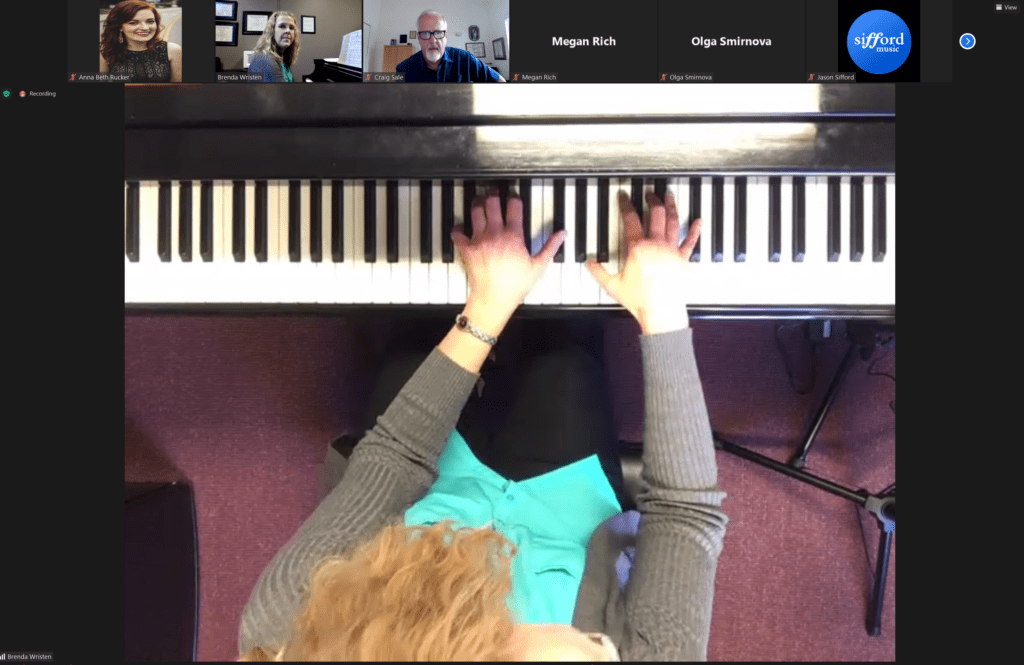

As we enter the season of gratitude and giving, we pay tribute to piano teachers from around the country who are transforming the lives of their students. From Massachusetts to Hawaii, students, parents, and colleagues are honoring piano teachers from their communities as part of the “Power of a Piano Teacher” campaign.

The teachers featured here are making profound contributions to students at all stages, from the youngest beginners, to college students, and to those who study later in life.

Paz Rivas honors Penny Lazarus from Newburyport, Massachusetts

Penny has been a blessing in my daughter’s life. Penny has helped her gain confidence and has created a sense of discipline, consistency, and fun in learning that was and continues to be so important to her right now. Last but not least, Penny is patient and kind, and my daughter loves learning how to play piano. Penny is so special, she approaches each lesson with such enthusiasm and passion after so many years of teaching (especially with the youngest students). We are grateful to have found her, and Newburyport is lucky to have her.

Merrie Skaggs honors Betty Todd Smith from Olathe, Kansas

Betty Todd Smith personifies the “Power of a Piano Teacher,” and I am delighted to recognize her. Betty has made a difference in my granddaughter Rylee’s life with Betty’s encouragement, finesse, knowledge base, and passion for piano. Rylee observed recently, “I may go into my piano lesson in a bad mood but I come out in a good mood.” The care and feeding of her soul that Rylee receives from Betty and piano have been immeasurable. Rylee is an active athlete and as she started high school this fall, I asked her if she planned to continue with piano throughout high school. She looked at me like I had two heads and said, “Of course, Granny!” I appreciate the positive impact that Betty and piano have made on Rylee’s life.

William Hughes honors Margaret Roby from Terre Haute, Indiana

Margy’s teaching career has been exemplary in every way. All of her students know she is interested in more than their piano progress. She is a nurturer by nature, and her students have always been devoted (as have their parents!). I have had the pleasure and privilege of working with students that she has sent to study with me. In every case, they had been expertly prepared and were a joy to work with—no “transfer repairs” necessary. She has been a leader in our local and state music teachers associations and is an inspiration to all of us.

