Piano Inspires Podcast welcomes Vanessa Cornett with Alejandro Cremaschi as she discusses mindfulness and anxiety management for ourselves and our students.

Podcast: Play in new window

Piano Inspires Podcast welcomes Vanessa Cornett with Alejandro Cremaschi as she discusses mindfulness and anxiety management for ourselves and our students.

Podcast: Play in new window

To celebrate the latest episode of Piano Inspires Podcast featuring Vanessa Cornett, we are sharing an excerpted transcript of her conversation with Alejandro Cremaschi. Want to learn more about Cornett? Check out the latest installment of the Piano Inspires Podcast. To learn more, visit pianoinspires.com. Listen to our latest episode with Cornett on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or our website!

Alejandro Cremaschi: It’s interesting because we are talking about anxiety, but there’s this other side of what you do, which is about peak performance and using sports psychology tools to help. I think in some ways they are related, right? Peak performance and anxiety?

Vanessa Cornett: They are! This is going to be an oversimplification, but I think musicians are behind athletes significantly. I think elite athletes and their coaches and their sports psychologists have understood for many decades, that if you train the mind for peak performance, that helps automatically with the anxiety because you’re taking a proactive approach. You’re thinking, “How do I win? How do I be the best? How do I get the gold?” You have practiced all of these internal and external things to get there. Okay, what do musicians do? We spend hours and hours training the body in our practice room and when we feel anxious, first of all, it feels wrong. “I shouldn’t be feeling this, this, clearly, I’m doing something wrong.” Then what we do as musicians is we tend to take a reactive approach: “Oh, you have this problem. Let’s see how we can help you fix this problem and get over it.” What I tell my students, is if you go into a bookstore or search on Amazon for “performance anxiety management techniques for top athletes,” “stage fright for football players,” you don’t find those books. You don’t find—Michael Phelps is not writing a book on: “I was Scared and Here’s How I Got Over It.” Because all of the literature is: “What can I do to be the best? What can I do to put my mind in the game where it needs to be?” I really believe—and again, it’s an oversimplification, because music and sports aren’t the same—but if we musicians would take a more proactive approach, if we would help our students and ourselves think differently, or pay attention to our mental processes, I don’t think performance anxiety would go away but I think we would know how to proactively sort of deal with it and it wouldn’t be weird, it would be normal. It would be you know that adrenaline when we feel scared—that’s the same adrenaline when we’re having a peak performance experience. I tell my students, no world record at the Olympics was ever broken except in front of an audience. Those are when the world records are broken because there’s so much adrenaline and it’s funneled in a certain way, right? So why can’t musicians take that adrenaline and instead of recognizing it as dread—”I’m going to die!”—why can’t we get our mind in a place where we use that as fuel as best we can to have what we would call a peak performance experience?

If you enjoyed this excerpt from Piano Inspires Podcast’s latest episode, listen to the entire episode with Vanessa Cornett on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or our website!

MORE ON PERFORMANCE ANXIETY

We would like to thank Lynn Worcester Jones for this insightful article on teaching Alexina Louie’s Star Light, Star Bright. Want to learn more about music by women composers? Check out our course, Hidden Gems: Four Centuries of Piano Music by Women Composers. Learn more and enroll here.

Introducing intermediate piano students to twentieth-and twenty-first-century compositional techniques and styles is essential, especially as we move from Gen Z students to those in Generation Alpha (born in the early 2010s). In Star Light, Star Bright (1995),1 both generations will find an established, musically rich collection of nine pedagogical solo piano pieces tailored for this purpose by Alexina Louie,2 an internationally recognized, living female composer. Students will gain greater rhythmic control, perceive their sound differently, explore new freedoms in their technique, and appreciate the importance of score study. Effective performance of these techniques will build a student’s inner conductor as they absorb the importance of rhythmic values and new approaches to time and space. Beyond the pedagogical benefits, these pieces may also help teachers retain students who are resistant to, or need a break from, traditional repertoire.

Star Light, Star Bright comfortably and brilliantly engages the intermediate-level student with minimalism, frequent meter changes, unmeasured music, and new presentations of musical notation. The pieces sound sophisticated and advanced beyond their pianistic requirements, and alone or in combinations are excellent choices for study in lessons, recital performances, and competitions. One approach in teaching this set is to study and perform the pieces in pairs. Each piece is brief—two to four pages—with the right number of contemporary musical techniques, styles, and new challenges. Louie provides musical directions that are succinct, specific, and inviting for students new to the way these techniques sound, feel, and appear on the page; and students and teachers will appreciate her pedal markings, ample fingerings, tempo alterations, articulations, and dynamics in the music.

Eight out of the nine pieces are listed in The Royal Conservatory Piano Syllabus, 2015 edition (RCPS)3 and they offer Gen Alphas an opportunity to be intrigued by stars, planets, and galaxies as they explore new sounds and colors emanating from this celestial set.

“Distant Star”

“Distant Star” is one of the most accessible pieces to learn in this collection and is a seamless introduction to frequent meter changes in a contemporary style for the intermediate student. Pianists will discover eleven meter changes in this brief twenty-four-measure piece with the quarter note receiving the main beat throughout. “Distant Star” begins in the lower register of the piano with two bass clefs and does not move into the ledger lines above the treble clef until the last four measures. Pianists with small hands will find one manageable octave stretch on F sharp that appears three times in the left hand in a moderate tempo. There are open fourths and fifths and the extended chords set an expressive mood that produces an other-worldly atmosphere. “Distant Star” is listed as Level 6 in the RCPS, p. 54.

