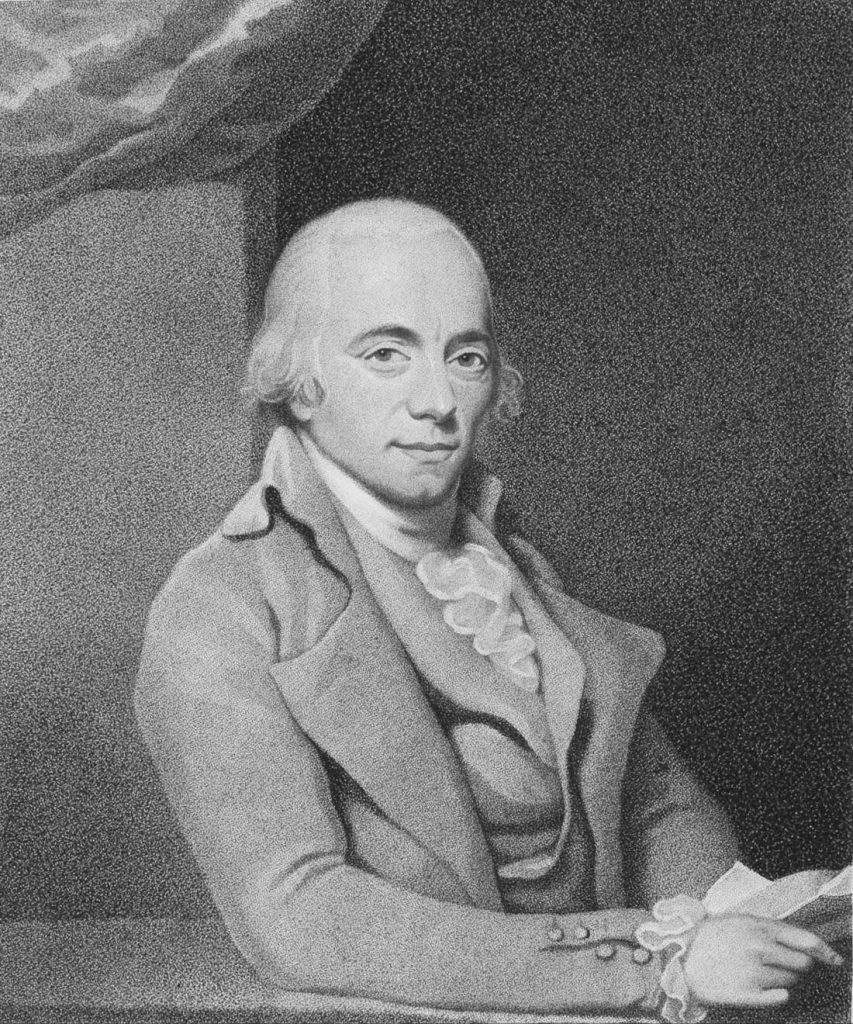

THIS WEEK IN PIANO HISTORY, we remember composer and organist Charles-Louis Hanon, who died on March 19, 1900 in Boulogne-sur-Mer, France. Author of the infamous collection The Virtuoso Pianist, Hanon is little known besides this work.

Hanon was born in Renescure, a village in northern France. He learned to play organ and later moved to Boulogne-sur-Mer, a coastal city in northern France approximately sixty kilometers away, where he would spend the rest of his life. Hanon worked at the Église Saint-Joseph as a church organist, but resigned his position in 1853; there is speculation as to the exact reasons for his resignation, but some have speculated that he was forced to resign.1 Despite this, Hanon was a lifelong and devout Catholic. Hanon served in the “Les Frères Ignoran tins,” a monastic order that emphasized education for poor children.2 Although primarily focused on his religious callings, Hanon also composed and published a number of keyboard works.

