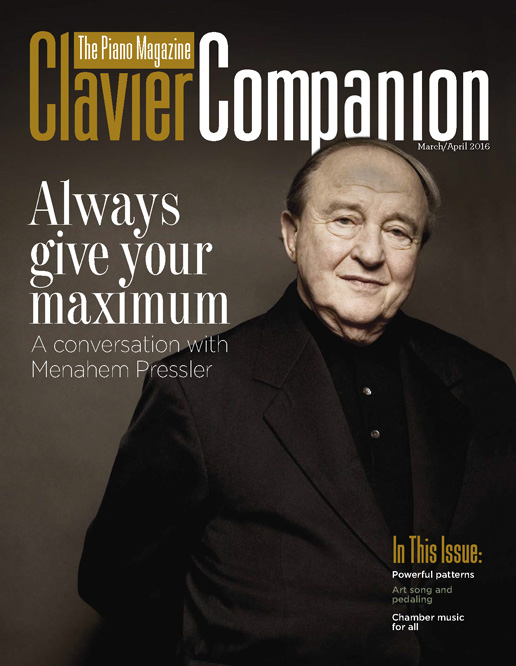

With deep sadness at the recent passing of Menahem Pressler and in greatest honor and memory of his legacy, we share this article by Jerry Wong as it originally appeared in the March 2016 issue of The Piano Magazine: Clavier Companion.

Menahem Pressler, best known as the pianist of the unparalleled Beaux Arts Trio for more than fifty years and a revered Distinguished Professor at Indiana University’s Jacob School of Music for even longer, continues a daunting schedule of performing and teaching. At age ninety-two, he shows no signs of slowing down, as plans for the future and the deepest devotion to his craft appear to drive his everyday existence.

I first met and played for Mr. Pressler in masterclasses at Biola University, in La Mirada, CA, in the late 1980s. His residencies there, consisting of a solo recital and classes (often two or three in a day) were an exercise in focused endurance, both for the performers and those attending. Students from all over southern California arrived with major staples of the repertoire, and Pressler, in one three-hour class after another, delved into each work with incredible insight and a disciplined approach to the composer’s intentions. Never showing fatigue, he gave his absolute best to each student. His style was demanding, attentive, and all-encompassing.

Playing for Pressler three years in a row during my teens eventually led to an audition at Indiana University. “You’ve played for me each year, and each year I see improvement,” he said, in a moment of quiet encouragement that remains blazed into my memory more than twenty-five years later. Working with Pressler in his studio in Bloomington, Indiana, was terrifyingly electric and powerfully illuminating. When my studies concluded, I often attended his concerts and masterclasses, but the recent opportunity to sit alone with him for over an hour and discuss his career, approach to teaching, and general reflections revealed new stories and ideas from this now iconic figure in the world of classical music.

I found Mr. Pressler on a sunny afternoon in early summer, sitting quietly in his daughter Edna’s condo in Boston, eagerly awaiting our conversation. His recuperation from a recent medical procedure had been strenuous, yet appeared to leave him unscarred and even refreshed. “I was with the doctor today for some tests, and the results were very good. I smell roses!” Beaming from ear to ear, he reminded me of the cat who caught the canary. And this cat has had nine lives for certain—not only in the real sense of his good fortune, but in the musical sense as well.

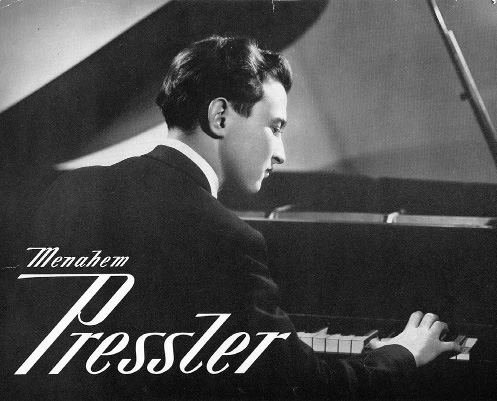

Born in Germany in the early 1920s, Pressler’s immediate family fled the Nazi regime to Palestine when he was just a boy. Extended family remained behind and perished in concentration camps. From the darkness of this early experience, a brighter theme of Pressler’s future emerged: an appreciation for his good fortune and a determination to make the life he had been spared meaningful. Music lessons became the highlight of his youth, and he ultimately opted to travel to San Francisco in 1946 to participate in the Debussy International Competition. A chance meeting in the basement of Steinway Hall in New York with famed pianist Byron Janis cast gloom over his first visit to the States. “Don’t go to the Debussy,” Janis warned, “the competition is fixed!” “the Pressler replied, “I must go. I promised everyone back home I would compete.” He went, won, made his debut with the Philadelphia Orchestra, and began a career as a solo pianist with significant engagements.