We hope you enjoyed this excerpt from Lynn Worcester Jones’s insightful article on teaching Alexina Louie’s Star Light, Star Bright. To read the full article, check out our course, Hidden Gems: Four Centuries of Piano Music by Women Composers. Learn more and enroll here.

Not yet a subscriber? Join for only $7.99/mo or $36/yr.

Today, we celebrate International Women’s Day, a time to honor and reflect upon the remarkable music and contributions of women. In this Discovery Page post, we have curated a collection of Piano Inspires resources to help everyone discover something new. From our international webinar series, to articles in Piano Magazine and Piano Inspires Kids, to our online course, Hidden Gems: Four Centuries of Music by Women Composers, there is so much to discover! We hope these resources will provide useful tips and ideas to help you incorporate music by women composers into your recital programs, lesson plans, and more.

Hidden Gems: Four Centuries of Piano Music by Women Composers is an online course designed to shed light on a fraction of the large breadth of works by talented women composers spanning four centuries. Sessions feature selected piano works at varying levels of difficulty (elementary to early advanced), surveyed from a pedagogical and performance perspective.

Course Co-Leaders: Dr. Annie Jeng, Dr. Susan Yang, Evan Hines, Dr. Brendan Jacklin, Dr. Clare Longendyke, and Ashlee Young.

Senior Editor: Craig Sale.

Recently I participated in a concert featuring works by women composers at the community college where I study piano. I am an amateur pianist but a historian by profession, and I was curious about the backgrounds of these long-neglected figures. So, along with preparing my musical selections, I also investigated the lives of the composers and the social and musical contexts in which they worked. Some of the composers I researched—Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel, Clara Wieck Schumann, Amy Beach—are practically household names. Others—Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre, Maria Szymanowska, Cécile Chaminade, Margaret Ruthven Lang—were successful in their own times but less prominent today. Still another—Clara Gottschalk Peterson—was obscure during her lifetime and remains almost completely unknown. All, however, deserve a place in both the performing and teaching repertoire.

Given the general lack of prominence of women composers, it is instructive to realize that while historically women were discouraged from pursuing music as a career, whether as performers or composers, that doesn’t mean that they didn’t make music. Quite the opposite, in fact. Example 1, a French fashion plate from 1835, shows two young ladies playing piano and singing in what looks like a domestic setting. It’s likely to be after dinner, and they’ve been asked to provide the evening’s entertainment. The singer is holding sheet music, not performing from memory, so they are probably sightreading (see Example 1).

In Autumn 2023, the Frances Clark Center launched a new initiative, Piano Inspires Kids, a magazine for young pianists developed by Editors-in-Chief Sara Ernst and Andrea McAlister. Through each quarterly issue, readers explore piano playing, composers, music from around the world, and music theory. The format is engaging and varied with listening guides, interviews, student submissions, music in the news, and games. The magazine includes an array of musical styles and genres, both from the past and present day. In addition, creative skills like improvisation, playing by ear, and composition are explored in step-by-step processes. Young pianists are directed to curated online content to deepen their engagement with the piano community.

The latest issue celebrates Florence Price. The issue includes a biography of Price along with an introduction to some of her piano works including the Piano Sonata in E Minor and her pedagogical piece The Goblin and the Mosquito. It also includes a short interview with pianist Karen Walwyn, a champion of Price’s music, along with new music composed by Artina McCain! To learn more, or to subscribe, go to kids.pianoinspires.com.

We would like to thank Leah Claiborne for this insightful article on handling repertoire that is culturally insensitive. This excerpted article comes from our new course, Piano Teaching through the Lens of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. The course is now available for presale purchase. Click here to learn more.

If you are taking this course, you are already demonstrating that you are dedicated and committed to creating inclusive and safe spaces for your students. Perhaps what I love most about inclusive pedagogy is that we all must be aware that creating a diverse studio will look different for every teacher, creating an equitable studio will look different for every teacher, and creating an inclusive studio will look different for every teacher. There is no one way to approach the best pedagogy practices through the lens of diversity, equity, and inclusion, but there are steps we all can take to make powerful changes in our music studios and communities.

Oftentimes, teachers say that they are committed to learning more about DEI efforts, but feel “stuck” with how to address culturally insensitive materials that arise in the educational resources that they are using. Below are three ways to potentially address these problematic issues to help teachers navigate what solutions might be best for them to incorporate.

Teach It?

When we approach musical material that is culturally insensitive, teachers still have agency to continue to teach the material. This course does not serve to “police” educators with what to teach and what not to teach. Rather, we aim to broaden awareness of the impact that the resources we give our students can have, and we provide alternative solutions and a path to help the student navigate an approach that best resonates with their practices.

One solution to consider is to continue to teach a piece even if there are insensitive materials found in the music. If this is the approach that a teacher wishes to take, there are still ways to create safe spaces around the teaching material if the teacher wants to continue to use the piece of music. The first steps for any approach is to take the opportunity to educate ourselves on the reasoning behind why the material could be offensive, racist, and/or culturally insensitive. By understanding the historical and social implications of these issues, we are better equipped to make an educated decision on how to handle these materials.