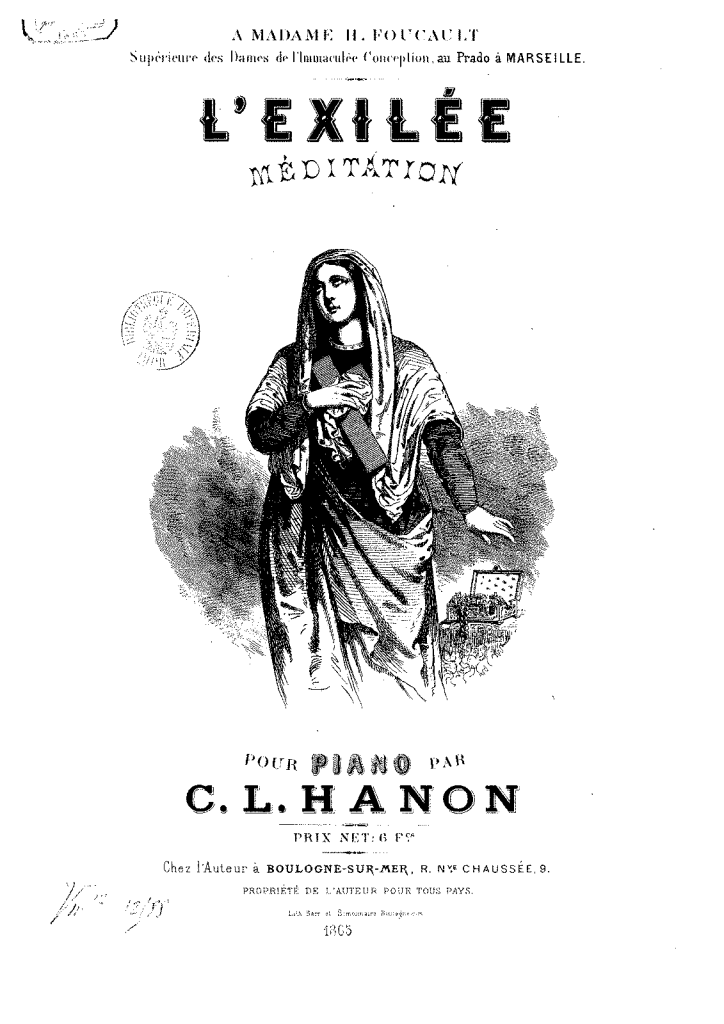

Hanon’s output includes several works with programmatic titles as well as many works specifically designed for pedagogical purposes. His work, Les montagnes de la Savoie, written for solo piano, is a fantasy in which limited thematic material is repeated with slight alterations to the dynamic level and register. The piece includes a significant repeated note passage as well as chromatic scales, arpeggios, and broken chords. Another work, Souvenirs de Bretagne or Fantaisie brillante sur des airs bretons (Brilliant Fantasy on Breton Tunes), includes melodies from the Brittany region of France. Some of the melodies are given virtuosic accompaniments, while others have more traditional accompanimental patterns. In his L’exilée (The Exile), Hanon presents a work that contains a significant amount of music for left hand alone, complete with filigree, variation, and arpeggiation.