Early years

In the years that followed the Debussy prize, Pressler made his home in New York City, fulfilled his concert engagements, and continued to expand his musicianship by pursuing lessons with some of the most celebrated teachers of that era. Studies with Isabelle Vengerova (The Curtis Institute of Music), Robert Casadesus (Fontainebleau Music Festival), Egon Petri (masterclasses at Mills College) and finally Edward Steurmann (The Juilliard School) all formed significant impressions on the young soloist. From these influences, Pressler can trace his lineage back to Busoni, Leschetizky, and Schoenberg.

Aspiring pianists of today should note that Pressler’s life at this point was a delicate balance of performing and sporadic lessons. Real life lessons from the concert stage supplemented the work in the studios of these various masters and vice versa. “You live and you learn, and at the end, you still feel like a student,” Pressler mused. His studies were certainly eclectic: the strict Russian pedagogue Vengerova (teacher of Sidney Foster, Gary Grafmann, and Jacob Lateiner), the consummate French pianist Casadesus, and the Busoni prodigies Petri and Steurmann all seem to represent very different schools and training. Yet somehow, Pressler’s teaching and performing reflects a complete synthesis of all these different approaches. I can recall masterclasses in which he moved from Bach to Brahms and on to Berg with the same ease, the same exacting interpretive style, and, perhaps most of all, the same steadfast affection for each and every score.

When reflecting upon my own studies with Pressler, I mentioned the fact that each opportunity to peel away at a new composer or genre was equally invigorating. He never placed certain composers in an elite status over others. Smiling at my observation, he said: “Actually, I liked Liszt, but my wife never did! Yes, okay, she liked the B Minor Sonata and the Dante, but anything else, she said, ‘don’t practice this at home!’ She thought it was cheap, but I disagreed. And I teach Liszt to my students. I think he was an enormous composer with great beauty. I played the Rigoletto paraphrase many times. After you see and hear a Rigoletto in the opera hall, you know that Liszt ennobled the piano in the way that Verdi ennobled the stage.”

Beaux Art Trio

Much has been written and said over the years about the venerable Beaux Arts Trio. Since their debut at Tanglewood in 1955, the Beaux Arts Trio has toured worldwide and recorded virtually the entire trio literature, in addition to several collaborations with guest violists for quartets. While Pressler has remained a constant, the other members of the trio have changed over the years, beginning with violinist Daniel Guilet and continuing with Isidore Cohen, Ida Kavafian, Young Uck Kim, and ending with Daniel Hope. Original cellist Bernard Greenhouse was with the ensemble for thirty-two years, followed by Peter Wiley and Antônio Meneses.

Pressler is able to reflect upon all the various players in very fluid conversation. “You know that we recorded the Schubert Trios three times. Each time the change of membership brought some new life and meaning to the music.” He chuckled as he shared a spirited debate he had with Guilet and Greenhouse early in the trio’s history over the tempo of the Ravel Trio. “Why are you playing so slowly? What are you doing?” Followed by: “It’s how I feel this music.” And finally: “You feel differently from Ravel!” Growing serious for a moment, he remembered the late Greenhouse: “We were really very much together. As people, and musically, we were exceedingly close.”

Always one to remain more in the present, Pressler moved our conversation ahead to the closure of the ensemble. “Daniel was developing a huge solo career. He wanted to leave the trio. Our manager said to me: ‘Do you want to take another violinist? As long as you are in the trio….’ I stopped him. No. I would rather have the trio stop. I wanted the audiences to wonder—why did we stop? I didn’t want them to say that we should have stopped sooner!” The trio performed their final concerts in 2008.