After further understanding is gained and a teacher still chooses to teach the music, I would suggest that a conversation around the cultural issues still takes place. This conversation will look different depending on the age and understanding of the student, but a dialogue can (and should) still be had. An example of this could be as short as,

“This is not a term we use anymore to refer to a group of people.”

“The lyrics to this music are not appropriate to sing because…. Would you like to create your own words next week?”

“This picture suggests ___ which is inappropriate. Would you like to draw a picture next week of what the music means to you?”

We hope you enjoyed this excerpt from Leah Claibornes’s article “So Now What?” from our new course, Piano Teaching through the Lens of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. The course is now available for presale purchase. Click here to learn more.

MORE ON DIVERSITY, EQUITY, AND INCLUSION

We would like to thank Trevor Thornton for this insightful article on The New School for Music Study’s Postgraduate Teaching Program. Want to learn more about the Postgraduate Teaching Program? Learn more and apply by clicking here.

The New School for Music Study’s postgraduate teaching program provides the opportunity to continue your education while serving as a junior member of the New School’s faculty. It is a ten-month period of intense teaching and learning that is sure to change your life. If you are finishing your master’s degree and want to pursue more training in piano pedagogy, I could give you a thousand reasons why to consider the postgraduate program at the New School, but I only have room for these six:

The New School’s postgraduate teaching program includes 15 hours of teaching each week in addition to observations and course work. That adds up to about 555 hours of teaching during the 37-week school year from the day after Labor Day through the third week in June. I like to joke that after I completed the program I could play the entire Music Tree series and most of the Celebration Series by memory. If you have not already worked with many beginning and intermediate pianists, you will feel confident in your abilities by the time you have finished the postgraduate program. If you already have significant teaching experience, you will be given the opportunity to push your teaching and lesson planning to an even higher level of excellence.

The New School’s connection to the Frances Clark Center and the National Conference on Keyboard Pedagogy (NCKP) provides many opportunities for postgraduate fellows to meet inspiring pianists and teachers working in the field. As a junior member of the faculty, you may be invited to participate in a faculty presentation at NCKP, which is a great way to put your best foot forward in front of teachers and faculty members from across the country. In addition to NCKP, you can also meet experts in the profession through the New School’s guest faculty residencies. In the program, you may get the opportunity to have a visiting faculty member observe your teaching and meet with you to give you feedback. Guest teachers also give presentations to the New School faculty on their areas of research, which can spark new ideas for your teaching or performing.

Your experience at the New School would not be complete without learning about the teaching of Frances Clark, Louis Goss, Elvina Pearce, Richard Chronister, and other founders of the New School. Frances Clark’s teaching philosophy still lives and breathes at the New School—There is music in every child and it’s the teacher’s job to find it and nurture it—We teach three things: Technique, Musicianship, Practice Habits—We teach first, the person; second, music; and third, the piano—Preparation, Presentation, Follow-Through—Sound, Feel, Sign, Name. If you are lucky, you will have conversations with members of the faculty who did their teacher training directly with Frances and Louise, and you will see the glimmer in their eyes as they describe how inspiring it was to be in their presence and to feel the gravity of how seriously they took our profession.

The faculty of the New School is the most inspiring group of people I have ever known. Each member of the faculty is intelligent, caring, diligent, industrious, creative, and so musical. One of the great joys and learning opportunities of the postgraduate teaching program is the time spent working closely with this team of experienced professionals who teach and play at a very high level. Each one can recommend teaching repertoire, lesson activities, helpful phrases, technique drills, organization tips, and anything else you need as you plan your lessons.

The New School celebrated its 60th anniversary in 2020. It has survived thanks to the vision and dedication of several leaders since Frances Clark’s passing, and it remains a fixture in the Princeton area. Through the postgraduate fellowship, you will not only learn the specific details of how to teach a well-planned lesson to a beginning piano student, you will also see the context that has been thoughtfully created in order to allow students to thrive. Before teaching at the New School, I taught in-home piano lessons, so I was keenly aware that the context of the New School—the group classes, Parents’ Observation Week, Parents’ Classes, Piano Progressions exams, Composition Contest, Recitals—hooked students and pulled them towards success in their studies. I know that wherever I teach in the future, I will be mindful of how it felt to teach at the New School and how I imagine it felt for my students. At the New School, excellence goes without question.

I applied to the postgraduate program because my friend had applied before me, but I never could have imagined the way the New School would impact the course of my life. I have had multiple conversations with people who have done teacher training at the New School, and many of us share the sense that the New School will never get out of our blood. I did my teacher training from 2018-2020, and after teaching at the New School for another two years, I joined the faculty of Tennessee State University, an HBCU in my hometown of Nashville, Tennessee. I do not think I would have been offered my current position without the teaching and performance experience that I gained at the New School. I have known other former graduates who have remained on faculty at the New School, gone on to pursue more education and college teaching, or moved to their city of choice and made a career by teaching independently, at a community music school, or at a college. No matter what choices you make after the postgraduate program, your thread will be woven into the tapestry of the New School, and you will forever have your experience of what quality music education at the piano feels like, inside and out.

Learn more about teaching and professional development opportunities at The New School for Music Study by clicking here.

