Quer saber mais sobre dedilhado? Inscreva-se no nosso webinar internacional gratuito, “ A dedilhação como elemento de expressividade na performance pianística” apresentado por Luis Pipa no dia 4 de novembro. Saiba mais e inscreva-se aqui: https://pianoinspires.com/webinar/11-04-23-webinar/.

The following contribution from Bruce Berr appeared in an article edited by Richard Chronister titled “How Do You Teach Students to Plan Fingering” from Keyboard Companion, Spring 1995, Vol. 6, No. 1. The entire article is found here: https://pianoinspires.com/article/how-do-you-teach-students-to-plan-fingering/.

The teacher must consider the skills that the student has already mastered…

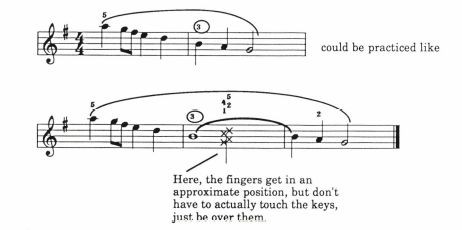

The most important fingering idea that beginners must learn is that five fingers fit conveniently over five adjacent keys. This basic “prime directive” of fingering provides the rule while students begin to experience elaborations on this principle. A crossover is usually the first kind of shift that might make the student think that the five-finger idea is no longer operative. I teach students to feel a crossover not as a finger reaching for a key but rather as a smooth rollover from one five-finger position to a different one; it is important that the entire hand move into place as the crossover happens. An effective way to guarantee this is to have the student insert a practice pause while holding the crossover note. This allows the hand to comfortably feel a new five-finger position before playing is resumed:

What is temporarily sacrificed by this rhythmic interruption is more than compensated for by a fluid, relaxed motion. When students first do crossovers, I’m pleased when the music has the finger cue written in for the crossover note and for the note that immediately follows it so that the idea of having moved into a new five-finger position is communicated. I also hope that there are no more finger numbers written in if all of the notes in that phrase already fall comfortably under the fingers because those would be unnecessary and therefore detrimental. Only essential finger cues should be in the student’s music; if extraneous ones are allowed to remain, students eventually learn to ignore all fingerings, even the good ones.

Which fingerings should remain in the score becomes more complex at the mid- and late-elementary levels. As teachers of this music, we must constantly “read between the lines” to interpret what is meant and what is not meant by a given fingering. I frequently struggle with this problem as a composer and arranger of educational piano music, due to an unavoidable fact: all fingering cues imply a certain approach to technique and teaching. Therefore, an educational author has at least three possible choices: 1. Indicate fingerings that represent the easiest possible physical approach; or 2. Indicate fingerings that represent the easiest possible conceptual approach; or 3. Indicate no fingerings at all.

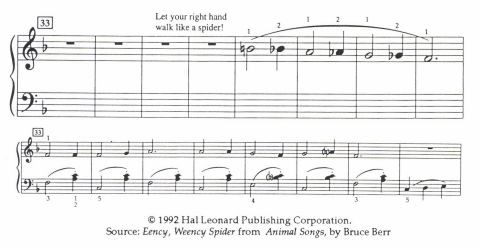

When (1) and (2) are the same fingering there is no problem, but frequently they are not the same, so a choice must be made. Any fingering that a composer or editor indicates tends to unwittingly favor one approach over another. For example, in this elementary excerpt from Eency, Weency Spider, the student gets to play a fun, short chromatic fragment in a piece that is predominantly in five-finger positions elsewhere. The printed fingerings are the easiest from a conceptual standpoint, because the keys are next to each other and so are the fingers that play them; this is an important idea to reinforce at this level. The given fingering also encourages the student’s hand to, well, “walk like a spider”!

I also considered the following fingering: 1-3-1-3-1-3-1. This fingering is better from a physical standpoint because it invites greater participation of the entire hand and forearm in rotating, and thus it produces a freer and more balanced gesture. However, this fingering contradicts our “prime directive” by using non-adjacent fingers on keys that are as adjacent to each other as can be; thus, it may set back our work with students who have needed reminding about fingering in five-finger positions. I could have also indicated no fingering at all in this passage. This would make it convenient for each teacher to use his or her own fingering without having to leave behind a trail of blackened splotches on the page. If a child were learning this piece without the benefit and guidance of a teacher, however, an absence of fingering hints might breed all kinds of indecent fingerings not fit to print here!

Thus, for a teacher to make best use of whatever fingerings do appear printed in educational music, the teacher must interpret each fingering to ascertain its benefits and disadvantages, and must consider the skills that the student has already mastered or not mastered. Only then can an assessment be made whether a particular student will benefit from the given fingering, or whether a different one would be more suitable. In the above passage, if a student has been playing comfortably in five-finger positions, replacing the 2s with 3s would allow that student to experience a new fingering principle. For students who still look at their hands while playing in five-finger positions, however, this indicates a lack of fluency in reading and playing within five-finger positions; thus, the original, safer-feeling fingering would be better.

MORE ON PIANO FINGERING

- MAGAZINE ARTICLE: How Do You Teach Students to Plan Fingering? by Richard Chronister, Bruce Berr, Martha Braden, Suzanne Torkelson, and Elizabeth Caluda

- MAGAZINE ARTICLE: Spring 2022: Discover: Book Reviews: The Performing Pianist’s Guide to Fingering by Daniel Glover

- MAGAZINE ARTICLE: Finding Fingerings that Fit by Brenda Wristen

- MAGAZINE ARTICLE: 2015 Clavier Companion Collegiate Writing Contest Runner-Up: Survival of the fittest: A reevaluation of traditional scale and arpeggio fingerings by Michael Clark