We would like to thank Ali Snow for this insightful article on managing performance anxiety and motivation. Want to learn more about motivation? Join us on Wednesday, January 24, 2024 at 11am ET for “Determinants of Motivation in World-Class Musicians and Olympic Athletes: Exploring the Front and the Back Side of the Medallion,” a webinar that highlights connections between sports and music research. Learn more and register by clicking here.

Mastering the inner game: Three “mind coaches” on managing performance anxiety

“Don’t be nervous! You’ll do fine!” “Take a few deep breaths and it’ll all be OK.” “Here, eat this banana. It’ll help your nerves.” “Just picture the audience in their underwear!” “You should put yourself in a lot of pressure-filled situations and soon you’ll just get used to it.”

Sound familiar? These are just a few of the most common answers musicians hear when asking how to overcome performance anxiety. Although well intentioned, each statement is either false folklore or a fad that has gone in and out of style. So why are students seeking advice in the first place? Perhaps it is because one of the biggest challenges many music teachers face is how to adequately prepare their students for the mental side of performance. In his classic book The Inner Game of Tennis, author W. Timothy Gallwey wrote, “Every game is composed of two parts, an outer game and an inner game.”1 If this is true, then how can teachers effectively teach the inner game, a game that often seems so abstract? This question will be explored through tips from three leading minds in this arena: performance coaches Jon Skidmore and Kjell Fajèus, and sports psychologist Richard Gordin.

Physiological responses and the brain

According to Jon Skidmore, a performance coach and adjunct professor at Brigham Young University, the first major obstacle in approaching the inner game is rooted in the very definition of a “performance.” Rather than labeling it as an event, a performance should be shifted into the context of a process. “If you’re a professional and you’re throwing a gig, that’s an event. There are certain expectations,” says Skidmore. “But if you’re a student learning, you’ve got to look at this as an experience—whether it’s a performance or recital or audition. [This is] part of the process of becoming the musician you want to be.”

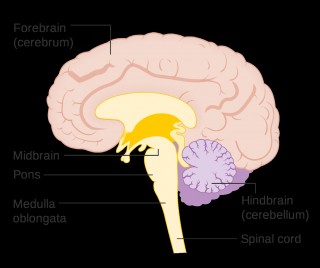

Consider how an event is processed in the mind: A portion of the brain called the midbrain constantly scans every experience for danger. It functions as a survival center (see Figure 1). “Once something has been programmed into the midbrain, there’s an automatic response,” says Skidmore. “It is often referred to as the ‘fight, flight, or freeze’ response. Now that works great for a rattlesnake, but it can be devastating in an audition.”

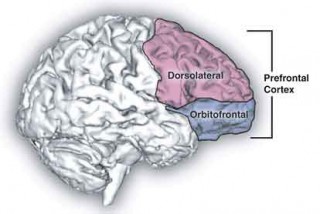

What Skidmore suggests is to shift the focus out of the midbrain and into another area, the prefrontal cortex (see Figure 2). This highly-developed part of the brain assigns meaning and allows for reasoning. By making this change, students can be in control by designing their mindset, rather than reacting by default.

Illustration by Wikimedia Commons

We hope you enjoyed this excerpt from Ali Snow’s article “Perspectives: Managing performance anxiety.” You can read more by clicking here.

MORE ON PERFORMANCE ANXIETY AND WELLNESS

- MAGAZINE ARTICLE: Mindfulness in the Piano Lesson: Where do We Start? by Fernanda Nieto

- DISCOVERY PAGE: A Quick Look at Wellness: What Pianists Should Know by Laura Amoriello, Jessica Johnson, Carina Joly, Brenda Wristen, Vanessa Cornett, Lesley McAllister, Paola Savvidou, Linda Cockey

- MAGAZINE ARTICLE: My Journey to Healthy Musicianship: Practical Ideas for Exploration and Self-Reflection in the Piano Studio by Carla Salas-Ruiz

- MICROCOURSE: Performance Anxiety Management: How to Prepare for Your Best Performance

- MAGAZINE ARTICLE: How do you deal with “stage fright” or performance anxiety? by Nancy Bachus, Gail Berenson, and Julie Jaffee Nagel