MORE ON THE NEW SCHOOL FOR MUSIC STUDY

We would like to thank Chee-Hwa Tan for this insightful article on creative activities to explore with your students. Want to apply these tips with your students? We encourage your students to submit to the Piano Inspires Kids 2024 Composition Contest. Student applicants are tasked with composing a fanfare inspired by the upcoming 2024 Summer Olympics. Learn more here: https://kids.pianoinspires.com/composition-contest/.

The ability to experiment and create with our instrument is an important part of piano study. Yet I would venture that for many of us who teach, this component of piano study presents a logistical challenge as we juggle the many aspects of music study. We may feel defeated at our inability to include creative activities like ear training, improvisation, transposition, musical composition, and analysis within lesson time, experience an existential crisis at the prospect of teaching what we did not ourselves learn, or feel overwhelmed about plowing through stacks of resources purchased at a workshop. On the other hand, when we do include these activities, perhaps our student freezes like a “deer in the headlights” when asked to improvise or create. If any of these scenarios are relatable, you are in good company.

This article will explore how we can use repertoire assignments to integrate experimentation and creation into regular lessons. Repertoire study is a staple of every lesson; assigning pieces that meet performance study needs, and that also serve as inspiration for creative assignments, is a way to meet both goals in a sustainable manner. This approach can be utilized during summers, several times a year, every other month, or with alternating pieces.

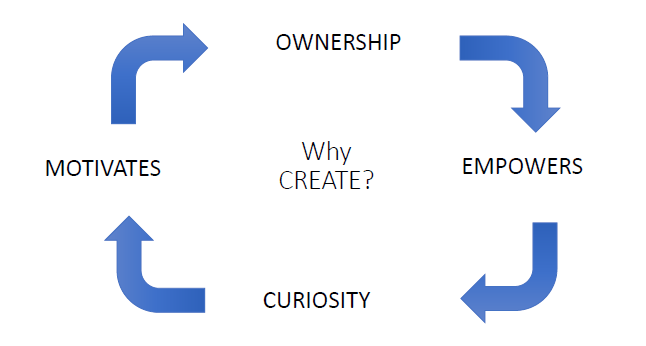

I will address this topic from the following framework:

Our teaching philosophy states WHY we teach and WHAT is important to us in our teaching. A teaching philosophy serves as a compass—a “priority check” for us when we feel overwhelmed by all the teaching to-dos and performance deadlines. As educators, it is good to revisit our teaching philosophy periodically to allow for personal growth and adjustments. Here, I share here my personal teaching philosophy:

I teach…

As teachers, we imprint a “feeling“—a feeling about the student’s identity in relationship to their music study. Long after formal lessons have ended, our students may not remember much of what they learned or even how to play what they learned, but they will remember how they felt in their lessons. This feeling will spur them to continue to pursue music in some shape or form, or this feeling will cause them to be afraid to try because they feel they are “not good enough” to meet the standards or expectations. Reviewing my teaching philosophy helps me to remember to prioritize the emotional connection with my student and the music making process and then to ask myself: What skills do I want my student to still have twenty to thirty years from now?

A lot of what we do as teachers focuses on the “what” and the “how”—specific skills for teaching repertoire and technique, materials, how to practice, style and interpretation, pedaling, theoretical knowledge—the list goes on. However, far more important than this is teaching the “why?” Do our students know the overarching purpose behind the concepts and skills that we teach them? Are they able to take what they learn in their music and apply it for their own purposes? Students who can do this are students who will make music for the rest of their lives.

If we have not experienced this type of process ourselves, this can be intimidating. The underlying philosophy is to nurture a sense of wonder and curiosity about this amazing process we call music. From the very beginning of piano study, slow down and reinforce theory and musical concepts by helping the student discover or identify the sounds in each of the pieces they study. Then, experiment with at least one of these concepts through listening and explorative play with the student.

If you enjoyed this excerpt from Chee-Hwa Tan’s article “Create to Motivate: Using Repertoire to Incorporate Creativity in Lessons,” you can read more here: https://pianoinspires.com/article/create-to-motivate-using-repertoire-to-incorporate-creativity-in-lessons/.

MORE ON PRACTICING

Chee-Hwa Tan has served as the Head of Piano Pedagogy at the University of Denver Lamont School of Music, as well as on the piano pedagogy faculties at the Oberlin Conservatory and Southern Methodist University. Ms. Tan is the author of internationally acclaimed A Child’s Garden of Verses and other piano collections. Her music is published by Piano Safari; with selections included in the Repertoire and Study series of the Royal Conservatory of Music, Canada, and the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music, London.

Join William Chapman Nyaho with Jennifer Snow for our next Piano Inspires Podcast as they discuss Chapman Nyaho’s rich musical history and his thoughts about the place of music in the world.

Podcast: Play in new window

To celebrate the latest episode of Piano Inspires Podcast featuring William Chapman Nyaho, we are sharing an excerpted transcript of his conversation with Jennifer Snow. Want to learn more about Nyaho? Check out the latest installment of the Piano Inspires Podcast. To learn more, visit pianoinspires.com. Listen to our latest episode with Nyaho on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or our website!

Jennifer Snow: I’d love for you to talk a little bit about how the collection [Piano Music of Africa and the African Diaspora, five volumes, Oxford University Press] came about, and how that all connected on that wonderful theme of generosity and service.