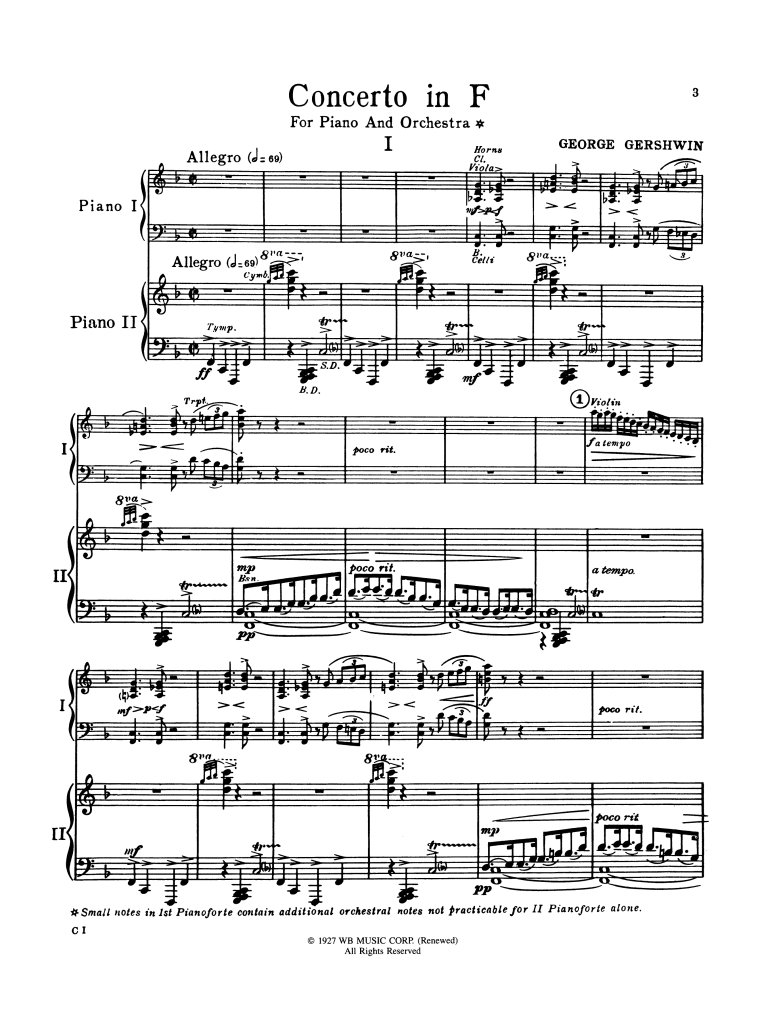

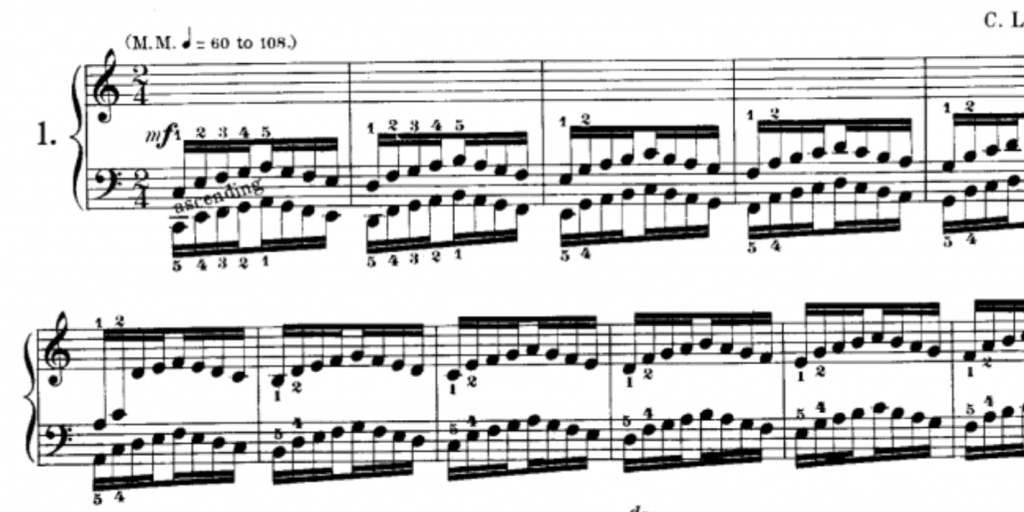

His most famous work, The Virtuoso Pianist was first published in 1874 and is known worldwide for its use amongst pianists of all levels, including virtuosos such as Sergei Rachmaninoff and Josef Lhévinne.3 Despite this, the work is clearly influenced by other composers, such as Aloys Schmitt who wrote an identical exercise to Hanon’s first exercise more than fifty years prior.4 The Virtuoso Pianist contains five-finger exercises in various patterns, all the scales and arpeggios, as well as more challenging exercises in octaves and repeated notes. Hanon’s work was so popular in the twentieth century that Dmitri Shostakovich even included varied excerpts of the patterns in his Piano Concerto No. 2 in F Major, Op. 102. Today, many pianists continue to study the work significantly, transposing the exercises into various keys.

Interested to learn more about using piano etudes in creative ways? Read this article by Scott McBride Smith:

OTHER RESOURCES YOU MIGHT ENJOY:

- DISCOVERY POST: This Week in Piano History: The King of Etudes by Curtis Pavey

- MAGAZINE ARTICLE: What is the role of “etudes” in a pianist’s development? Which ones do you use and when? By Nancy Bachus

- MAGAZINE Article: Healthy Technique for Beginning Students by Rebecca Grooms Johnson and Marvin Blickenstaff

- WEBINAR ARCHIVE: Techniques for Beginning Pianists with Penelope Roskell

- REPERTOIRE VIDEO SERIES: Etudes with Marvin Blickenstaff

- Use our search feature to discover more!

Sources

- Andrew Adams and Bradley Martin, “The Man Behind the Virtuoso Pianist: Charles-Louis Hanon’s Life and Work,” The American Music Teacher 58, no. 6 (Jun, 2009): 18-21, uc.idm.oclc.org/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Ftrade-journals%2Fman-behind-virtuoso-pianist-charles-louis-hanons%2Fdocview%2F217493040%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D2909.

- Ibid.

- “Charles-Louis Hanon,” In Wikipedia, Accessed February 27, 2023, wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles-Louis_Hanon

- Andrew Adams and Bradley Martin, “The Man Behind the Virtuoso Pianist: Charles-Louis Hanon’s Life and Work,” The American Music Teacher 58, no. 6 (Jun, 2009): 18-21, uc.idm.oclc.org/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Ftrade-journals%2Fman-behind-virtuoso-pianist-charles-louis-hanons%2Fdocview%2F217493040%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D2909.

Adams, Andrew and Bradley Martin. “The Man Behind the Virtuoso Pianist: Charles-Louis Hanon’s Life and Works.” The American Music Teacher 58, no. 6 (Jun, 2009): 18-21. uc.idm.oclc.org/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Ftrade-journals%2Fman-behind-virtuoso-pianist-charles-louis-hanons%2Fdocview%2F217493040%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D2909.

“Charles-Louis Hanon.” In Wikipedia. Accessed February 27, 2023. wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles-Louis_Hanon