We encourage you to watch Holly Kessis’ archived webinar here: “Piano Inspires… Innovation in Practice“ with Igor Lipinski, Brianna Matzke, Joy Morin, Melody Ng, Jason Sifford, and Jennifer Snow. This webinar is a celebration of innovation in organizations, teaching practices, and teacher education.

1. Less is more.

It’s easy to get overwhelmed with ideas, so start by picking one era or genre of piano music to focus on and stick to it. What style of music do your students perform especially well? Have you had success in your studio with music by Russian composers, miniatures from the Romantic period, popular tunes, or movie soundtracks? You could even concentrate on repertoire related to one specific word (some examples: “autumn” or “celebration” or “colors”). Make sure that whatever you pick still has enough variety to encompass a whole recital.

2. Survey your students.

What inspires your students in their music-making? Maybe some of them are learning about music from the 1960s at school and ask about playing by The Beatles or Janis Joplin. Perhaps you have a few students struggling to stay motivated but light up when you mention a tune from their favorite video game. I had one child who gravitated towards quirky Kabalevsky pieces and only wanted to play those at recitals! Following your students’ interests will keep performances exciting and can lead to new possibilities for those students for whom the new genre or composer is new.

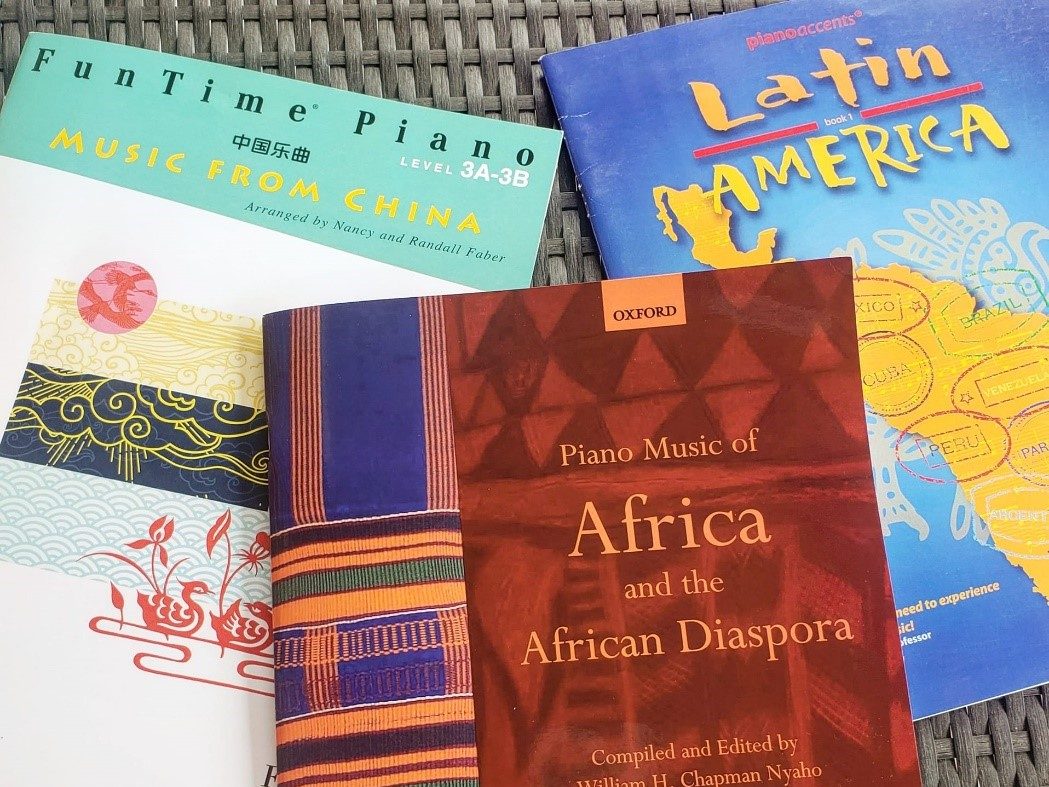

3. Go outside of your comfort zone.

Is there an artist or music style that you would love to make more time to discover? In the beginning of 2021, I started searching for music outside of the typical western styles I was used to and eventually created a “Music from Around the World” theme including beginner and intermediate songs from Africa, Asia, and South America. More preparation was involved, but this certainly broadened my horizons as a teacher trained in the classical tradition and exposed my students to appealing tunes they wouldn’t be exposed to otherwise.

4. Think “interdisciplinary”.

Solo piano study doesn’t exist in a vacuum.Are there other art forms that could be combined with your students’ musical performances to add depth? Maybe you have some budding artists in your studio who could create artwork to go along with their pieces. Videos displaying landscapes or abstract animations could add to the mood of your students’ performances. Even collaborating with children taking dance classes or playing different instruments besides piano can pique the interest of the audience.

5. Pick a new place!

Who says your recital has to be at a usual performance space? Reach out to small businesses in your community like a local coffee shop to see if they have the time and space for a small concert. Perhaps a neighboring retirement home or arts council center has an hour set aside in their schedule every week for outside performances. It’s important to get your students used to playing in new and different environments, and the commercial exposure for your studio is a plus.

Other resources you might enjoy

- DISCOVERY POST: Teaching Contemporary Music: Q&A with Brendan Jacklin, by Brendan Jacklin

- PIANO MAGAZINE ARTICLE: Positive Recitals for Young Students: Setting the Stage for Success, by Diane Briscoe

- PIANO MAGAZINE ARTICLE: The Project Recital: Repertoire Awareness in the Music Studio, by Kristin J. Taylor

- WEBINAR ARCHIVE: Creative Solutions for Online Studio Recitals, featuring Sara Ernst, Rebecca Pennington, Anna Beth Rucker, and Leila Viss

- REPERTOIRE VIDEO SERIES: From the Artist Bench — Explore advanced repertoire

- REPERTOIRE VIDEO SERIES: Inspiring Artistry — Explore intermediate repertoire

- Use our search feature to discover more!