William Chapman Nyaho: Well, yeah, so that particular project started in 2001. I was doing a session for MTNA in Cincinnati and I had taken a leave of absence from the university that I was at in Louisiana. I was on Vashon Island in Washington.

JS: Lovely!

WCN: And I had, you know, been able to amass all these scores, out of print or manuscripts, of composers of African descent. So I did a presentation “Into Africa: Advocating Piano Music of Africa and the African Diaspora.” Luckily, Oxford University Press was at my presentation, and so they took me on, and that’s how it all started up in 2000. No it was 2002.

JS: How have you seen things change since 2002 when you published that extraordinary collection?

WCN: Honestly, I really think things have really started happening. Like, the concert last night Piano Stories [On Stage]. Somebody was saying, “Just look at the repertoire. I think this is the new norm.”

JS: Right?

WCN: You know it wasn’t, you know—

JS: Special presentation on this repertoire, it was just part of the canon.

WCN: It was just—exactly. Yeah, it’s part of the canon, no longer the “old faithfuls.” You know, yes, we did have Bach and that was just phenomenal. But, you know, it just made everything so important and just as special as Bach, you know. So I really see there’s been a huge change since I would say the publications, but probably even more so, during the time that we were locked up with COVID and we saw the death of George Floyd. You know, I mean, that was, I think—when people had to see that played over and over and over again—I think it was like a moment where, “Oh, wait a minute. Let’s stop and think about this.” You know.

JS: And the juxtaposition of, as a world we’re all together facing this horrible thing, and then something so horrific—

WCN: Horrific.

JS: It was, like the extreme juxtaposition of what we thought we were being as a human race, and what we are.

WCN: Exactly, you know, so I really think—and so, luckily, I would say, maybe those who had these books for several years, and were working or teaching them suddenly realized how important the work was. And for people to start understanding that, yes, we are diverse, and we need to celebrate our diversity, and promote equity and create access. And so it’s just been wonderful hearing Korean piano music, hearing music by, you know, people from the Philippines, you know, all this amazing music is now getting—people are hearing it.

JS: And it’s that kind of connection you speak about of, if you play the music from my country, you begin to understand who I am.

WCN: It’s correct.

JS: Cultural ambassadorship through music.

If you enjoyed this excerpt from Piano Inspires Podcast’s latest episode, listen to the entire episode with Nyaho on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or our website! Hear more from Nyaho at the 2024 Summer Intensive Seminar: An International Exploration of Piano Teaching Literature. Learn more here.

MORE ON WILLIAM CHAPMAN NYAHO

We would like to thank Sara Ernst for participating in this interview answering questions about effectively teaching young students. Interested in learning more from Sara Ernst about teaching elementary pianists? Attend our 2024 Summer Intensive Seminar: Teaching Elementary Pianists. Learn more by clicking here.

My initial short answer to this is: if a parent will practice with the child, then the parent must be involved in the lesson. This will support the child and keep practice focused on goals given by the teacher. My other short answer is: parental support is always needed to schedule the household for regular practice to occur.

I know that children can practice on their own, but I also know that structure is often needed from the parent to ensure complete work. Furthermore, some children feel insecure at the piano alone, while others have never practiced with a parent! In other words, the level of parental participation should be determined by the developmental needs of the child. Some parent-child practice partnerships work well, although the child must be allowed and encouraged to have independent time at the piano to develop agency and intrinsic motivation. Occasionally, I need to encourage parents to embrace the child’s autonomy.

My guidance to parents is based on several simple rules:

Following these guidelines yields at least four days of practice. If assignments are fully completed, and there are four to six days of practice, I find that my students make regular and consistent progress.

The only guideline on practice duration that I maintain is “completion of the assignment.” I estimate my early beginner practice assignments to be 20 minutes in length. As students advance, we discuss length of practice more purposefully, as relates to their goals for study.

My students’ assignments have warmups, new music, review music, and performance repertoire. Warmups include five finger-patterns, chords, progressions, scales, and arpeggios, although often not all at the same time. New/review music will also include quick-learn and for-fun pieces, to result in routine reading and learning of music. Assignments may include etudes and creative skills, like harmonization and lead sheets. Some of my students’ assignments also include supportive activities, such as sight-reading or theory writing pages for review of important concepts. This last category varies widely based upon the needs of the individual.

One of the principles I discuss in my article is developing student ownership. While I give my students typed assignments (printed out or sent electronically), I encourage them to write in their music, and mark all the elements and details that we work on in lessons, in their own handwriting. The assignment sheet will then have weekly goals, written in a concise style. For instance, the student will have formal sections, brackets, and stars written in the music, and the assignment sheet will indicate, “Complete brackets and stars. Play each section 3x slowly.”

This is such an important question, and it is a style of practice that can be overlooked. I work with my students to develop their artistic vision for each section of the piece. I coach them through each section, having them play the section multiple times in a performance flow, seeking to hear better sound each time. This is balanced with slow, purposeful repetition, to secure accurate playing. As the performance nears, I coach them through complete rehearsals, again with a performance mindset of artistic listening.

Interested in learning more from Sara Ernst about teaching elementary pianists? Attend our 2024 Summer Intensive Seminar: Teaching Elementary Pianists. Learn more by clicking here.