On December 17, 2013, several generations of former Pressler students from all over the country converged on the Indiana University campus in Bloomington to enjoy a ninetieth birthday celebratory concert. His students have often made note of the fact that he shares the same birthday as Ludwig van Beethoven. For this event, however, Antonín Dvorák was the most significantly programmed composer. The Emerson Quartet joined Pressler for Dvorák’s popular Piano Quintet and Daniel Hope (former Beaux Arts Trio violinist) and David Finckel (cellist) joined Pressler for the “Dumky” Trio, a work heavily imbued with a tender sweetness that Pressler has brought to life literally hundreds of times on the concert stage. I called attention to the fact that Hope, the violinist whose exit symbolized the final chapter of the Beaux Arts Trio, joyfully returned to play with Pressler for this special event. Was there any whiff of regret about the younger violinist’s desire to pursue other avenues for his career? Pressler closed his eyes and with a quiet, peaceful affection, simply murmured: “Ah, Daniel, the one I love so much—he is a true sweetheart.”

New horizons

Late 2014 and early 2015 was a tumultuous time for Pressler. He was always known for keeping his priorities—performing, teaching, and family—all in a delicate balance without the slightest drama, but life caught up with him rather suddenly in a whirlwind of events. First, Sara Pressler, his beloved wife of fifty-five years passed away on December 19. Determined to honor his commitments, he traveled to Germany to perform Mozart’s A Major Concerto, K. 488, with the Berlin Philharmonic in a New Year’s Eve concert. “It was a special night,” Pressler recalled. “The orchestra sang like angels.” Immediately following his return to the States, however, he found himself hospitalized, first in Indianapolis and later in Boston, with what he now describes, in an interview with Dr. Virendra Patel of Massachusetts General Hospital on slippedisc.com, as “a time bomb within me.” The success of that procedure and his subsequent recovery is a testament to modern science, as well as the willful tenacity of a man in his early nineties, still full of life and music. Of all these events, Pressler spoke with the calm wisdom of a man who has weathered many storms: “Oh yes, indeed, all that happened in a short amount of time.”

As always, Pressler was most interested in discussing his plans for the future. Though he wistfully explained that his health issues had caused him to give up the cherished opportunity to serve on the jury of the Fifteenth International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow, the upcoming summer months were going to be as full as ever. A Wigmore Hall recital with baritone Matthias Goerne featuring works of Robert Schumann was the first engagement. With only two days of rehearsals scheduled before the concert, Pressler was eager to share his thoughts about this highly poetic and deeply personal repertoire. “Bring me the music from the piano,” he said. Flipping through the score with a quiet reverence, he began to consider tempi and expressive markings in the score. He pointed out interesting modulations, cross rhythms, and hemiolas, and eventually ended by lovingly humming the opening to Dichterliebe.

It is remarkable that in his late eighties and early nineties Pressler has turned his attention to collaboration in the lieder repertoire. Recitals with Christoph Pregardien in Schubert’s Die Winterreise and Heidi Grant Murphy in Schumann have been particular highlights of this relatively newfound interest. When questioning him about his many decades of trio, quartet, and quintet collaborations with the world’s finest string players compared to the current work with singers, he said: “With my string colleagues, I got to know how everything worked. I knew their fingerings and their bowings—and could even offer suggestions to them. But each singer breathes and shapes the line so individually, so personally—it is wonderfully unique.”

The teacher needs to make strong demand, while always knowing the potential of what each individual student can achieve.

Menahem Pressler

Alongside collaborations with singers, Pressler has had an increase of solo recitals and concerto appearances since the end of the Beaux Arts Trio. The previously mentioned Berlin Philharmonic performance was a return engagement, following his debut with the famed ensemble the pervious year. Amused again by his good fortune, he recalled a solo recital in Paris shortly after the Trio’s last concert. “Much to my surprise a critic asked: ‘why didn’t he stop playing with the trio earlier?’ Soon after that my manager called me. ‘Mitsuko Uchida is sick. She cannot play a recital in Vienna. Would you consider jumping in for her?’ And I said yes.” On short notice, Pressler played an all-Schubert recital. Once again the press that followed was glowing and again he reiterated: “really, truly, no one was more surprised than me!”

