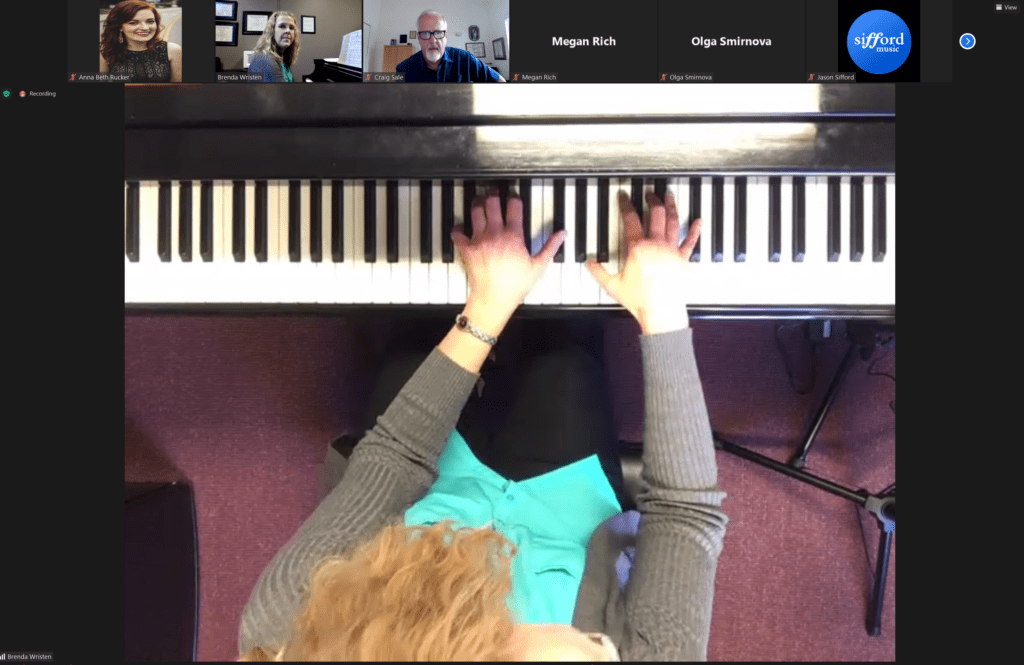

We were pleased to welcome Dr. Brenda Wristen, Professor of Piano and Piano Pedagogy at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and author of the Piano Magazine article “No Thumb or Fifth Finger on Black Keys, Except…” for an informative article discussion in September.

Dr. Wristen and Senior Editor Craig Sale explored the rules of the black keys, when the rules should be broken, and how to navigate playing fingers 1 and 5 on the black keys in a technically efficient and healthy manner. After an inspiring conversation with Brenda and Craig, we moved into small breakout rooms to discuss the topic with them both and other subscribers. It was a wonderful opportunity to explore our shared ideas on technical difficulties facing our students.

We welcome you to enjoy the short video excerpt below from this engaging session and encourage you to join us for our next subscriber discussion on October 27 at 11:00 am Eastern.

We will explore the music of Central and South America with Dr. Luis Sanchez and Ricardo de la Torre who will lead us in a conversation about repertoire by composers Manuel Ponce and Luis Gianneo. They will share excerpts from their Inspiring Artistry video modules and engage in discussion with attendees. Come ready to share, discover, and learn in this lively and educational event! Register here.

You can read Dr. Wristen’s full article here and in the print version of Piano Magazine Autumn 2022.

Video Transcription

Sale: . . .summarize this unwritten fingering rule about the thumb or the fifth finger on black keys, and maybe start with how that does serve a purpose, where did it ever come from? And then you might want to move into how that works and how it doesn’t work, and why it doesn’t work sometimes.

Wristen: Well, actually, it is a written rule. And it comes from Czerny, like many of our premises regarding fingering, in his second volume of theoretical and practical piano forte school, was published around 1839. Now, again, I’m not sure that so much his rule is a rule that had come into common practice. And, he was just codifying it and writing it down for the rest of us. But, he laid out three fundamental fingering premises at the beginning of that volume, one of which was the thumb and the little finger should never be placed on the black keys in playing the scales. The other two was that 234 and 5 needed to be used, that they couldn’t be passed over one another, and that the same finger should not be placed on two consecutive notes in case you’re interested.

But, with regard to the no thumb or fifth finger on black rule premise that he laid out, Czerny himself went on to suggest that there were many exceptions to the rule. In fact, to all three of the rules, I’m going to quote here, I wrote this down, he said, “Every passage which may be taken in several ways, should be played in that manner, which is the most suitable and natural to the case that occurs, and which is determined partly by adjacent notes, and partly by the style of execution.”

So I think a discerning reading of Czerny really demonstrates his flexibility in adapting a fingering choice based on a musical context. And this is a real life example, I have seen this. That is something that I have seen. And obviously, that is not a great fit for the hand. I think there’s also a utility in a progression like that were primary chord progression in closest position or cadences to simply learning the shape. And getting that in that hand fluently. So that is an instance where we would use thumbs and fives on black keys pretty much right away.

Now as to your question, Craig. Yes, that can be an issue navigating those shapes, particularly depending on hand size. So basically, the way we deal with those shorter fingers– if you notice what I did there in A major. You see what I’m doing slightly with my wrist, and my arm angle, it’s maybe not quite so visible there. Let’s do it in this octave [instead]. So I simply make sure that I’m getting my arm aligned, and I’m also moving up into the black key, that is going to involve my moving my arm forward, but that’s okay, because I have time to do it in the context of chord playing.

Sale: And Brenda, that example, particularly in your left hand in that key was is a beautiful visual of keeping the thumb in line with the arm, which I really appreciate seeing that, especially at that center part of the keyboard. This is essential to do if it was lower, you can be in on the keys further, as it is.

Wristen: And it is is radically different: the angles that we need to employ from one register to the next. You know, honestly, with my piano majors, that is one of the fundamental reasons I teach scales and arpeggios. Specifically, because we do four octave scales and arpeggios, it feels radically different from one octave to the next, the same key and I want to lead them to that discovery and lead them to that intuitive understanding. It’s not really intuitive because I asked guided questions about it to draw your attention to how the angles are working there between their finger and their arm.