We would like to thank Tsz Hin Lam for this article on Dan Zhaoyi. Interested in learning more about Dan Zhaoyi? Attend this session at The Piano Conference: NCKP 2025 online conference on Sunday, June 8, 4:00-4:25pm EDT. Learn more and register for the online and in-person conference here.

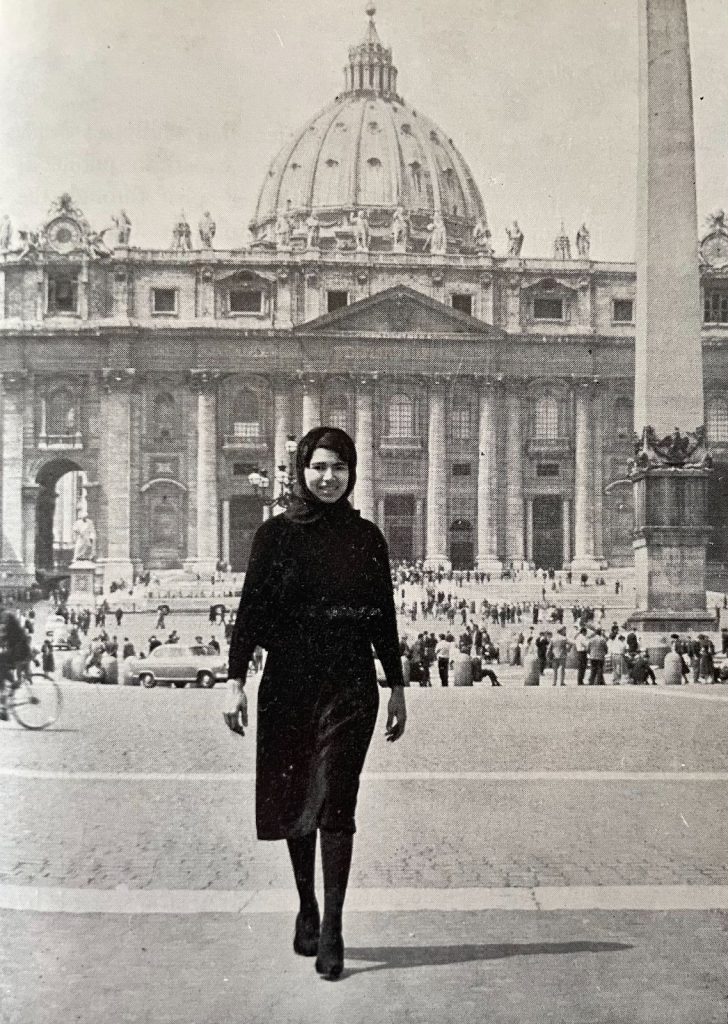

1. Dan, born 1940, was a student of renowned Chinese pianist Zhou Guangren.

Zhou Guangren, who was born in Hannover, Germany, in 1928 to Chinese parents pursuing their studies abroad. In 1933, she returned to China with her family and settled in Shanghai. Zhou was a Chinese pianist and pedagogue who served as a tenured professor and former head of the Piano Department at the Central Conservatory of Music in China. She was the first Chinese pianist to win an award at an international piano competition and was hailed as the “Soul of Chinese Piano Education.”1

2. Record-Breaking Students!

Over 26 of Dan’s students have collectively won 70 international piano competition awards, including 26 first-place prizes.2 This achievement underscores his exceptional impact on the global piano scene. He has mentored some of the most celebrated pianists, including Yundi Li, who won the prestigious International Chopin Piano Competition in 2000, and Zhang Haochen, the first Chinese winner of the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition in 2009.

3. Prolific Author:

In addition to his teaching legacy, Dan has authored pivotal works on piano pedagogy, such as Piano Teaching and Guidance for Children, New Paths Piano Fundamental Course, and Dan Zhaoyi’s Piano Teaching Essays. These publications have become indispensable resources for piano students and educators, not only in China but across the globe.

4. Chinese Characteristics in Piano Teaching Approaches

Dan’s approach to piano education emphasizes not only technical proficiency but also a deep appreciation for music, which may include elements and pieces that resonate with Chinese musical traditions and values. This makes his materials unique and well-received in China. Dan’s teaching materials, such as his New Paths Piano Fundamental Course, are known for incorporating elements that reflect Chinese characteristics. This series is described as having “scientific, systematic, national, and interesting features,”3 which suggests a thoughtful integration of Chinese national music into the curriculum.

