts by Scott McBride Smith, Miyoko Nakaya Lotto, and Louise Savage by clicking here.

MORE ON TECHNIQUE

We would like to thank Scott Donald for this tribute to his teacher, Marvin Blickenstaff. As we continue the season of gratitude and giving, we pay tribute to piano teachers from around the country who are transforming the lives of their students. Students, parents, and colleagues are honoring piano teachers from their communities as part of the “Power of a Piano Teacher” campaign. We welcome you to celebrate your own teacher by sharing a tribute with us and donating to The Frances Clark Center.

I often tell people that when I grow up, I want to be like Marvin Blickenstaff. My journey with Marvin started in 1999, when we both arrived at the New School for Music Study. During my time there, I had the opportunity to teach, perform, and most importantly, learn from Marvin. His artistry as a teacher and performer is undeniable, but Marvin’s most endearing quality is his humility and the way he challenges us all to be better teachers.

During my tenure at NSMS, I was presenting a solo recital and after a series of miserable performances, I really had doubts about my playing. Marvin told me a story of a recital that he played years before in which he wrote across the program – Fin. I was touched by his openness about his own doubts and willingness to share. As I thought about that conversation with Marvin and how he managed to overcome some of those doubts and fears, I decided to challenge myself to do the same. His sage advice helped me get past that dark period in my performing life.

Another incredible characteristic about Marvin is his ability and desire to work with students of any level. Marvin is perfectly comfortable working with a young child on “Engine Engine #9” and then spend the next lesson working with an advanced student on Ravel! As a faculty member at NSMS, I was able to observe him working with my students that were in the advanced program. There were so many things that I learned about repertoire, technique, and developing musicianship through those observations. I wouldn’t trade that for anything!

We no longer teach together but I still hear his voice and his wisdom when I continue to teach my students at my own studio. In fact, as I write this tribute, I have a student working on Grieg’s Notturno. My approach to that piece has Marvin written all over it! I am forever grateful for the friendship and wisdom I gained through our time together. Marvin has made an indelible impression on my life and teaching.

In 2023, the Frances Clark Center established the Marvin Blickenstaff Institute for Teaching Excellence in honor of his legacy as a pedagogue. This division of The Frances Clark Center encompasses inclusive teaching programs, teacher education, courses, performance, advocacy, publications, research, and resources that support excellence in piano teaching and learning. To learn more about the Institute, please visit this page.

We extend a heartfelt invitation to join us in commemorating Marvin Blickenstaff’s remarkable contributions by making a donation in his honor. Your generous contribution will help us continue his inspiring work and uphold the standards of excellence in piano teaching and learning for generations to come. To make a meaningful contribution, please visit our donation page today. Thank you for being a part of this legacy.

MORE ON THE POWER OF A PIANO TEACHER