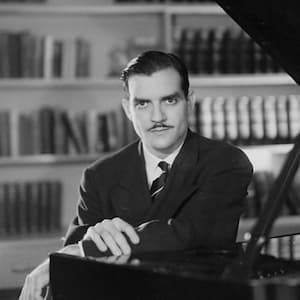

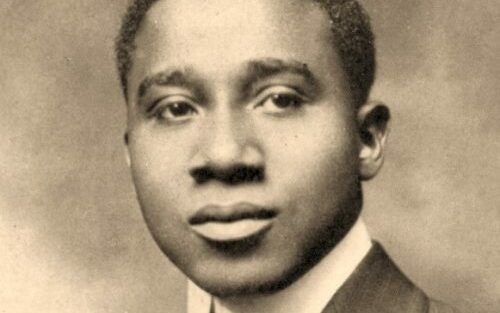

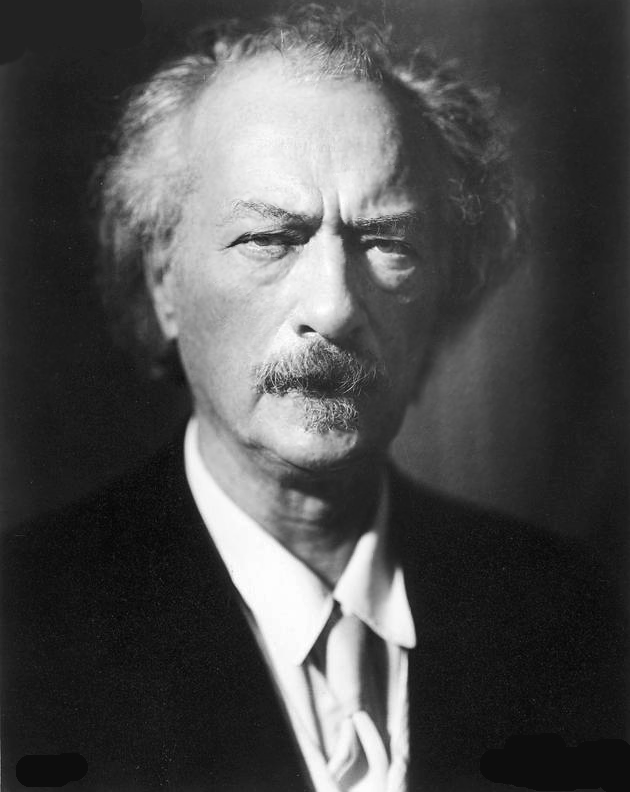

THIS WEEK IN PIANO HISTORY, we reflect upon the resignation of Ignacy Jan Paderewski as Prime Minister of Poland on November 27,1919.1 An important pianist, composer, and statesman, Paderewski’s influence and legacy in Polish culture and early twentieth-century politics is undeniable.

Paderewski was born in Kursk, Podolia, which is now part of Ukraine. He had a complicated childhood as his mother passed away after his birth and his father was arrested due to his suspected involvement in a political uprising. Despite the challenges his family faced, Paderewski studied piano as a child and showed great potential. His talent helped him find opportunities to study in the Warsaw Conservatory and to establish himself as a pianist and composer. His challenges did not stop there—after marrying his first wife, Antonina, they produced a son named Alfred. Both Antonina and Alfred died young, causing great distress to Paderewski. He also struggled professionally, barely making ends meet through his musical career.

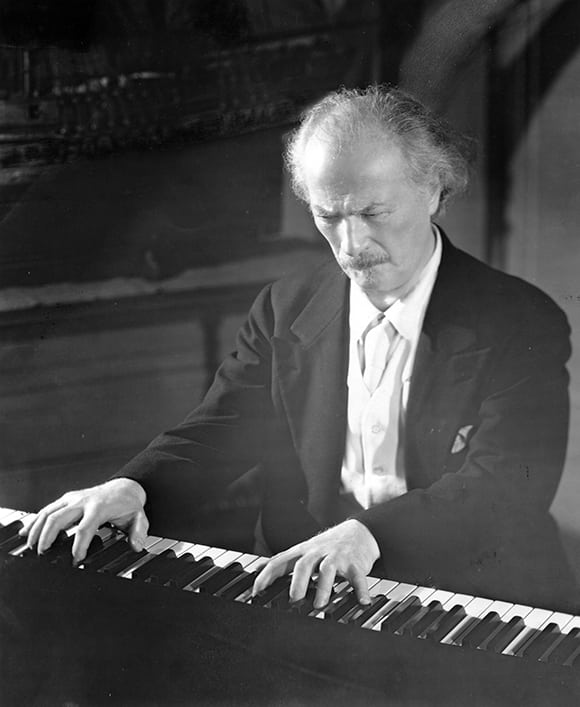

After traveling to Berlin, Paderewski met a number of important composers who encouraged his career.2 This experience led him to the opportunity to study with Theodor Leschetizky, a highly respected piano teacher of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. From here, Paderewski was able to establish himself as a performer, touring the United States and Europe. One of Paderewski’s most popular pieces was his Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 17, written in 1888. The piece, dedicated to Leschetizky, is infrequently performed today, but contains a variety of technically challenging passages in a typical Romantic style.

As a performer, Paderewski was well respected as a masterful and spontaneous performer. He frequently personalized his interpretations of other composers’ works noting: “It is not a question of what is written, it is a question of musical effect.”3 Despite the public’s admiration, Paderewski greatly struggled with nervousness throughout his concert career, frequently taking extended breaks in order to recover from the strenuous concert schedule he maintained.

Paderewski’s role in Polish politics is complicated. Throughout his life, Paderewski often championed causes for Polish independence. Poland was frequently partitioned by neighboring empires in Austria, Germany, and Russia prior to gaining independence in the twentieth century. During the First World War, Paderewski made Polish causes a focal point of his public activities. Woodrow Wilson, then President of the United States, requested his help in securing votes for his presidency in return for supporting Polish independence.4

After the war ended, Paderewski was tapped by Józef Piłsudski, then the Polish Chief of State, to become the Prime Minister of Poland. He was ousted after less than a year in the position due partially to his underdeveloped leadership skills. Although Paderewski represented Poland again in 1920 in political office, he again resigned and returned to pursue a career in music before dying on June 29, 1941 in New York City.

Looking back on Paderewski’s life and career, it is clear that Paderewski frequently overcame obstacles that challenged him personally and professionally. His legacy as a pianist and statesman shows the results of his tireless efforts to find purpose and success in his difficult life.

Sources

- Some sources give conflicting dates (December) for Paderewski’s resignation as Prime Minister of Poland.

- Jim Samson, “Paderewski, Ignacy Jan,” Grove Music Online, 2001, accessed 15 Nov. 2022, www-oxfordmusiconline-com.uc.idm.oclc.org/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000020672.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.