Though his programming often draws on repertoire by Beethoven, Schubert, Chopin, and Debussy that he has performed for many years, Pressler eagerly told me that he was planning to open some upcoming concerts with Mozart’s haunting A Minor Rondo. “As a youth, I asked my teacher for it and he said, ‘You are too young.’ Later, I worked with Steurmann. I asked for it again. He said, ‘You are too young for it.’ Then I served on a competition jury with Horzowski. Competitors had the option to select that Rondo. He said, ‘You know, whoever chooses the Rondo won’t pass to the next round.’ And, true enough, everyone who selected the Rondo was eliminated. But, when I became eighty, I decided that no one is going to tell me I’m too young for it. I’m going to try my very best.”

When reflecting upon my own studies with Pressler, I mentioned the fact that each opportunity to peel away at a new composer or genre was equally invigorating.

Jerry Wong

Teaching

“Give your maximum to each and every student. Require the maximum from them, but at the same time be sure they never feel that you do not believe in them.” When asking Pressler about his teaching philosophy, this was the first of a long string of almost proverb-like statements that transcended piano playing to the teaching of almost any discipline, craft, or subject matter. “The teacher needs to make strong demands, while always knowing the potential of what each individual student can achieve.” Most former Pressler students can attest to memories of what we might call “tough love.” In William Brown’s Menahem Pressler: Artistry in Piano Teaching, an entire chapter is devoted to Pressler’s humor. One citation after another describes Pressler’s witty manner of teasing a student for poor tone color or an unconvincing interpretation. In conversation, though, Pressler warned of truly abusive teaching. “I once knew of a famous teacher who said: ‘Why should I show this to you? You’ll never be able to do it.’ You say that to a student and they will never recover from it. It’s a kind of critique that doesn’t lead anywhere. It doesn’t help the student. Maybe it’s good for the ego of the teacher, but in reality, a great teacher develops a trust with the student that encourages the student to fight for knowledge and get better, and better, and better.” He smiled at me: “You know this now as a teacher yourself. Some students will play more and some students will play less. You as the teacher should be clear about what wonderful things each student is capable of attaining.”

Pressler is a firm believer in a variety of different finger exercises by Johannes Brahms, Charles-Louis Hanon, and Isidor Phillip. He advocates for them as a warm-up, as well as a means of developing a greater physical vocabulary at the instrument. “I still believe firmly in the exercises. I give them to my students when we are starting from the beginning. I do them myself. They strengthen my technique and still help me.” Gazing downward at his hands and then lifting them fluidly into the air, he said: “they help me create my own hands and fingers.”

As a juror of such prestigious competitions as the Van Cliburn and Queen Elisabeth, Pressler knows this particular phenomenon all too well. He maintains a positive and completely informed attitude about competitions: “I encourage students to enter, but to be aware of how fickle juries are and how unexpected the decisions can end up being. Jurors often have a limited view of how particular repertoire should or should not sound. If a student wins, great. If they don’t win but played well, it’s also just as great.”

When visiting Bloomington for Pressler’s ninetieth birthday concert, various faculty members expressed awe at his devotion to his teaching. His ability to stay long hours at school and work with his entire class in two days before resuming concerts tours has not withered. “My studio is as strong as ever,” he told me. “I have a wonderful class.” I asked if the students had changed much over his many years at Indiana University. He acknowledged that while the playing level is as high as ever, there is the occasional tendency to focus on too narrow a repertoire or skill set. “Sometimes teachers who want to send their students to an outstanding music school like Indiana don’t take enough care for the fundamentals—the foundation, so to speak, of the pianistic development. They teach them a piece or some pieces and say ‘with this particular repertoire you can get in.’ But it can’t be just that piece. It has to be something fundamental that you give the student which will stay with them in a variety of styles.”

As our conversation reluctantly drew to a conclusion, I begged Mr. Pressler for a few words of wisdom for how to gauge longevity in such a demanding career. Echoing the laments of so many friends and colleagues in the piano teaching profession regarding juggling practicing alongside student demands, I asked him how he had kept everything going for so long. He remembered his late wife Sara and expressed gratitude for her presence in the teaching studio over the years. “She was like a mother to my students. She was a strong part of the upbringing of the students and helped with the day-to-day scheduling. My wife was a magnificent coach who knew how to encourage the students. It was a special gift.” These days he enjoys input and companionship from his daughter Edna and also appreciates the many friends he has made all over the world who happily support and encourage him in his endeavors. He concluded: “In the end, really for me, the beauty of music has given a reason for my life.”