All of her students know she is interested in more than their piano progress.

Daniel Tsukamoto honors Donald Zent from Wilmore, Kentucky

When I first met Dr. Zent at Asbury University, I noticed his sweetness and meekness, but I never realized how much he was going to change my way of performing piano. He demonstrated that I don’t need to play loudly all the time, and he gave me the liberty to select pieces that interested me. He was very compassionate when helping me find another way to memorize piano pieces besides listening. He was calm in demeanor and spent equal time with each of his students. I am thankful for his guidance during my student years at Asbury University.

Lloyd Lim honors Carolyn Stanton from Honolulu, Hawaii

Carolyn Stanton is my sixth piano teacher, and I made surprising progress over a five-year period. They say you can’t teach an old dog new tricks. Well, I’m an old dog, and I still learned a lot!

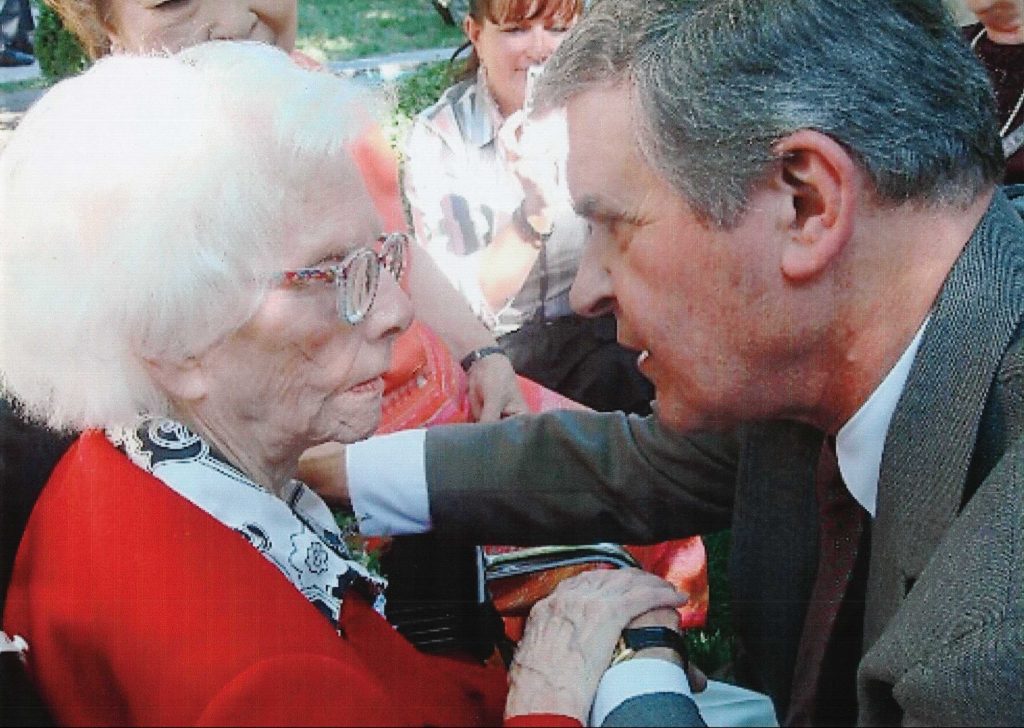

Madelyn’s inspiration helped to make my dream come true!

Sarah Roy honors Madelyn Trible from Lafayette, Louisiana

Madelyn was my first piano teacher as I began a bachelor’s degree program in vocal music education. After three years of lessons, she encouraged me to take a pedagogy class. I loved working with the two fifth-grade girls assigned to me that semester. Eleven years after that degree, I returned for three more years of lessons with Madelyn. Then I studied organ for three semesters, since I had a dream of playing in a church someday. I have been an organist in a small rural church since October 2013. Madelyn’s inspiration helped to make my dream come true!

Honor your teacher today by joining our “Power of a Piano Teacher” campaign.