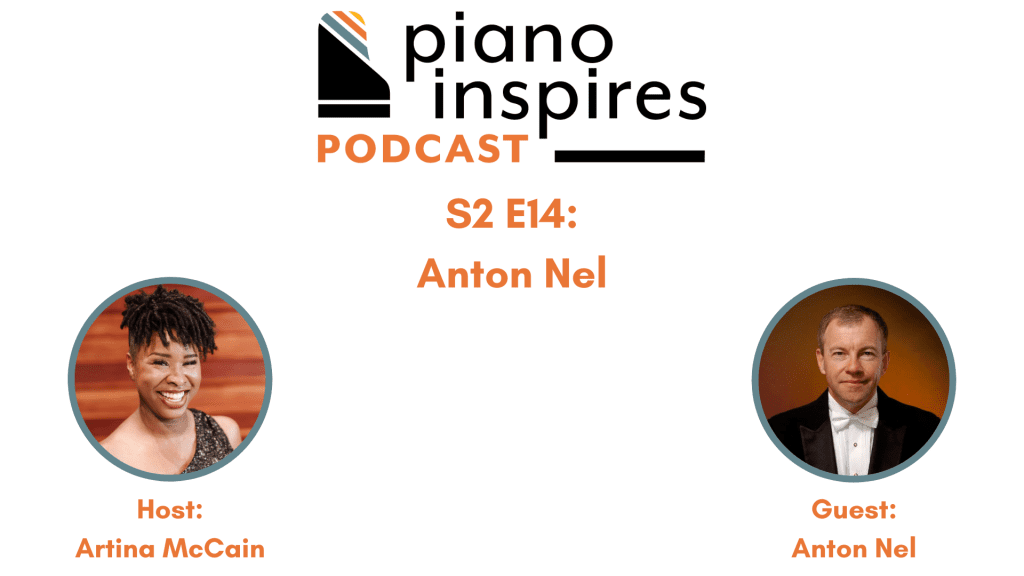

To celebrate the latest episode of the Piano Inspires Podcast featuring Anton Nel, we are sharing an excerpted transcript of his conversation with Artina McCain. Want to learn more about Nel? Check out the latest installment of the Piano Inspires Podcast. To learn more, visit pianoinspires.com. Listen to our latest episode with Chee on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or our website!

Artina McCain: What inspired you to make the switch from piano to fortepiano or harpsichord? I happen to know you have these at your house too.

Anton Nel: My place looks like a museum now. The first wonderful teacher I had when I lived on the farm, the man who started me really, he was—again, you know, you think back of these days and how wonderful these people were. I had never seen a harpsichord before or anything, but he had records of this instrument that this music was written for, and so he made cassette tapes of his records for me of the Bach harpsichord concertos and all this stuff. I was mesmerized by the sound of it, and just loved it.

Then I played on one of my earliest concerts. We went to Johannesburg. I was playing, I think, the Kabalevsky Third [Piano] Concerto on this program with other young people. You win these concerto competitions, right, and then you play in these concerts. The first piece on the concert was the Bach Concerto for Four Harpsichords. It’s the thing that’s like the Vivaldi Four Violin Concerto. Well, I had never seen a harpsichord before. I think I was maybe 13 or 14. My mother was beside herself. I had absolutely lost all interest in the piece that I was playing. I wanted to play on those harpsichords, and of course, and I caused such a consternation. And of course, everything was fine, you know, but then I subsequently got a small Italian single-manual instrument of my own. So I started to play when I was 15 or so, the harpsichord, and I played through school, and I also like the organ and so on.

The fortepiano—there’s a wonderful man in Austin whose name is Keith Womer, and he has a period instrument orchestra called La Follia. He had this idea that I would possibly take to playing the fortepiano. About ten years ago, he called me and offered me an opportunity to play a Mozart and a Haydn concerto with the orchestra. It was like a miracle that happened. I took this instrument and I absolutely loved it, and started to really learn it. And then suddenly, all of these things that I puzzled about for so many years—the articulations in Mozart, the dynamic markings, all this finicky stuff that on the modern piano is so tricky to negotiate—suddenly became second nature. So I really, really worked at it. Then, I brought my harpsichord playing back as well. So about a quarter of my engagements now I play these instruments, and it has opened my ears in ways I couldn’t even imagine. I always thought that I listened pretty well, but—and my students—this was a little bit before your time. I think my students now always know when I have a harpsichord or fortepiano concert coming up because I’m impossible. No slur is right, no articulation is right. I get all sort of OCD and persnickety and sort of fussy—I’m always a little difficult. So you talk of inspirations—that has made a big, big difference. It sort of added a new dimension to me as a musician, so that makes me happy. So, yes, playing that annually is always an adventure. I’ve learned so much new music too because of it.

AM: So do you now teach some of that to your students too? Do you have them over and they play it?

AN: I do sometimes. If I ever have a little bit more time in my schedule, I would like to teach a sort of a basic class. I’m not sure I would be qualified to actually teach anybody to play the instruments as a major. I don’t think my knowledge is quite—I’m not quite ready for it, but absolutely the basics I can. I think it’s important for pianists to know these things. Even if they don’t play them seriously, just to have the opportunity to try them, because it’s initially quite shocking. Still, when I go—I just had to play a fortepiano program the other day—you go to it, and for the first two or three hours on the instrument, if you’ve not played it for a while, you sound so bad. Oh, you sound so [bad] because you keep wanting to—and for those things, you have to let the instrument play you. You must not play it. You let it. It’ll show you, if you let it. But if you sort of take out your Rachmaninoff Third [Piano] Concerto chops, it’s not going to work.

AM: Definitely not.

AN: But, we all have tendencies, you know. So that’s awesome.

AM: Yeah, we don’t have enough opportunity to play period instruments as pianists. So that’s incredible that that’s a part of your engagements now, is to play those instruments.

AN: Yes, because, I mean, again, it’s something that becomes very specialized. The groups I play with are 100% authentic. I mean, last year I had this fabulous opportunity—I played the Beethoven Fourth [Piano] Concerto on an instrument from about 1809 with about a fifty piece all-original instrument orchestra. Even the clarinet[ist]s made their own instruments, so it’s something I’ll never forget as long as I live. I had to relearn the whole thing, of course, and the instruments still had knee pedals, just like my fortepiano at home, and also all his instructions about how to use the una corda and all this and in the slow movement. It was a transformative thing. I’ll never forget it.

AM: Wow.

If you enjoyed this excerpt from Piano Inspires Podcast’s latest episode, listen to the entire episode with Anton Nel on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or our website!

MORE ON ANTON NEL

- PIANO MAGAZINE ARTICLE: An Interview with Anton Nel by Stephen Pierce

- PIANO MAGAZINE ARTICLE: A Survival Manual for College Teachers by Michelle Conda and Erin Bennett

- PIANO MAGAZINE ARTICLE: DIGITAL-ONLY CONTENT: A conversation with Pamela Mia Paul, pre-screening jurist for the 2017 Cliburn Competition by Deborah Rambo Sinn