We would like to thank Carla Salas-Ruiz for this contribution on writing articles for research publications such as the Journal of Piano Research. Learn more about the Journal of Piano Research by clicking here.

Writing, akin to music, provides a platform for self-expression. It also fosters critical thinking and enables us to articulate diverse perspectives, integrate information, and contribute to the advancement of our discipline. Yet, it’s common for many of us to feel a bit lost, unsure of where to even start. Have you ever found yourself facing a blank page, unsure of what to write or how to transform your project or research study into a compelling and engaging work? I have experienced this scenario several times. However, it wasn’t until I drew parallels between piano practice, lesson planning, and writing that a breakthrough occurred. I am excited to share these connections and encourage you to view academic writing as an art form for which you already possess all the necessary tools. Now is the time to leverage these tools and recognize writing as a creative exploration, where intentional choices and practice yield inspiring outcomes, similar to performing a piece or teaching a lesson.

When practicing any musical piece, it’s crucial to grasp the composer’s expressive ideas and the essence of the composition to shape the interpretation effectively. To do this, we listen to recordings from other performers and study the musical language of the composer throughout their repertoire. Similarly, in writing, the initial step involves gathering exemplary articles from various sources such as journals, magazines, books, and other publications to identify essential elements like structure, language usage, and coherence. Deconstructing these articles, akin to dissecting a musical composition into sections and phrases, facilitates targeted writing practice. Analyzing the author’s intentions behind effective writing serves as a guide in crafting our roadmap. Additionally, extensive reading enriches our understanding and fuels creativity by exposing us to diverse viewpoints and encouraging critical thinking.

Having learned from the insights of fellow writers, now is the ideal time to establish a method. This is similar to creating a practice log, focused solely on the concepts pertinent to your topic. During this phase, your reading should be targeted towards understanding existing discussions relevant to your chosen idea. It is essential to adopt a systematic approach, meticulously extracting key concepts from authors and documenting them methodically. I recommend constructing a table with columns for the source, author’s name, key quotes, year of publication, and page numbers.

After completing your reading journey, it is crucial to define your idea or research question through discussions with peers, similar to seeking feedback on a musical composition. Sharing your ideas with others can be tremendously beneficial, as they serve as a sounding board, potentially providing invaluable clarity to your thoughts. For instance, during my time in graduate school, my focus was on studying motivation. However, given the extensive literature surrounding the concept, it was only upon encountering the theory of Interest Development1 that I could delineate the scope of my idea and purposefully devise a roadmap to satisfy my curiosity. This process was greatly facilitated by continual discussions with colleagues, friends, and professors.

With our ideas taking shape, we transition into methodological design, akin to selecting the appropriate techniques for musical expression. This time is about crafting a research question and defining a plan to answer that question. Establishing a robust research question is imperative, as it serves as a guiding beacon amidst the myriad of available methodologies, including quantitative, qualitative, ethnographic, historical, and/or philosophical approaches. Developing a method involves meticulously outlining the research design, methods, and techniques employed to satisfy your curiosity. It will outline your plans for data collection and analysis. In an academic context, this comprehensive plan encompasses critical decisions about how we chose participants or composers we’ll study, what tools we will use to gather information, how we will analyze that information carefully, and what conclusions we will draw from it. We will also look closely at what the findings mean and how they add to what we already know, the ideas we are working with, and how they can be useful in our field. This thorough analysis involves looking at the results in connection with the questions we asked at the start and the big ideas we are exploring, while also thinking about what they might mean for other important areas. Collaboration could be key in this step. Just as we gather to play beautiful chamber music, collaborate with colleagues that may have additional knowledge in this area, approach them and develop your idea in a multidisciplinary way.

Creating an outline for presenting your writing is essential to maintain clarity and coherence throughout your work. Remember Step 1? This is where your grasp of writing structures and tendencies becomes invaluable in organizing your writing process effectively. Consider these questions to initiate an initial outline:

Ensure you iterate through several drafts and seek feedback from peers and mentors. Crafting a roadmap for written contributions ensures that our ideas are effectively communicated with clarity and impact, much like crafting engaging lesson plans or conducting focused practice sessions. Once you feel confident with your outline, begin writing without self-judgment; allow yourself to simply type! Stick to your outline, but don’t hesitate to make adjustments for better flow if needed. Much like practicing an instrument, this stage represents full engagement in practice: experimenting with specific strategies and refining particular sections.

Just as we can sense when our repertoire is ready for the stage, we also know when our written work is prepared to be shared. Whether through academic journals, book chapters, or magazines, sharing our work enhances communication skills, professional growth, and advances our field. Similar to selecting the ideal venue and format for a recital, deciding where to publish prompts us to find platforms where our contributions align well. After completing our written work and reflecting on “Step 1,” we can determine which journal or magazine best suits our work. There are research-specific journals as well as those catering to practitioners. Understanding the purpose of each publication can assist us in making this decision. In the music field, there are a number of journals, including Piano Magazine and the recently launched Journal of Piano Research. We should consider all options, and after reviewing previous research, we can gauge the expected contributions and target audience.

Recognizing writing as an art form encourages us to engage in a journey of creativity and purposeful expression. Through the process of exploration, refinement, and sharing, we achieve transformative musical and teaching outcomes. Just as musical performance brings compositions to life, as writers we can give vitality and resonance to our ideas, enriching our collective discourse and advancing our field.