5. “Godfather” of Piano Education in China

Dan stands as one of China’s most influential piano pedagogues of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. With a teaching career spanning over six decades, he has earned the revered title of “Godfather of Piano Education”4 due to his significant contributions to nurturing world-class Chinese pianists.

Notes

- Piano League, “Zhou Guangren, “Soul of Chinese Piano Education”, Dies at 94,” Piano League (Blog), March 7, 2022, https://thepianoleague.com/news/guangren-zhou-soul-of-chinese-piano-education-dies-at-94/.

- “Dan Zhaoyi – Professor Emerita, Shenzhen Arts School,” Bay PianoFest, Artcial Music Foundation, accessed May 24, 2025, https://baypianofest.org/dan-zhaoyi.

- “Artistic Director,” China Shenzhen International Piano Concerto Competition, published 2018, accessed May 24, 2025, https://www.csipcc.com.cn/about-us/artistic-director/.

- Qian Zhang, “Dan Zhaoyi: ‘Godfather’ of Piano Education,” Shenzhen Daily, (2018), https://web.archive.org/web/20181024171055/http:/www.szdaily.com/content/2018-10/19/content_21155125.htm.

Resources

“Artistic Director.” China Shenzhen International Piano Concerto Competition. Published 2018. Accessed May 24, 2025. https://www.csipcc.com.cn/about-us/artistic-director/.

“Dan Zhaoyi – Professor Emerita, Shenzhen Arts School.” Bay PianoFest. Artcial Music Foundation. Accessed May 24, 2025. https://baypianofest.org/dan-zhaoyi.

Piano League. “Zhou Guangren, “Soul of Chinese Piano Education”, Dies at 94.” Piano League (Blog). March 7, 2022. https://thepianoleague.com/news/guangren-zhou-soul-of-chinese-piano-education-dies-at-94/.

Zhang, Qian. “Dan Zhaoyi: ‘Godfather’ of Piano Education.” Shenzhen Daily, (2018). https://web.archive.org/web/20181024171055/http:/www.szdaily.com/content/2018-10/19/content_21155125.htm.

MORE ON THE PIANO CONFERENCE: NCKP 2025

- THE PIANO CONFERENCE: NCKP 2025

- PIANO MAGAZINE: Some reflections on the 2005 National Conference on Keyboard Pedagogy (NCKP) by Elvina Truman Pearce

- WEBINAR: NCKP 2023 Committee Webinar: How to Practice Jazz and Improvisation with Jeremy Siskind

- WEBINAR: Teaching Demonstration (NCKP Rebroadcast) with Marvin Blickenstaff

- DISCOVERY PAGE: The Benefits of NCKP: The Piano Conference and Why You Should Attend by Marvin Blickenstaff

- DISCOVERY PAGE: What to Expect at The Piano Conference: NCKP 2025: From the Inclusive Teaching Track and Keyboard Lab Presentations by Derek Kealii Polischuk and Sara Ernst

- DISCOVERY PAGE: What to Expect at The Piano Conference: NCKP 2025: From the Technology and New Professionals Tracks by Stella Sick and Allison Shinnick Keep

- DISCOVERY PAGE: What to Expect at The Piano Conference: NCKP 2025: From the International Track by Luis Sanchez

- DISCOVERY PAGE: What to Expect at The Piano Conference: NCKP 2025: From the Collaborative Performance and Research Committee Chairs by Sara Ernst, Alexandra Nguyen, and Alejandro Cremaschi

- DISCOVERY PAGE: What to Expect at The Piano Conference: NCKP 2025: From the Performance Practice, Teaching Adults, and Business & Entrepreneurship Committee Chairs by Sara Ernst, Andrew Cooperstock, Jackie Edwards-Henry, and Andy Villemez

- DISCOVERY PAGE: What to Expect at The Piano Conference: NCKP 2025: From the Creative Music Making, Independent Studio Teachers, and Young Musicians Committee Chairs by Sara Ernst, Jason Sifford, Janet Tschida, and Jeremy Siskind

- DISCOVERY PAGE: What’s New at The Piano Conference: NCKP 2025 by Sara Ernst, Michaela Boros, and Megan Hall

- WEBINAR: NCKP 2023 Committee Webinar: Facing the Future with Jason Sifford