THIS WEEK IN PIANO HISTORY, we celebrate the premiere of Charles Ives’ Concord Sonata, which American pianist John Kirkpatrick premiered on January 20, 1939. The sonata, Ives’ second piano sonata, lasts over forty-five minutes and is noted for its extremely dense writing and complicated use of leitmotifs.

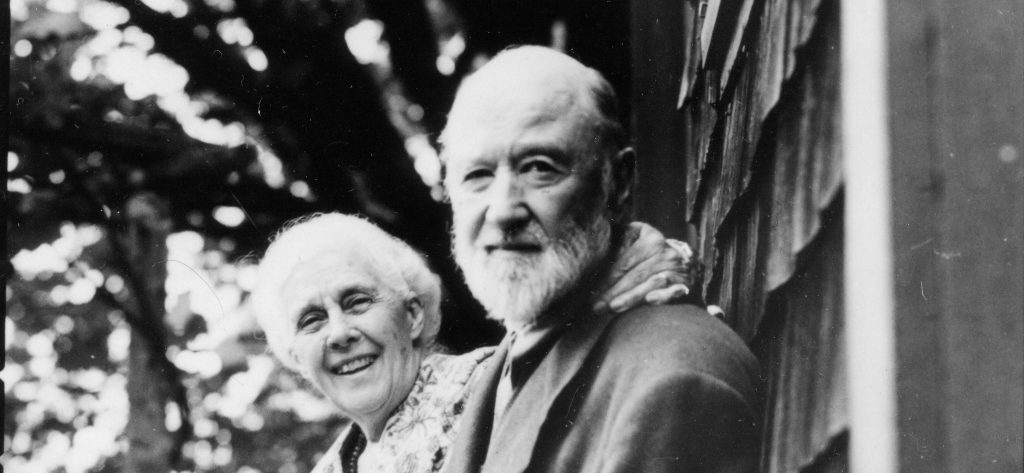

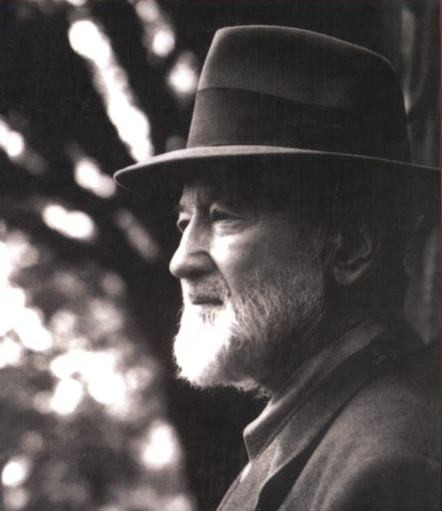

Ives was an American musical pioneer who was known for his colorful and fascinating musical palette. Ives’ father, George E. Ives was one of his primary teachers and held a number of musical positions in Connecticut where he conducted multiple ensembles. Charles Ives grew up studying with his father and played several instruments including piano, organ, and drums, which he performed in his father’s band. Ives experimented throughout his life with a variety of sound worlds including microtonality and polytonality.

Ives’ Concord Sonata was published as his second and final piano sonata in 1920, but Ives revised it a number of times. In the sonata, Ives reflects on writings from poets in the New England area. Each of the different movements of the sonata is titled after a famous American writer including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Bronson Alcott, and Louisa May Alcott. Although written for solo piano, the sonata includes noted solos for flute, viola, and a block of wood, which is used to play clusters in the Hawthorne movement. The sonata is dense, featuring leitmotifs from Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, several hymns, and other excerpts of works by composers such as Debussy and Wagner.1

In addition to the sonata, Ives wrote an essay titled Essays Before a Sonata, in which he described his new musical aesthetics. In writing this document, he joined a number of other twentieth-century composers such as Olivier Messiaen who wrote about their musical methods.

Although the sonata initially received mixed reactions, it was later praised by American author Henry Bellamann who described it as “elevating and greatly beautiful.”2 A number of pianists have recorded the work in recent years including Stephen Drury, Marc-André Hamelin, Gilbert Kalish, and Pierre-Laurent Aimard.

Interested to hear a recording of Ives’ Concord Sonata? Listen to this recording of Stephen Drury performing the work in Jordan Hall at New England Conservatory in Boston, MA.

Sources

- James B Sinclair, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Music of Charles Ives, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 227.

- J. Peter Burkholder, James B. Sinclair, and Gayle Sherwood Magee, “Ives, Charles,” Grove Music Online (16 Oct. 2013; Accessed 15 Dec. 2022), www-oxfordmusiconline-com.uc.idm.oclc.org/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-1002252967.

Burkholder, J. Peter, James B. Sinclair, and Gayle Sherwood Magee. “Ives, Charles.” Grove Music Online. 16 Oct. 2013; Accessed 15 Dec. 2022. www-oxfordmusiconline-com.uc.idm.oclc.org/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-1002252967.

Sinclair, James B. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Music of Charles Ives. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999.