Go to journalofpianoresearch.org/ to learn more about this new publication!

MORE ON RESEARCH

We would like to thank Bennyce Hamilton and Rachel Kramer for this insightful article on diversity in the teaching studio. Want to learn more about DEI? Check out our new course, Piano Teaching through the Lens of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. The course is now available for presale purchase. Click here to learn more.

This phrase has been in my vocabulary since I was young enough to understand what it meant. As I have become a performing musician, music educator, and community arts participant, I continue to believe the statement is true. However, as I look at the faces in my studio and consider the studios of my colleagues, I wonder just how “universal” we really are. Who exactly has a seat in our studio? Are there more seats for students of a certain background? For most of us we set a table of convenience, with seats for those in our immediate community who are interested, educated, and able to pay. While it is not our intention to exclude anyone or refuse students, to diversify means that we must do so with intention. Take a moment to consider the faces that populate your studio. What percentages are white, Christian, educated, heterosexual, and middle class? Whether you know the number or have not thought about it— the time for an honest, reflective conversation is long overdue. We need to address diversity deliberately and intentionally within our everyday lives and within our studios. Maya Angelou may be right when she said, “We are more alike than unalike, my friends.” Our understanding and appreciation of diversity remains a crucial step in building and maintaining community. How do we find common ground? How are we being mindful of the differences that exist? How can we change our mindsets to be more inclusive? Our own educational background is heaped in the traditions of Western music. Does this limit our vision or the population of our studios?

Change begins with awareness of ourselves and of our communities. Initiating conversations about diversity may be the first actions we take. Dr. Bennyce Hamilton is the Regional Director of Diversity for Miami University of Ohio. Her work in leading workshops, providing training, and developing “common ground” understanding helps people recognize different points of view and see what it feels like to walk in another’s shoes. Dr. Hamilton’s dissertation presents the idea of becoming a reflexive, culturally-relevant practitioner. Based on her research and current work we will lay the groundwork for all of us to become more intentionally inclusive in our studios. —Rachel Kramer

Beginning the work of inclusion and diversity means that we acknowledge that there are students who are from all faiths/beliefs, races, and socioeconomic levels. This could mean that we need to change our registration forms to say “Guardians,” instead of Mom and Dad. This could mean that we need to change or add to our recital themes or holiday breaks. We must be intentional and purposeful. It is not enough to think or say that you want your business to reflect a diverse population. We must actively seek out those who are not represented. Thinking about our current students: Do they all come from the same neighborhoods and schools? Are they all white? Are they all Christian? Can they all afford music lessons? Do they all have a Mom and Dad? It is only after we have addressed these kinds of questions that we can begin to operate differently. Intention means that we go above and beyond our usual way of conducting business. Intention means that we are deliberate in how we find students, the materials and methods we use, and how we retain students. We must acknowledge that we do not have all of the answers and that we can ask for help.

We hope you enjoyed this excerpt from Bennyce Hamilton and Rachel Kramer’s article “Walk a mile in your neighbor’s shoes: Diversity in the teaching studio.” You can learn more about diversity in the teaching studio by purchasing our newest course, Piano Teaching through the Lens of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. Learn more by clicking here.

MORE ON DIVERSITY, EQUITY, AND INCLUSION

We would like to thank Allison Shinnick Keep for this insightful article on The New School for Music Study’s Postgraduate Teaching Program. Want to learn more about the Postgraduate Teaching Program? Learn more and apply by clicking here.

There are experiences in life that change you slowly over long periods of time, and others that seem to change you in an instant. My experience as a postgraduate fellow at The New School for Music study somehow did both. I experienced daily “lightbulb moments” while observing my mentors and colleagues and felt instantly changed. And yet, I was still surprised at the conclusion of the year: I had transformed. Not only had my teaching transformed, my approach to living life as a musician had transformed. Slowly, day by day, through teaching, observing, reflecting, and engaging, I was growing into a musician and teacher I’d only previously dreamed of becoming.

At the conclusion of my masters program, I found myself burnt out, tired, and aimless, as many young musicians might experience at the end of a degree. Even though my studies had been full of inspiring lessons, collaborative performances, and new teaching experiences, years of academia and striving for the next degree left me with a weary spirit. I knew I still loved and desired a life full of music, but I wasn’t sure how to keep on without burning out even more. Today, I enjoy a life that is filled to the brim with music teaching and performing, and I often forget that I faced those dark feelings nearly eight years ago. My time at The New School reignited my passion and provided me with pedagogical and professional tools that I continue to apply in each new iteration of my career.

Several mentors had encouraged me to apply for the Postgraduate Teaching Fellowship (now the Postgraduate Teaching Program) and I was well aware of the school’s reputation and deep pedagogical history. Even though my future was unclear, I thought “I know teaching piano will always be something I could do, so I might as well go somewhere I know I’ll be taught to do it well.” I can now confidently say that not only did I learn to do it well, but now teaching piano is indeed what I want to be doing. I laugh at my initial reluctance to move across the country, for what unfolded over the course of the next year became the most life-changing experience of my 20s.

