THIS WEEK IN PIANO HISTORY we celebrate the premiere of Gershwin’s Piano Concerto in F on December 3, 1925 in New York’s Carnegie Hall with Gershwin at the piano. After the success of his Rhapsody in Blue, Gershwin set out to prove to the classical musical world that he could handle a traditional classical form and the challenge of orchestration.

Commissioned by Walter Damrosch and the New York Symphony Society, Gershwin composed the concerto over several months in the summer of 1925. Gershwin completed much of the composition in a practice shack at the Chautauqua Institution, an educational center in Chautauqua, New York. Unlike the Rhapsody in Blue, which was orchestrated by Ferde Grofé, Gershwin wanted to orchestrate his concerto and spent several months studying orchestration and getting feedback from other talented arrangers and orchestrators. He finished the orchestration in November 1925, just in time for the premiere in December of the same year. Gershwin remarked about the concerto: “many persons had thought that the Rhapsody was only a happy accident… I went out to show them that there was plenty more where that came from.”1 The premiere of the piece did not see the same success as the Rhapsody in Blue, though it was positively critiqued by the likes of Rachmaninoff.

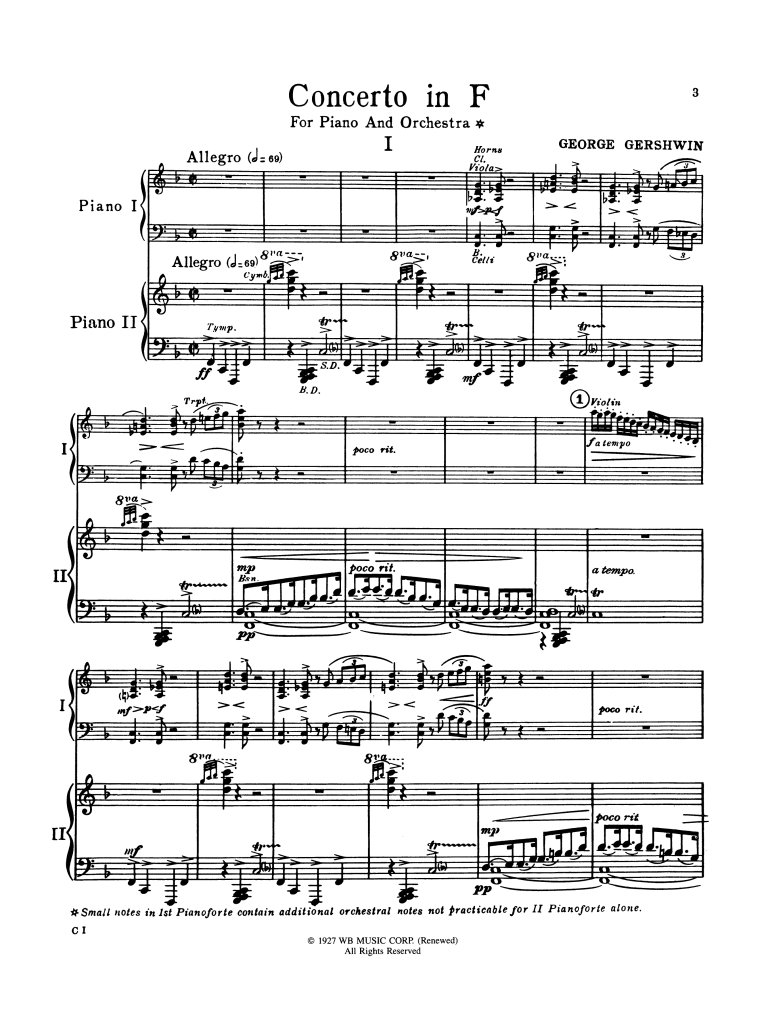

The concerto is a three-movement work in a traditional fast-slow-fast scheme. Gershwin uses elements of jazz such as the blues scale, call-and-response figures, syncopation, and more to evoke sounds similar to the musical style of the Rhapsody in Blue. The first movement, marked “Allegro,” is in sonata form and begins with a short orchestral introduction before the piano enters with a bluesy solo spotlighting the pianist. Two themes from the orchestral and piano introductions stand out: a dotted figure introduced first in the bassoon part, and this jazzy, nostalgic theme presented in the piano.2 The first movement is characterized by several changes in mood and tempo, a heavy reliance on the two main themes, and thick chordal writing for the piano soloist. The second movement, marked “Andante con moto,” is intimate with a significant number of solos performed by the flute, trumpet, oboe, and horn. Jazz influence is abundant here, recalling melodic gestures directly from his Rhapsody. After a robust cadenza and a lyrical middle section, the piece seems to gain in intensity, only to fade away. The hustling and driving third movement marked “Allegro agitato” contains seemingly endless repeated notes and great rhythmic vitality. Ending with a transformed and romanticized return of the original piano theme from the first movement, this concerto effectively combines elements of American popular styles with classical approaches to form and the piano concerto genre.

Gershwin’s original approach to musical composition in the early twentieth century was noted by many composers. Gershwin had a lifelong fascination with the music of Debussy and Ravel. He tried to study with Nadia Boulanger and Maurice Ravel, both of whom denied his request with Ravel famously saying “why become a second-rate Ravel when you’re already a first-rate Gershwin?”

Even Arnold Schoenberg, whose musical sound world seemed to be at total odds with Gershwin’s jazz-infused writing, noted the unique contributions of Gershwin’s style. Schoenberg eulogized Gershwin stating that he “was one of these rare kind of musicians to whom music is not a matter of more or less ability. Music, to him, was the air he breathed, the food which nourished him, the drink that refreshed him. Music was what made him feel and music was the feeling he expressed. Directness of this kind is given only to great men. And there is no doubt that he was a great composer. What he has achieved was not only to the benefit of a national American music but also a contribution to the music of the whole world. In this meaning I want to express the deepest grief for the deplorable loss to music. But may I mention that I lose also a friend whose amiable personality was very dear to me.”3

Want to listen to Gershwin’s Piano Concerto in F? Check out this recording from the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition 2022 with finalist Clayton Stephenson at the piano and Marin Alsop conducting the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra.

What he has achieved was not only to the benefit of a national American music but also a contribution to the music of the whole world.

Arnold Schoenberg on George Gershwin3

Sources

- Herbert Glass, “Concerto in F,” Program Notes, Los Angeles Philharmonic, laphil.com/musicdb/pieces/1441/concerto-in-f.

- Michael Thomas Roeder, A History of the Concerto (Portland, OR: Amadeus Press, 1994), 421.

- Martin Buzacott, “The Unexpected Friendship Between Gershwin and Schoenberg,” Classically Curious (blog), Australian Broadcasting Corporation, March 18, 2019, abc.net.au/classic/read-and-watch/music-reads/classically-curious-gershwin-schoenberg/10915460.