I could compile a list of teaching tips, lesson plan guidelines, or favorite teaching repertoire—all of which I certainly gained through my time at the New School and utilize daily in my teaching; however, none of this could encapsulate the magic that’s found inside the walls of the New School. The most impactful aspect of the postgraduate fellowship program was being immersed in a community of loving, encouraging, and inspiring colleagues.

I was especially struck by the integrity and camaraderie of the faculty. Each faculty member is an outstanding teacher in their own right, yet among them you find true humility and a desire to share in the journey of teaching. The faculty at the New School are uniquely collaborative. As a fellow, I wasn’t considered second-tier, but I was immediately embraced as a member of the team. By co-teaching group classes and observing many different colleagues, I gained a coveted look behind the scenes of not just one, but of fifteen master teachers.

With a shared mission of excellence in teaching, the faculty at the New School are one in spirit and always willing to lend a hand or offer advice. As a young teacher, my knowledge of repertoire was limited, but when I had questions about appropriate pieces for my students, fellow faculty members were eager to offer suggestions and tips. I was inspired to see that though teachers set high standards for their students, joy was also found in the small victories in lessons with beginning and advanced students alike.

Prior to my fellowship year, I felt comfortable teaching particular pieces to particular age groups. By the end of my fellowship year, I felt equipped to tackle lessons with students of any age playing any level of repertoire. Through the generosity of my colleagues and their enthusiasm for sharing their own teaching expertise, in a year’s time, I benefited from decades of thoughtful, dedicated teaching practice.

Though life has now taken me away from New Jersey, the New School will always feel like home. It’s where I grew up as a teacher and inside it are many colleagues who have become life-long friends and mentors.

My time at the New School changed me. I truly cannot imagine what my life would look like had I not been a fellow at the New School. Not only did I gain invaluable practical skills and professional connections, I also absorbed the energy and love of teaching that surrounded me every day. I will be forever grateful for the mark that the New School has left on my life.

Learn more about teaching and professional development opportunities at The New School for Music Study by clicking here.

MORE ON THE NEW SCHOOL FOR MUSIC STUDY

We would like to thank Penny Lazarus for this insightful article on inclusive programming. Want to learn more about Penny Lazarus’s work in DEI and her thoughts on inclusive programming? Lazarus is a contributor for our new course, Piano Teaching through the Lens of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. The course is now available for presale purchase. Click here to learn more.

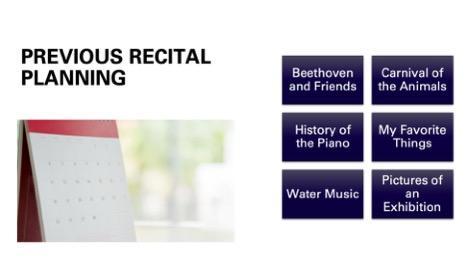

I am an independent music teacher with a 45-student piano studio in Newburyport, MA. Like you, I always wanted our piano recitals to engage and help my students connect expressively with their music beyond just notes on a page. I think you will recognize the recital themes I used before 2015.

In 2016, a new Star Wars movie, The Force Awakens, came out. I created a practice challenge based on that movie, pretending “The First Order” bans all music. Our students had to preserve the world’s music until “The Resistance” could find Jedi Luke Skywalker and restore the universe. For every piece learned, my students added a glow-in-the-dark star to the ceiling of my studio. They tended to group their stars into distinct separate “neighborhoods” representing individual symbols of achievement. Dismayed by these walled-off individual neighborhoods, the following week, I laid out a map of our solar system. From then on, students placed their stars to match the constellations of our universal night sky. We celebrated music making together in an informal recital under our glowing stars and a feeling of community in the studio was born.

I couldn’t shake the feeling that entire countries had cultural bans in place that severely limited the study of music, art, and literature. The following year, 2017, I decided to explore Eastern European music, a topic I knew little about except the work of Béla Bartók. It takes some trust in the universe “to go where one hasn’t been before” as a piano teacher. But it is invigorating to explore a new topic. I mentioned this to an acquaintance and learned her husband was working with the Peace Corp in Albania, a country in the Balkans. He had befriended a wonderful Albanian composer Alban Dhamo. I learned Albania only recently emerged from five decades of an oppressive dictatorship that banned all cultural practices. Alban and his wife Erinda Agolli, an opera singer, helped launch the Lincoln Center for the Arts, named after Abraham Lincoln, in the capital city Tirana, to restore piano lessons for local children. The school had only a few electric keyboards and little music. We created a cultural exchange: Alban wrote twenty pieces for our studio, based on Bartók’s Albums for Children, using Albanian folk melodies. We raised money to send over a hundred leveled-music books. Alban’s Balkan rhythms were tricky, but I witnessed new energy from my students who practiced harder than ever, because they had a personal stake and a responsibility for engaging with a living composer in another part of the world. When they played Alban’s pieces during a Facetime recital, the composer was brought to tears.

We hope you enjoyed this excerpt from Penny Lazarus’s article “Cultivating Brave Spaces in the Piano Studio Using DEI Repertoire and Practices.” You can read more by purchasing our newest course, Piano Teaching through the Lens of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. Learn more by clicking here.

MORE ON DIVERSITY, EQUITY, AND INCLUSION

Join Leah Claiborne with Craig Sale as she discusses equity and belonging in the world of classical music.

Podcast: Play in new window